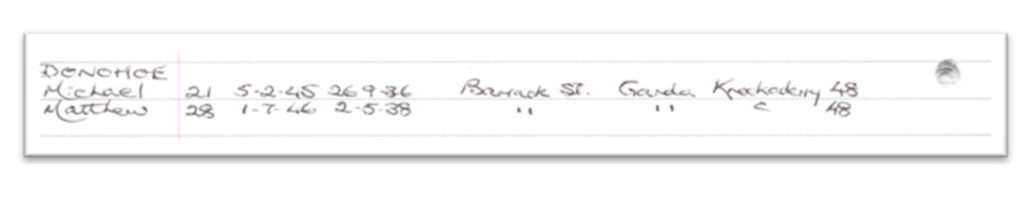

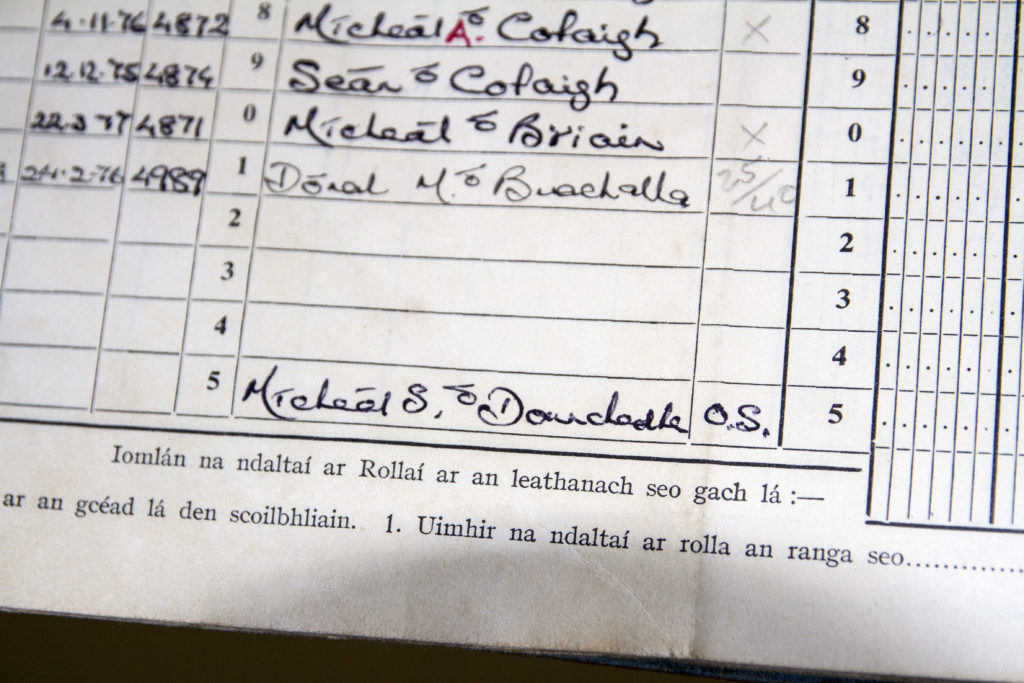

Michael O’Donohoe’s transcription of the roll book of Castleisland Boys’ National School contains his own enrolment there in 1945:

This followed the appointment of his father Matt, a garda based in Farranfore, to the station in Castleisland. From this time on, the town was home to the O’Donohoe family.

The roll book, which consists of 72 handwritten pages covering the period 1875 to 1958, includes a useful index. Michael studied at the school for four or five years before he earned a scholarship to the Good Counsel College, New Ross, Co Wexford. He subsequently graduated from St Patrick’s Training College, Drumcondra as a national school teacher.

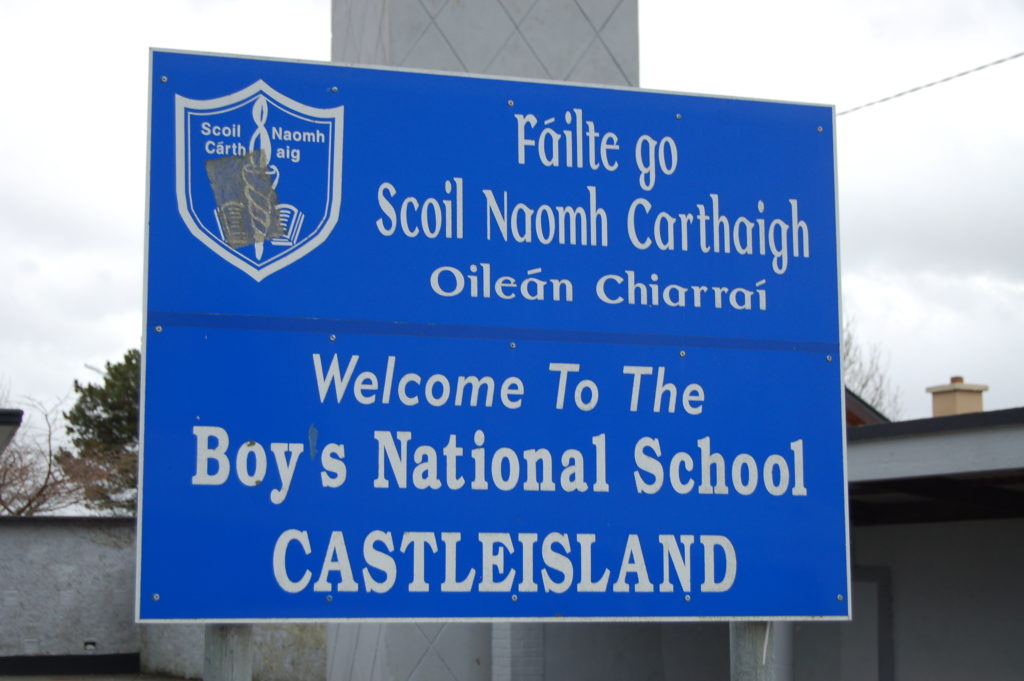

Michael returned to Castleisland in 1956 to take up a post at his former national school, one he would hold for 35 years.

School History

The history of the boys’ national school in Castleisland can be traced through Michael’s career. The school where Michael was educated and at which he first taught was situated in the former Fever Hospital in College Road. A new school was built on the same road and opened in 1961 (St Carthage) and there Michael taught until his retirement in 1991. The school celebrated its fiftieth year in 2011.

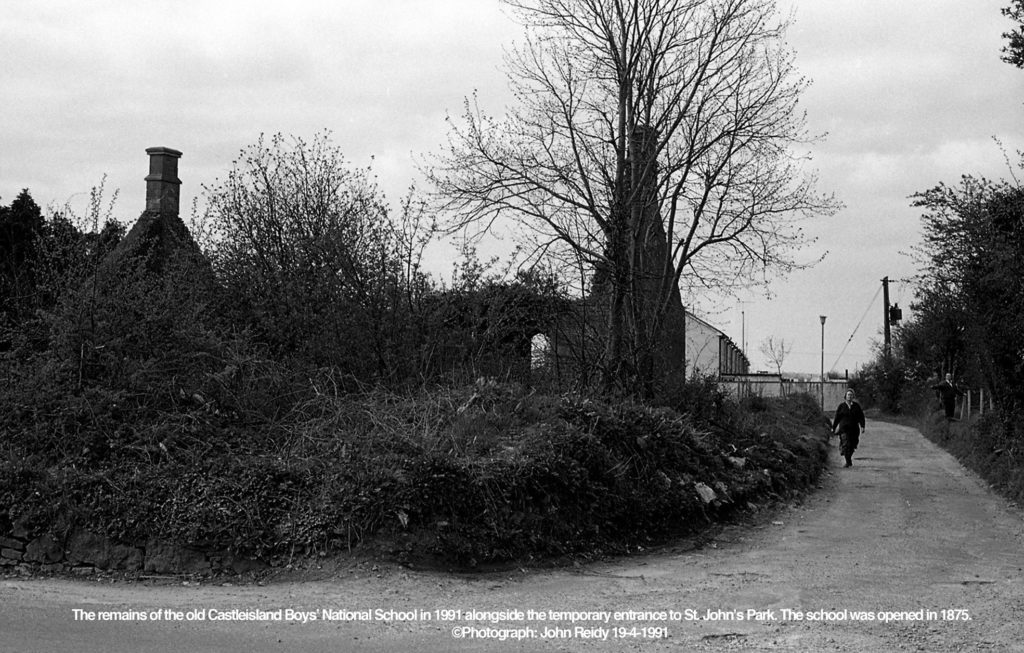

The old ‘Fever Hospital’ school is now St Patrick’s Secondary School. Schooling in that building began in 1930 after the existing national school, built in 1875 and situated at Bawnluskaha on the Limerick Road, was condemned.

Nothing, save remnants of an outside wall, remains of this Victorian building which was demolished in the 1990s.

Many schools have disappeared in like manner in recent years, taking with them unfathomable tales.

National Schools in Kerry

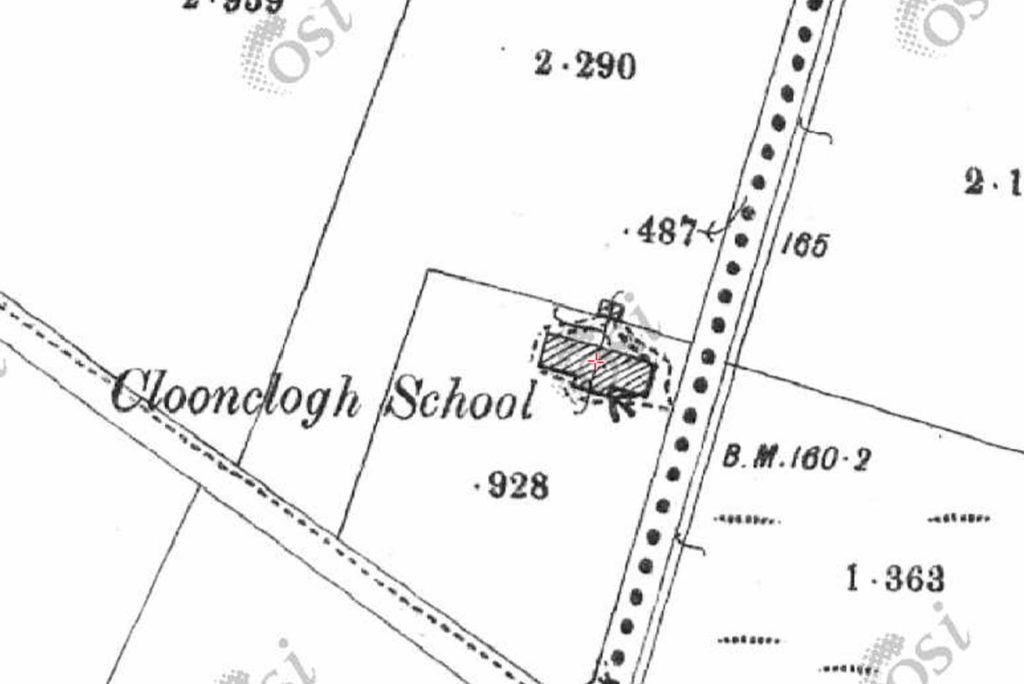

Some stories, however, come down to us, like the robbery at Cloonclogh national school in Currow in 1864. The school, built in 1854 (and of which nothing remains) was entered in the dead of night, the master’s desk smashed and its contents made off with. The patron of the school, Rev James Scanlan, offered a reward of £2 for information on the intruders, a sum matched by the locals.

Victorian-style discipline

A fine of £2 was handed out to a school teacher of Castleisland National School in 1874 for ill-treating a 12 year old boy. A description of the offence was given in court:

He made the poor creature kneel upon his bare knees on the ground with his arms extended and a slate in each hand, and the moment he let his hands clasp he was struck with a rod across the arms. The Head-constable said he saw the child the next day and his arms and body were covered with welts. He had seen soldiers after being flogged, and they were not in a worse state.1

In 1888, a Co Clare school teacher named Patrick Robinson and his daughter (a monitoress) were shot in Lackbrooder School, some miles distant from Castleisland, while teaching class. The shooting, carried out by three armed men, occurred in front of 40 students. Robinson was forced to his knees and asked to swear he was ‘not to be speaking about his neighbours’ (giving information to the police). Two of his daughters were brought out of the class and forced to kneel down with their father. Robinson was then shot in the stomach and the men fled.2

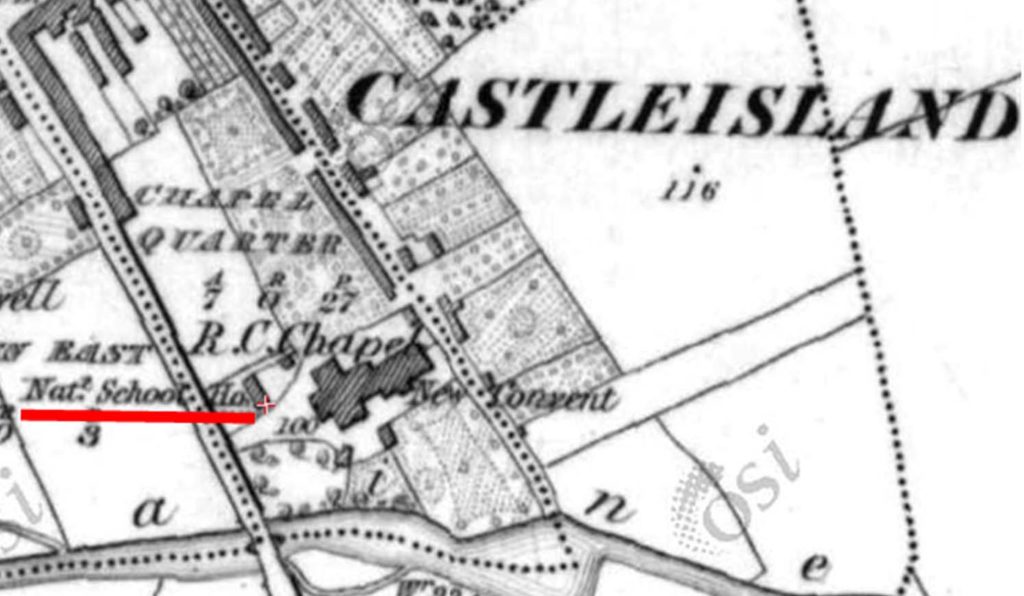

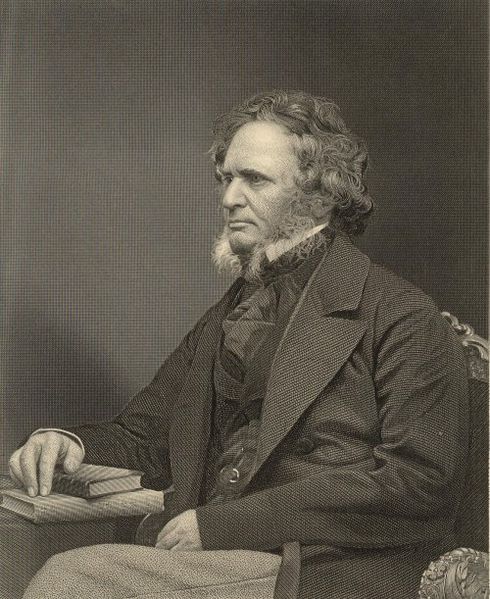

The first national school in the parish opened at Knockatee in 1834, Maurice Stack was teacher in charge.3 Castleisland National School – long since demolished and forgotten – opened at chapel quarter in 1844 under Lord Stanley’s multi-denominational primary education system of 1831.

Lord Stanley, known as the father of national education in Ireland, established a board and put building funds in place. Applications began immediately: there were 789 schools up and running in Ireland by 1833.4

Castleisland numbered among the earliest schools in Kerry. The national schools were not entirely trusted by the Roman Catholic population. At Listowel a rumour went out that the children attending the national schools were to be branded with the letters V.R. by order of the government. The rumour gained ground and anxious parents rushed to the school and took their children away.

Store of History in Registers

There is a store of history in the schools. Michael’s registers are invaluable not alone for those with an interest in Castleisland national school – the archive also contains records of the convent schools in Castleisland (girls and boys) and the roll book of Glountane National School, which includes of course, the name of its famous student, Patrick O’Keeffe.

Michael used the content of the school records to create, in a separate project, a number of booklets relating to residential areas of the town of Castleisland such as Barrack Lane, Bridewell Lane and Hospital Road.

His interest in the town, its inhabitants, its history is evident in his articulate, painstaking transcription of valuable school records.

The Castleisland Boys’ National School roll book can be read here.

_________________________________

1 ‘With respect to the charge against a teacher of the Castleisland National Schools for cruelly ill-treating one of his scholars and lest it should be supposed that Mr Daniel Desmond (head-teacher of the Castleisland adult school for many years) is the party alluded in the report, we wish it to be distinctly understood that it is a subordinate teacher of the same schools that was fined for the offence’ (Kerry Evening Post, 19 September 1874). 2 ‘The scene in the room after they left is almost impossible to describe’. Robinson, who was married to a local woman named Margaret Horan and who had lived in the area for 30 or more years, was removed to his residence, which adjoined the school, and Dr Harold arrived to give medical assistance. He found ‘no less than 70 shot holes in the trousers’. Robinson was later conveyed to Castleisland Hospital. Patrick Robinson, a father of 13, survived and he died in 1918 (his widow died in 1938). He was a school teacher and a poet, his popular verse of ‘outstanding merit’. His verse can be read in The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0450, pp174-177. The school, invariably described as Coolnagert, Lackfoodas, Lackvoodre, Knockafoodra and Knocknagoshel, was situated about midway between Castleisland and Abbeyfeale close to a constabulary hut. It was suggested the school master was shot because one of his daughters may have been intimately involved with an officer there (ref: Cork Constitution , 14 March 1888 and Weekly Irish Times, 17 March 1888). The Schools’ Collection relates a tale of how the townland acquired its name. A well known man named Bruadar, reputedly rich, went rambling in the district and attracted the attention of robbers, who murdered him. At that time ‘people always remembered a person who did not die a natural death. They had a custom of throwing a stone on the spot where a person was killed whenever they passed that place.’ In time, a memorial heap of stones in honour of Bruadar marked the murder spot which the people called a leacc. From that time the place was called Leacc Bruadair, the correct name of the townland, ‘not logfuidder which has no meaning’. English forms of the name are Loughfouder and Laughtfouder (School: Leachtbhruadair / Loughfooder / Lackbrooder, The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0450, pp109-110). Further reference, Loughfouder National Schools – Through the Generations (1850-2016). 3 Castleisland Church and People (1981) by Fr Kieran O’Shea, p55. 4 Lord Stanley's son, Edward Henry (1826-1893) would later campaign for the establishment of public libraries.