A cluster of historic bridges in the locality of Knocknagoshel hold a supply of tales of times past. Headley’s Bridge, which stands almost adjacent to Talbot’s Bridge, recalls the days of Lord Headley, who in 1824, ‘assisted by Mr Griffith, the Government Engineer,’ laid the first stone of the bridge ‘on the new line of road between Castle Island and Abbeyfeal’.

A report of the ceremony mentioned nearby Wellesley Bridge across the river Feale, so named ‘in honour of our patriotic and highly respectable Lord Lieutenant’.

A flood of the river Owveg in August 1880 caused great destruction to crops of ‘champion potatoes’ and mangolds but also to Bateman’s Bridge, another in the locality:

The scene of destruction took place at Drumaddamore, near Darby Cotter’s residence, part of the Hurly Estate and for years previous known to be a quaking bog … the Oubeg is a tributary of the Feale and was most accommodating as regards bridges, but now the village of Knocknagoshel is completely isolated as the two bridges that lead to it, Talbot’s bridge and Bateman’s bridge, are completely swept off.

A very different scene of destruction took place near Talbot’s Bridge on 6 March 1923. In her novel, 1921 (2001), Morgan Llywelyn gives this account of what occurred:

A letter in the handwriting of a known local informer had been delivered the evening before … the letter gave the location of a major IRA weapons dump at Barranarig Wood, Knocknagoshel … the letter was a forgery. A mine casing packed with shrapnel and an explosive charge was waiting, buried in a lonely field at the supposed dump site. At two am on March sixth, five members of the Free State Army – three officers of the Dublin Guard and two enlisted men – were blown apart.

A contemporary press report named those killed:

Three officers and three volunteers of the Free State Army were blown to pieces in an explosion of a trap mine concealed in a dump near Knocknagoshel, East Kerry. The dead officers are Captain Michael Dunne and Captain Joseph Stapleton, both of Dublin, and Lieut O’Connor of Castleisland. General O’Daly, of the Derry Command, has issued an order that mines and dumps must in future be removed by rebel prisoners.

Order enforced with frightening rapidity

Michael’s research papers show that General O’Daly’s order was enforced with frightening rapidity: ‘Paddy O’Daly, like a raving lunatic at the loss of his former Dublin Guard comrades – decided to take revenge’. Michael followed events of the 24 hour period from 2 am on 6 March 1923 to 2 am on 7 March 1923.

His notes include the bomb plan at Talbot’s Bridge, Barranarrig (including the assembly of the bomb, its concealment, names of those involved, names of those killed) and its repercussions.

In Tragedies of Kerry, a book documenting this period of the Civil War in Kerry, author Dorothy Macardle suggested that eight prisoners at Tralee, four at Killarney and five at Cahirciveen ‘were reprisals for the Knocknagoshel mine’. She described how nine men were taken from the barracks in Tralee in the early hours of 7th March to Ballyseedy Wood ‘to remove barricades’. The ‘barricade’ was a log, against which was placed a mine. Dorothy Macardle described what happened next:

The soldiers had strong ropes and electric cord. Each prisoner’s hands were tied behind him, then his arms were tied above the elbow to those of the men on either side of him. Their feet were bound together above the ankles and their legs were bound together above the knees. Then a strong rope was passed round the nine and the soldiers moved away.

Miraculous survivor

Miraculously one of the nine, Stephen Fuller of Kilflynn, survived the explosion which threw him, almost unscathed, onto the road. He took refuge in a ditch and then made his escape. Notes on his immediate movements are found in Michael’s papers:

Kitty Curran – her mother let him in. Next morning Johnny Connor brought him to Con Billy Daly’s Knockane … moved from Knockane to Boyles, Protestants of Glenageenty.

Stephen Fuller later gave an account of his escape:

I crashed through shrubbery until I met the river which I got into up to my waist. When I got to the bank I made for a bunch of trees on the side of a hill … I ran until I met another fence and met the gable of a house. The house was Currans at Hanlon’s Cross.

Eight killed

The dead were named in a contemporary news report as John Daly, Woodview, Castleisland; Patrick Hartnett, Listowel; Patrick Buckley, Scartaglen; James Walsh, Lisodigne, Tralee; George Shea, Lixnaw; T[imothy] Tuomey, Lixnaw; John O’Connor, West Terrace, Liverpool; Michael O’Connell, Fahaduv, Castleisland.

Michael notes affirm this, and enlarge on the Intelligence Officer, Commandant David Neligan’s selection of the nine men, and names of others involved.1

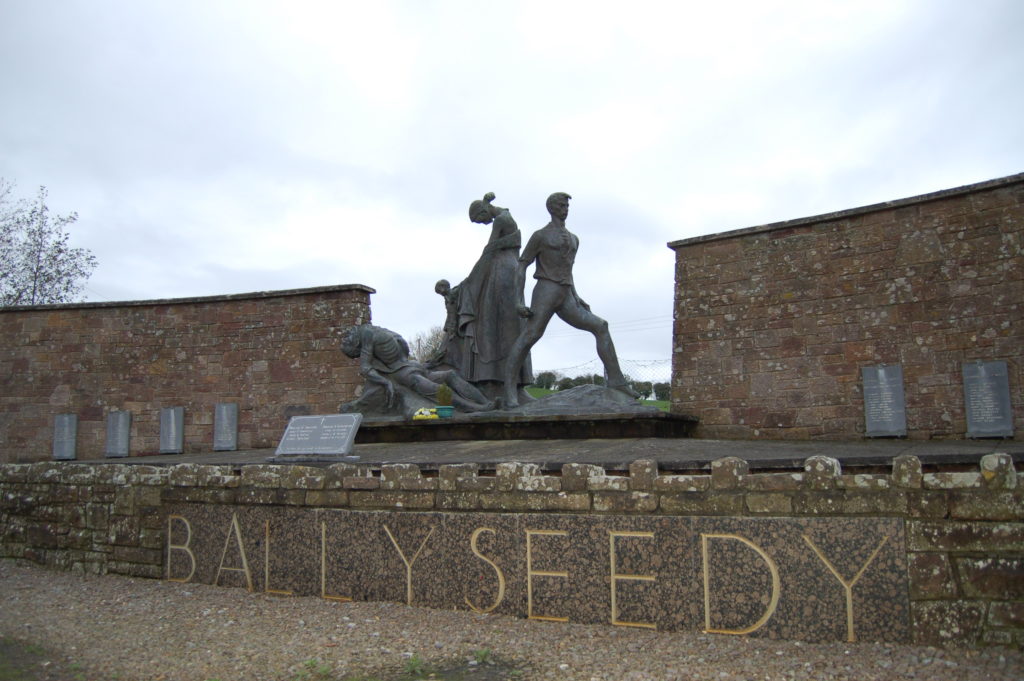

The miraculous survivor of the episode, former TD Stephen Fuller, died at Edenburn nursing home in February 1984. In March 2014, a special function at Ballyseedy, organised by his son, allowed relatives of the nine families to meet for the first time.2

A ceremony also took place at Knocknagoshel some months before (November 2013) when a monument to the memory of those who died near Talbot’s Bridge in 1923 was unveiled by Jimmy Deenihan, TD.

Memorial at Talbot’s Bridge. The monument was vandalised in early 2014

A later casualty of the 1923 affair, blacksmith Daniel Murphy of Knocknagoshel, also figures in Michael’s notes. Daniel Murphy, shot in ‘Baranarrig ancient wood’, is remembered in the song, The Blacksmith Volunteer:

Twenty bullets pierced his heart God help his mother dear, He lived and died for Ireland, the Blacksmith Volunteer3

There can be no doubt that Michael found this a joyless record to put together, but the historian in him recognised it as one which could not be swept under the carpet.

___________________

1 Commandant David Neligan (1899-1983). His memoir, The Spy in the Castle was published in 1968. 2 A wooden memorial cross was erected near the gates of Ballyseede Castle in 1959. The Ballyseedy monument, on the main Tralee road, is described in 'Yann – Renard Goulet: sculptor of the Ballyseedy Memorial'. It was written by Michael Kenny (1956-2011), founder member of the Patrick O'Keeffe Musical Festival in Castleisland (and co-founder of the Castleisland Cultural and Heritage society) and published in The Kerry Magazine (2010), No 20, pp22-23. 3 The song is held in The Schools’ Collection, Cnoc Breac School (roll number 13041) Volume 0450, Pp 237-239 (song attributed to Tadgh McGovern) and Tuairin Ard School, Volume 0450, Pp 33-34 (song attributed to Tadgh Barnett). Barranarig (Barranarrig) is recorded as a townland in the Tithe Applotment records (Baranorig Lower, Middle and Upper).