Twiss says that time will prove his innocence and

he forgives those who swore falsely against him.

Telegram from Patrick H Meade, the Mayor of Cork, to the press1

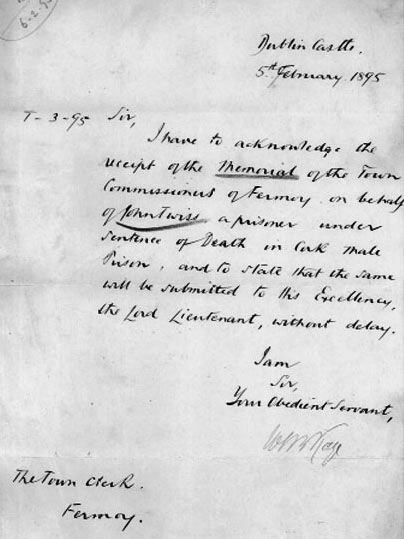

An interesting document has recently been added to the Michael O’Donohoe Memorial Heritage Project.2 It is a nineteenth century letter handwritten in ink sent from Dublin Castle to the Town Clerk of Fermoy to acknowledge receipt of a signed petition to reprieve the condemned John Twiss from his sentence of death. The date on the letter is 5 February 1895, just four days before Twiss was hanged in Cork County Jail. 3

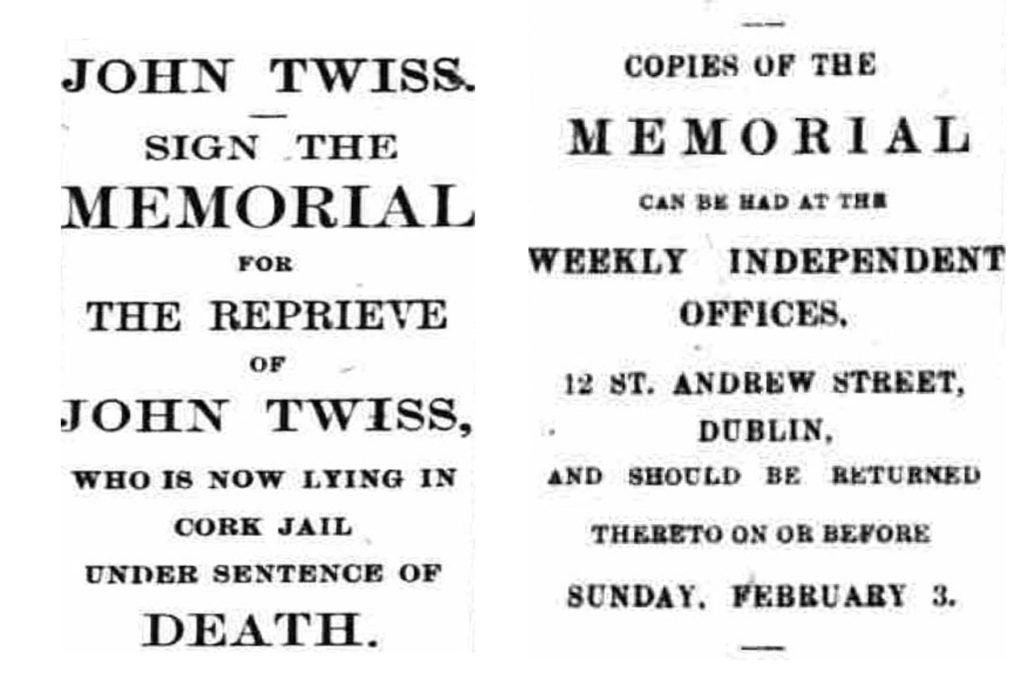

The memorial, which was presented to Sir David Harrel, Under-Secretary to Lord Houghton, the Lord Lieutenant, on Monday 4 February, was signed by almost 40,000 people consisting of members of Parliament, clergymen of all denominations, magistrates, members of public bodies (including Cork Corporation, the Fermoy Town Commissioners and the Mallow Town Commissioners) and representative men and persons of all creeds and classes.

The signatures were enumerated as follows:

8,000 Mayor of Cork

1,775 Parts of Cork and Kerry (per Fitzgibbon, solicitor for Twiss)

14,612 Weekly Independent memorial Dublin City

13,356 Provinces

916 Manchester, Edinburgh and Liverpool

Total 38,6594

Many more signatures were submitted in the hours and days that followed:

The signatures now exceed forty thousand names. In addition to those lodged at the Castle on Monday morning a further batch in the afternoon were sent to the Under Secretary … Last night an additional number of memorials were also posted to the Irish Office.5

The points set out in the memorial were as follows:

1 That the evidence against the prisoner is contradictory, circumstantial and unreliable and in the case of the unsworn witness, Donovan, open to doubt.6

2 That one of the Crown witnesses is notoriously a criminal character.

3 That no evidence was given against the prisoner solely in the interests of justice but the entire testimony was procured through personal motives.

4 That in a district where it is notorious that conviction was already secured through perjury, and the perjurers avoided legal prosecution, a reward such as was offered by Lord Cork in the present case was a direct incentive to the manufacture of evidences.7

5 That the strongest evidences given against John Twiss presuming that it was absolutely reliable proves that he was guilty of no overtones in the commission of the crime. That this is a consideration upon which the prerogative of mercy has already been exercised.

6 That the evidence of his being at Glenlara at all was purely circumstantial with the exception of the testimony of the little boy, John Donovan, who admittedly identified another man named Michael Corcoran as one of the men who killed his father; and though Twiss was present at the time of this identification, he failed to pick him out and only identified him some days after when placed between two policemen.

7 That the evidence of Lyons and his wife, who identified Twiss as one of the men they saw on the horse on the night of the murder going in the direction of Glenlara, is not reliable, having regard to their unfriendly relations with Twiss, and the large reward offered by Lord Cork to anybody whose evidence would lead to the conviction of the murderers. These witnesses admitted on cross-examination they perjured themselves, and supplemented to a large extent the evidence given before the Petty Sessions Court.

8 That the evidence of Brosnan was unworthy of belief owing to his character and to the contradiction of his sworn statement that he and the prisoner Twiss were not during the 20th April together under the archway in Castleisland with Constable M’Lony; that the evidence of the Crown as to the minute particles of blood alleged to have been found on Twiss’s shirt afford no support to the belief that Twiss was engaged in the murder; on the other hand, the Crown failed to show that blood, if found on the prisoner’s shirt, was human blood, and in a case like the present no importance whatever ought to be attached to this part of the case.

9 That since the date of the trial and conviction of Twiss, certain statements have been made which necessitate close inquiry in order to ensure that no miscarriage of justice shall take place; for instance (a) the statement by Brosnan to Mr D M’Donnell of Killarney that Twiss had nothing to do with the murder of Donovan (b) the statement made by Twiss himself that he had been offered money to give evidence against others (c) the statement made by Mr William Hennessy of 60 Clarence Street Cork that three of the jurors who tried Twiss were related to the murdered man, Donovan; and other statements.8

The time and effort expended in the campaign to save Twiss from the gallows amounted to a powerful show of hands. However, it was all in vain. On Thursday 7 February in the House of Commons, the matter of Twiss was rapidly dealt with by John Morley, Chief Secretary for Ireland, during the business of the day:

Ministers were found struggling with their first list of questions. There were 78 on the printed paper and, roughly speaking, those figures were doubled. They were all dealt with rapidly, however, for they were over before 5 o’clock. The Irish questions were numerous and important, some of them dangerous, but Mr Morley replied to them with the greatest good humour and geniality. Even when he announced that the murderer Twiss is to be hanged in due course not the least protest was raised.9

Michael Austin Manning (1858-1908), founding editor of Dublin’s Irish Weekly Independent, had the news confirmed by letter from Dublin Castle on 7 February:

Sir – With reference to the memorials handed to me by you on the 4th instant, and to your letters of that date and 6th instant, forwarding further lists of names to be added to the memorials on behalf of John Twiss, a prisoner under sentence of death in Cork Male Prison, I am directed by the Lord Lieutenant to acquaint you, for the information of the memorialists, that on a full consideration of all the circumstances of the case his Excellency has felt it to be his painful duty to decide that the law must take its course. I am, Sir, your obedient servant, D Harrel.

The mark of Cain is on the forehead

of all who brought Twiss to his doom10

The decision was not well received in Ireland. One writer described it as ‘a triumph for Morleyism’:

By this time tomorrow Mr Morley can point to a corpse lying in unhallowed clay as evidence of his success as a ruler.

The writer added, ‘We are reminded of the Maamtrasna case of Myles Joyce, who was hanged by Earl Spencer under circumstances that sent a shock of horror and indignation through the community … But Myles Joyce was innocent; the real criminal lives and is well known to the authorities.’11

Another writer stated, ‘We do not think it is possible in any other country than Ireland that representations for a reprieve so numerously and influentially signed would have been thus disregarded’.12

Morley was accused of having no backbone:

The official who is never tired of boasting of the peace which he has brought about in Ireland has not the courage to grant a reprieve in the case of the one man sentenced to death for an agrarian crime since he entered into office.13

The Twiss Reprieve Committee, consisting of representatives from the several trades and other societies of the city of Cork, sent a telegram to John Morley to the effect he was held primarily responsible for a gross miscarriage of justice.

Twiss meets his fate

Mr Andrews, the Governor of Cork jail, announced the news to Twiss, who displayed great concern about the welfare of his sister, and occasionally burst into tears.14

Twiss had little time left to reflect on his situation. On Saturday 9 February 1895 he was hanged in Cork prison for a murder that, in all probability, he did not commit.

Earlier this year, the case of Twiss was investigated by modern standards in the BBC documentary, Murder Mystery and my Family. To the joy and relief of Twiss’s descendants, senior Crown Court Judge David Radford concluded that Twiss’s trial ‘was not properly based on evidence which could lead to a safe conviction’.

A posthumous pardon – maithiúnais –was signed earlier this year for Myles Joyce. A similar arrangement for Twiss might not be out of place.

___________

1 Evening Herald, 8 February 1895 2 The document, IE MOD/C20, was kindly donated to the collection by Daniel Paul Stimpert who purchased it at auction. 3 Dublin Castle assured the Town Clerk that the memorial would be forwarded to Lord Houghton, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, ‘without delay’. Lord Houghton was Robert Crewe-Milnes, 1st Marquess of Crewe (1858-1945). 4 Kerry News, 8 February 1895. 5 Evening Herald, 7 February 1895. 6 The text of the Cork Petition to reprieve John Twiss included a little more information: 1. That there was no evidence that Twiss, though alleged to have been present at the scene of the murder, committed any act of violence on the deceased or took any active part in the murder; on the contrary that he is reported to have said to the actual perpetrator, ‘Come away, Jack, you have done enough’ which would go to show that if present at the worst, he only intended to inflict a beating on the unfortunate man and not to deprive him of his life. The allusion to ‘Jack’ was contained in the following report of the murder of James Donovan, a man in the employment of the Property Defence Association: ‘John Donovan of Glenlara, a young lad of about seven years of age, was put forward. Having satisfied the Bench that he understood the nature of an oath, he was sworn … James Donovan was his father; his father was dead; he remembered the night that he was beaten; his father went to bed about five o’clock that night … he did not go to bed for about an hour after his father … he went inside his father in the bed; there was a lamp burning in the room, hanging on the wall, when he went to bed; the lamp was lighting when he went to bed; he was awakened by hearing the window breaking; he then heard someone pelting the door; the door then opened and two people came into the house; when the two men came into the room one of them struck his father who was in bed at the time; that man struck his father on the head with a gun; the other man then said, ‘Come away Jack; you have enough done to him’ … the man who struck him with the gun then dragged him out; they then shot his father with the gun in the yard; he heard two shots; his father came back into bed again and the men didn’t come in anymore; his father had only his wrapper on when they dragged him out into the yard; when he came back to bed he was bleeding from the head; the lamp was lighting all the time; one of the men was like the fellow who used to give him a riding; that was the man who had the gun … Witness was then asked if he could identify the man if he saw him again and said he could, pointing to the man, Eugene Keeffe’ (Kerry Evening Post, 16 May 1894). Fitzgibbon, solicitor for Twiss, stated, ‘The whole fabric of the case rested on the evidence of the young boy Donovan as to the identification of the prisoners. They were at a particular and a terrible disadvantage. They would be kept immured in prison during the long winter months and when that boy again came before them he would be nearly a year older, besides being well trained and educated in the meantime … it would be a monstrous injustice if those young men were to be kept in prison while it suited the Crown to be searching all the fairs in Munster in search of tramps and jail birds to bolster up the case which rested solely on the corner stone of that young fellow’s evidence’ (Cork Constitution, 16 July 1894). Eugene Keeffe was tried in Cork on 6 December 1894 and Arthur Hackett, on behalf of Keeffe, accused the police of manufacturing evidence. The Crown described the weight of evidence against the prisoner as ‘overwhelming’ and if a jury could not be satisfied of Keeffe’s guilt, they opined, then they knew not ‘how those charged with the preservation of the peace of the country could bring home guilt to criminals’. Eugene Keeffe was found not guilty and discharged (‘Acquittal of Keeffe, Freeman’s Journal, 8 December 1894. Full report of trial in Cork Constitution, 7 December 1894). 7 The following deposition serves as illustration of nineteenth century justice in Ireland when witness statements could be bought. A man named Patrick Reidy of Castleisland protested, in a letter to the editor, about his involvement in the Twiss case. He denied making a statement against Twiss and that on fair day in Castleisland, ‘all that he had said was that he heard a sergeant say he arrested the wrong man when he arrested Twiss’ (Letter to the Editor of Cork Evening Echo reprinted in Cork Constitution, 7 February 1895). Reidy’s deposition, however, submitted to the editor of the Cork Examiner by the Mayor of Cork, showed otherwise. The deposition had evidently been made before Charles E B Mayne, Resident Magistrate, on 26 November 1894. The Mayor of Cork stated that Reidy was an inmate of the Union Hospital in Tralee on the fair day alluded to in his deposition, and had been for some time. Deposition of a Witness The Queen v Eugene Keeffe and John Twiss – The deposition of Patrick Reidy of Castleisland in the County of Kerry, labourer, taken in the presence and hearing of said defendants, who stand charged that on the 21st of April 1894 in the County of Cork, they did feloniously, wilfully and of their malice aforethought kill and murder one James Donovan. The said deponent saith on his oath – I am a labourer, living in the town of Castleisland. I remember the fair held in the town, that was a few days before John Twiss, the prisoner now present, was arrested. I was at that time in the employment of Mrs Milward, of Bellyegan. I went to the fair early in the morning with sheep, the property of Mrs Milward to sell. I sold the sheep and I remained in the town during the day and until night. I remember during the day going up to MacElligot’s public house. On my way there I saw Twiss, the prisoner, standing on the footpath. He was talking to another man who was a stranger to me, he was talking loudly. He said to the strange man, ‘Did you hear that your neighbour was going to be shot?’ ‘What neighbour,’ asked the strange man, ‘Yes, Donovan’ said the strange man, ‘Yes’ said Twiss, ‘that damned emergency-man’, ‘Are you going there,’ asked the strange man. Twiss replied, saying, he did not know. That was all the conversation I heard as I then passed away. Twiss was not drunk. In some days after I heard of Donovan’s murder.(full report, Cork Examiner, 8 February 1895). 8 Twiss had been approached in his cell before his conviction by a police officer named Irwin who offered him his life and liberty if he swore that the men responsible for the murder were Messrs Maurice Moynihan, Tralee and Michael Power, Cork who were suspected of being connected with the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IE MOD/77). 9 Parliamentary report in The Daily Express, Friday, 8 February 1895. John Morley spoke in reply to Sir Thomas Esmonde. The following day, Friday 8 February, Dr Joseph Edward Kenny (1845-1900), MP for Dublin College Green, asked the House if a respite could be granted in the case of Twiss pending an inquiry into the truth of the evidence which had emerged since the trial, Morley declined because he said there had been a considerable interval since Twiss’s arrest and trial and could not suppose any further evidence would be forthcoming. Dr Kenny asked if he was aware of the considerable feeling which existed in Ireland about the affair and Morley replied that he saw no reason why the government should interfere with the sentence imposed (Dublin Daily Express, 9 February 1895). 10 Evening Herald, 9 February 1895. 11 Evening Herald, 8 February 1895. Further reference, The Irish Times, 29 March & 4 April 2018, ‘Maamtrasna murders: relatives welcome pardon recommended for Myles Joyce’ and ‘President signs pardon for man hanged for Maamtrasna murders’. 12 The writer added, ‘Is Mr John Morley quite satisfied that he is not going to set up another ghost to haunt his administration?’ Irish Daily Independent, 8 February 1895. 13 The writer added, ‘Mr Morley it seems does not like being taunted by the lords for saving the life of a fellow creature … He and some of his party never tire of expressing their detestations of the Lords, and their desire to end their privileges. But the very suspicion of lordly criticism drives him to refuse the benefit of the doubt to Twiss rather than face it’ (Irish Daily Independent, 8 February 1895). ‘The Chief Secretary, who had refused to reprieve the doomed man, declined to risk prosecuting newspapers which had described the execution as a cold-blooded murder’ (IE MOD/77). 14 Kerry Sentinel, 9 February 1895.