With tract oblique, as one who seeks Access, but fears, side-long he Works his way – As when a ship, by skilful steersman wrought, Nigh river’s mouth or foreland, where the wind Veers oft, as oft so steers, and shifts her sail: So varies he. – Compitum, book 4, p161

During the memorable and unhappy years from 1579, when Earl Gerald was declared an outlaw, to the year 1583, of his murder by Owen Moriarty and Kelly, the wretched inhabitants of the palatinate in Kerry, Waterford, Cork and Limerick were subjected to all the miseries from the ravages of war and reprisal.

The earl became a homeless wanderer, flitting from one fastness to another, ‘sometimes escaping in his shirt,’ and hiding in December weather, ‘up to his chin in a river under the bank.’

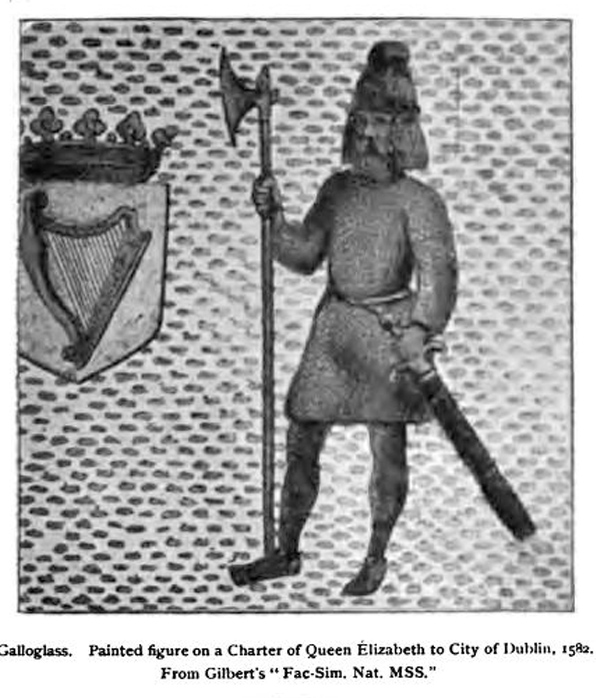

He was reduced from the ownership of the whole County Palatine of Kerry, containing 574, 625 acres of the best land in Ireland, and the leadership of five hundred gentlemen of his own name and race, to a miserable following, narrowed down to some kernes and, for his own immediate attendants, to ‘a priest, two horsemen and a boy, with whom he wandered from one place to another.’

‘I do not know,’ says O’Daly, author of The Geraldines, ‘how to account for the overthrow and extermination of the Earls of Desmond when I reflect on all that they did and endured for religion save by attributing both to the inscrutable ways of God.’1

Like the last of the Tudors or Capets, the last earls bore the unmistakeable marks of the divine vengeance on their lives and works. The father of Gerald was a worthy disciple of his royal master Henry VIII. He divorced his wife, Joan Roche, and during her lifetime married Maud O’Carroll, mother of Gerald and his brother John. He then, like Henry VIII, disinherited his legitimate son Thomas, by Joan Roche, and made Gerald heir of the Palatinate.2

Thomas Rua was declared illegitimate and many calamities followed the brothers in their contentions, for this was a subject of never-ending dispute among them.3

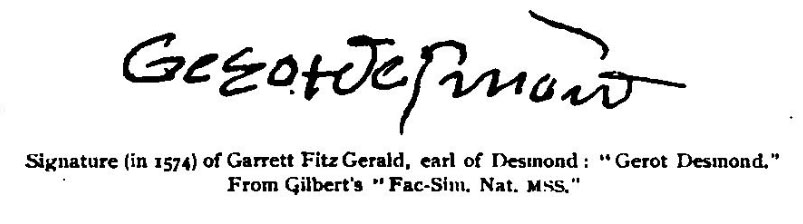

But Gerald himself committed crimes and was guilty of double-dealing, as we see in public records signed and sealed by his own hand.

He glories in having taken up the Bishop of Mayo (Patrick O’Healy) and Father Cornelius O’Rourke, both Franciscans, and of having handed them over to the tender mercies of Drury, ‘who first placed them on the rack at Limerick, beat their arms and feet with hammers, so that their thigh bones were broken, and had sharp iron points and needles thrust under their nails, which caused an extreme agony of suffering … they were then hanged from the branches of a neighbouring tree.’4

The State Papers show that Gerald was playing a double game of ostensibly fighting for the Irish against the queen and of privately ‘settling downe a plotte whereby the traitours might be the sooner overthrown.’5

Nevertheless, Gerald, last Earl of Desmond, had many noble traits of character, otherwise Father O’Daly, in his history, would not have written of him: ‘Much might I write of this noble lord, how steadfast and true he was to his country and religion, how many actions worthy of immortal fame he performed, but as this is not my scope, I leave it to other hands.’

Earl Gerald deserves the great honour of sacrificing everything to save the life of Dr Saunders (Nicolas Sander), a man particularly obnoxious to Elizabeth as he had published a work wherein he proved not only her illegitimacy but that she was the fruit of a most unnatural crime.6

The queen offered Gerald peace and promises to restore him all his possessions and honours ‘provided he delivered into her hands Saunders, the Nuncio from Pope Gregory XIII.’

To those who brought that message the pious earl replied, ‘Tell the queen that though my friends should desert my standard and a price be set on my head for refusing to do her bidding in this instance, I will never give her possession of this man’s person’.

This was a heroic act that ought to obliterate many of his faults and even crimes and to make his name venerated in his home of Tralee.7

It is certain that this unfortunate earl was driven into rebellion in order to crush the power of his family and for the nefarious purpose of sequestrating his vast estates. His fear of his brother John and his jealousy of his cousin, James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, both of whom were his superiors, mentally and physically, were weak points in his character and one of the causes of his ruin.

On the landing of his cousin James Fitzmaurice at Fort-del-Ore (or Fort del Oro) in 1579, Gerald addressed the following letter to Sir Nicholas Malby, the president of Munster. In this letter we see the tortuous policy of the Earl of Desmond.

My very good Lord. Since the writing of my last I received news that Sir James Fitzgerald (Morrish) landed upon Saturday last at the Dingell and burned the town and spoiled all my tenants there and doth spare none of her majesties subjects. I, taking the advice of my Lord Archbishop Cashel and Mr Apsley, they advised me to ride forward with all my forces and with God’s help to expel the traytor and his adherents and now being bent thither, having in my companie, the said Archbishop and Mr Apsley, I hope with the mightier hand of God to make an end of this service on hand. Wishing your lordship to hasten hither with your forces lest that more ayde should come to the rebel. I have written to all the gentlemen and lords within the province to meet with their forces at Kerry to further the service of her Majestie to the furtherance whereof, as I have often told your lordship, I will not spare to venture myself and myn and thus humbly taking leave at Whytestowne the XX July 1579. Your honour’s lordship to command Gerrot Desmond.8

The following letter of Desmond’s to the authorities also throws a clear light on the irresolute and shifting course which he for a while pursued, and also summarises events from July to October 1579.

Erle Desmond’s Defence of Himself After my hartie commendations, and although through envious people there hath been heretofore a little gelose (jealousy) between us, without annie cause offered, I doubt not on either side, whereby our acquaintance hath been the lesse, notwithstanding, I have that good opinion of your good nature, that I hope to find your friendship in alle my good causes, and therefore, thought it gode to certifie unto you what service I have done since the arrival of James Fitz-Morrice, and how little it hath beene regarded. First, before the Traitour arrived, there landed at Smerwicke haven, three Irish scholars in mariners attire, which upon suspicion I caused to be examined, and sent to the Gaol of Limerick; who, in lyne, were known to be gentlemen, and one of them a bishop, who were sente by the Traitours, to practice with the North, to join with him, for which they were by my Lord Justice executed. Upon intelligence had of the Traitors arrival at the Dangyn, I being then in the countie of Tipperarie, have not only by poste testified thereof to my Lord Justice, but also sent warnynge to the citizens of Corke and Limerick, and to all the LL (lords) and gentlemen of the province to have their forces in readiness to expel the Traitour; and with alle speede I marched with such force, as in short time I was able to make over the mountayns to Kerry and so to Smerwicke Haven, where the Traitour, with his companie, fortified a rock compassed round about with the sea saving a narrow passage wherebye menne might passé to the lande; and the 23 Julie, I encamped about him, so as he could neither have victuals from the countrie nor able to send his messengers abroad to his friends, where he was kept so straighte, that his victuals were almost spente. Upon the 26 of Julie, as the Traitor, having the aide of 200 of Flaherties that came to his aide by water, were skirmishing with some of my menne, suddenlie came into the Haven, Captain Courtenay, with a little ship and pynnance, and without any resistance, tooke the Traitour’s shippes, saving one barke that he brought under the forte, where she was broken; so as then the gallies of the Flaherties being ronne away, the Traitour was like in a short time to starve within the forte, or else to yield himself to her Majestie’s mercie. But my unhappie brother John, envying the goode successe of my service that then was likely to ensue, most cruelly murdered Mr Davells, with the Provost Marshall, with their companie, and most unnaturallie enticed my brother James to accompanie him to that detestable acte. Whereof having advertisement, doubting that the executions of so edible (detestable) an acte would practise to destroie me, as often heretofore the said John hath done, and being by the Justice Meaughe (Meade) earnestlie desired (as the rest were) I woulde (rode) to Traly; and from thens, the Justice and I would, over the mountayns, lest that my wicked brethren wold under pretence of friendship enter to Asketyn, and there imbrue their crewel hands with the bloode of my wife and sonne, whom Sir John mortalie hated; and from thence, the 4th of August, to Limerick, to have conference with my Lord Justice about the service; and so returning to Conneloghe, being in camp at Gorestonne, I intelligence that the traitours were upon the fastness of the Grete Wood. I suddenlie went thither, and chased them over the mountains to Kogyrrick-Kearig and from thence to the Grete Wood wither also I pursued them and so still pursued them to Ballincashlaim-Corkemohir, where they were out of all hope to escape; so as eche of them was forced, the 17th of August, at night for their safeguard to scatter, and runne to such places as eche of them toughte beste – so as James Fitz-Morris ran to Owny Mulryan, where he was slaine the xvii of August by my nephews Theobald and Ulick Burke. Sir John also forced to runne to the fastness of Lynamore and Sir James to Glanfleskye, and the Warde of the Forte. Inderstanding that their master was slaine, ranne awaie, and some of my menne entered therein, whereof I having newes hasted me thither, and broke down the fortifications which the Traitour made; whereof I certified the Lord Justice, who sent me word by letters that he would make his repaire into Kerry, wherein he willed me to meete him in the borders thereof, with provisions of beeves for his campe, which I had in readiness, and accordinglie expected his Lordship’s cominge. In which journey certayn of my poor tenants were altogether spoyled of their kyne and cattel, whereof, I having advertisement, made my repaire to the Lord Deputy, about the second of September, to Kylmallock, to understand what suddennesse had altered his intended course; and at my being there, he willed me to gather my intended companye and bring them for his better assistance in the service, the VI of September, nere his campe by the grete wood, which I have done accordingly, and came myself with a fewe companye to understand his lordships pleasure, leaving my menne in campe within two miles of his. After which tyme his lordshippe willed me and the Lord Kerye (Kerry) to declare our opinions, and to settle downe a plotte whereby the traitours might be the sooner overthrown, which plotte we delivered the Lord Justice in writing, the copie whereof I do send you here inclosed, nothing doubting, if the same were followed, her Majesties ministers need not to put her Highness to the charge she is now att, neither the subject so much over-pressed, nor yet the traitours to pass anie waie without their losse. But my reward for the same, and for other services done to my great risk and charges; to my no lesse travel and payne, hath been to restrayne me from libertie, the VII of September, and kept me until the IX of same, at which tyme I was enlarged on condition that I would send my sonne to Limerick. Now in the mene time of my restraint, my menne hearing thereof skattered, and for the most part fledde to the traytours, whereby they being before daunted, were the cccc persons increased and my force by so much weakened. I will not, by particulars, certifie unto you what hindrance I and my tenants did sustaine by my Lord Justice’s being in campe in the small countie of Limerick, neither will I declare the charge I have been at in following the service, which would not grieve me, if the Governor had due consideration to the sonne. The 26th of last month I happened to kill five of the traitour’s menne, whereof were principally Rory-ni-Dillon and Kragory O’Kyne, who were of James Fitz-Morrices council, as such practisers between Sir John and Magberone Mac Enasperk, the other three were Kerrymen. And since my Lord Justice departed the province Sir Nicholas Maltbie (Malby), the forth of this present month, being in campe at the Abbeye of Nenaghe, sent certyn of his menne to enter into Rathmore, a manor of myne, and there murdered the keepers, spoileth the towne and castel, and tooke away from thence certayne of my evidences and other writings. On the VI of the same he not only spoyled Rath-Keally (Rathkeale) a town of myne, but also tyranouslie burned both houses and corne. Upon the VII of same month the said Sir Nicholas encamped within the Abbey of Asketyn and there most maliciously defaced the ould monuments of my ancestors, fired both the abbie, the whole town, and the corne thereabouts, and ceased not to shoote at my menne within Asketyn Castel. These dealings I thought goode to signifye unto you, desiring you, as you are a gentleman, to certifie thereof unto her Majestie and the Lords of the Council, nothing doubting but you will procure speedie revenge for redresse hereof, as also frende me in my good cause, and so I commit you to God, from Asketyn, the X of October 1579. Your assured loving frende.

The slaughter of Elizabeth’s commissioners, referred to in paragraph five of this letter, had occurred when Mr Henry Danvers (or Davells), a gentleman and a soldier, as one qualified by his knowledge of the province and of the individuals, was appointed by Sir William Drury to excite Desmond to meet and repel the Italo-Spanish foes who had landed at Fort-del-Ore.

Danvers, alias Daville, proceeded to the south, reviewed the earl’s military preparations, then advanced to ‘the Dingel’ and having inspected the Fort-del-Ore with a soldier’s eye, returned to the earl’s camp to assure him that it could, with difficulty, be invested and taken.

Danvers, dispirited and disappointed, returned to Tralee, having with him Justice Meade and Arthur Carter, Provost Marshall of Munster.9 They remained at the great castle in Tralee for the night, intending to resume their journey to the Lord Deputy next morning.10

But morning never dawned on them.

About midnight Sir John Desmond arrived and demanded admittance. He ascended rapidly the winding stairs and in a few moments, the three commissioners of Elizabeth were slain. Tradition holds that they were cast down the murdering hole.

Thus Sir John and Sir James became the open enemies of Elizabeth. For this, the Lord Justice ‘showed mercy neither to the strong nor the weak … The blind, the feeble, men, women, boys and girls, sick persons, idiots, and old people, were alike put to the sword.’11

But however guilty Gerald, in not protecting Elizabeth’s commissioners while his guests in Tralee, it is certain the Catholics of the time did not condemn Sir John and Sir James Desmond of the murders.

On the 14th September 1579, Sir William Drury, then encamped against the insurgents, writes to Secretary Walsingham:

September 17. The Earl of Desmond and his brothers campe within a mile of each other; meet together and secrete resorte as some thinke of the principals. And no inmite between their people. Some of the castels whereof the earle offered soldiers to reside for this service are since raised. There is general determination to rase the town of Dingell, lest Ormond should possess it and make their staple there, I do all I can to prevent and surprise the towne by the sea.

In the following letter of Sir Henry Sydney to Walsingham, we see what was the first cause of Sir John and Sir James Desmond’s rebellion and the reason why they killed those emissaries of Elizabeth:

Sir John being come to Dublin for conference with the Lords Justices, was, together with his brother the earl, sent prisoners and committed to the Tower of London where they remained, I think, seven years after; and truly, Mr Secretarie, this kind of dealing with Sir John of Desmond was the origin of James Fitzmaurice’s rebellion, and, consequently, of all the royle and mischief in Munster, which I can prove hath cost the Crown of England and that countrie one hundred thousand pounds.

There were other causes for John and James Desmond’s revolt and a principal one was they were denied the free exercise of their religion, for both Sir John and Sir James were sterling Catholics and hence sacrificed everything on earth for their holy faith.

Sir James Desmond had a powerful enemy in the wife of the earl, his half-brother, as we see in the work of Russell, a contemporary author, who is especially indignant against this lady and indeed, in his longer letter, vented his rage on the entire gender:

See what spring from ye malice of woman. For Dame Elleynor Butler, Countesse of Desmond, and the mother of one only sonne, opposed herself against this James Fitzmaurice, and with reasons, persuasions, tearses, and imploreings, persuaded the earle, her husband, not to dismember his patrimony, but rather for to leave it whole and entire to his only son, James Fitzgarrett, who was then a young child.12

Sir James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald

Sir James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald was the son of Maurice Dhuv or Maurice a Tothane, the Fire-brand, who, with his own dagger, carved out his fortune and his name by the foul murder of his cousin James, 13th Earl of Desmond.

This deed of blood seems to have been the commencement of the final ruin of the House of Desmond for it was the original cause of the disputed succession in the case of Gerald, the last earl, who disinherited Thomas, the oldest son and only legitimate heir of James, 13th Earl of Desmond.

Maurice Dhuv received, as the ‘wages of his iniquity,’ the Barony of Kerricurrihy in the County of Cork from his brother James, the 15th earl. This was, however, granted by James to save himself from the near neighbourhood of Maurice, whose violence he dreaded.

Gerald, the next earl, ignored this grant of Kerrycurrihy and leased the barony to Sir Warham St Ledger for £100 a year. He thus most unjustly deprived his cousin, Sir James, of his inalienable right to these lands.

Notwithstanding this injustice, Sir James imperilled life and limb for Gerald’s liberty when he and his brother were immured in the Tower of London for six years.

The Annals of the Four Masters speak of this as a superhuman act of heroism on the part of Sir James Fitzmaurice. Here are their words in their roundabout Irish style:

It happened through the miracles of God and the exertions of James that the Earl of Desmond and his brother John, who had been in captivity in London for six years, were set at liberty by consent of the English Council, and they arrived in the harbour of Dublin. The earl was taken and put under arrest in the town and John was permitted to visit the wilds of fair Munster and to visit his patrimony and the surviving remnant of his followers.

This unjust imprisonment of Sir John and the earl is reaffirmed as the original cause of the rebellion of Sir James Fitzmaurice, as Sir Sydney Smyth admits in his letter to Secretary Walsingham:

And truly, Mr Secretary, this harde dealing wyth Sir John of Desmond was the origin of Sir James Fitzmaurice’s rebellion and consequently of all the evils in Munster.

He then shows the progress of events at that time:

With easie journeys I came (from the North) to Dublin where I had not been but a whyle but that James Fitzmaurice, sonne of Maurice of Desmond (nicknamed Maurice Attotane), brother to James, Earl of Desmond, father to the now earl, traitor and rebel, understanding that I was arrived, and had not brought with me neither the earl nor Sir John, his brother, which he thought I might and would have done, assembling as many of the Earl of Desmond’s people as he could, declared to them that I could not obtayne the enlargement of either the earl or his brother John and that there was no hope for either of them but to be put to death or condemned to a perpetual prison; and therefore (seeing that the country could not be without an earl or a captain) willed them to make choice of one to be their earl or captain, as their ancestors had done after the murther (as he termed it) of the good earl, Thomas Fitzjames, his ancestor, put to dethe by the tyrant, the Earl of Worcester (as he called him), then Deputy of Ireland, and according to this (his speech) he wrote unto me. They forthwith, and as it had been with one voyce, cried him to be their captain, and him they vowed to follow and obey his commandment … and he assembled forces, not much extraordinarie, but full as much as it had been accustomed by any earl or captain, which it was by me forbidden and accordingly forborne by Sir John of Desmond. Upon consideration of his letter and other advertisement of his doings I writt unto him and used, all other, the best mediation I could, that he should desist from that unlawful usurpacion. He answered me frivolously, then used threats, but all I could do would not serve, but the more I writt the worse he did; and persisted still in assembling of men of warre to the great annoyance and burthen of the people of his own country and neighbours, whereof they greavously complained, but I by no means could redress it. Here may you, sir, as I writt before, see the origyne of the rebellion in Munster.

O’Sullivan gives a more graphic account of the rebellion of Sir James Fitzmaurice in the following words:

James Geraldyn, son of Maurice, Earl Gerald’s uncle, being inconsed at these things, refused to own the queen’s authority until his relatives were set free; hence grew civil war. Other relatives, nearly all the earl’s dependants, and almost all the Munster Geraldines sided with James, as did others of Munster; particularly the chiefs of the MacSweenys, my uncles, named Edmond, Eugene, Murtagh, some of the men of Beare, under my father, Dermot O’Sullivan, and other spirited young men (alis juventus animosa). The queen ordered her Irish viceroy to make preparations against the rebels – she easily revived the old jealousy of Ormond against the Geraldyn – she excited Thomas Ruagh, the earl’s eldest brother, a man of weak mind, with the hope of obtaining the earldom and make him governor of Desmond, which he probably thought the next step to the title. She relaxed persecutions, appealed to the Irish chiefs, telling them that she was contending not for religion but for her right to reign; but war having begun, James carried it on in his own person and by his lieutenants, the MacSweeny chiefs, with wonderful success, nor did he desist from his undertaking until his cousin the earl, and Sir John, were released from prison and restored to their rights and he himself had obtained a full pardon.

Two years after this ‘full pardon’ of Sir James Fitzmaurice, Earl Gerald, and Sir John, his brother, made their escape from Dublin after which they were declared traitors and a reward was offered for the earl’s apprehension.

At about this time Sir James wrote (very probably to Walsingham) for protection for twenty years but receiving a vague answer from London and fearing that he would not be safe from the English in Ireland, he fled into Spain with his wife and children.

For three years this indomitable hero wandered about the continent striving to persuade the kings of France and Spain to take up the case of the down-trodden Irish nation.

In France his request was politely refused, as Henry III wished to remain on good terms with Elizabeth. Philip the II, however, sent him to the pope. In Rome, Sir James met Captain Thomas Stukely, a soldier of fortune, said to be an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, and induced him to join his expedition to Ireland as admiral of the fleet.

The Right Rev Cornelius O’Mulrian, Bishop of Killaloe, and a Franciscan, caused Dr Allen and the celebrated Dr Saunders to accompany Sir James. This truly patriotic Irish bishop got a Bull from the pope encouraging Irish Catholics to fight under the standard of Sir James Fitzmaurice for their faith and country.

An expedition was immediately equipped at the expense of the pope. Sir James sailed from Ferol, a port in the Kingdom of Galicia, on the 17th June 1579. He had only three shallops besides his own vessel as Stukely had deserted him and followed the fortunes of Sebastian, King of Portugal, in his expedition against Morocco.

One month later, on the 16th July 1579, Sir James arrived at Dingle and on the 25th he was joined by two galleys which carried a hundred fighting men.13 The little squadron left Dingle on the 17th or 18th July and arrived at Fort-Del-Ore, which they fortified as well as they were able.

After having landed, Sir James sent the following letters to Austin Kittagh MacDonnell and to Randal McDonnell which were intercepted by the English. These letters were evidently written in the vernacular Irish.

He also wrote to his cousin, Earl Gerald, and we see that Gerald wrote to him through his servant, Danubi, whilst, at the same time, the earl sent a most loyal letter to the government against Sir James.

James Fitzmaurice to Austin Kittogh MacDonnell, July 18 1579. Life and health with thee, O writing, to Austin Kittagh MacDonnell, from his own friend and companion, James, son of Maurice, son of the earl. And be it known to him that I have come safe to Erin with power, after all I have travelled and traversed of foreign countries; and for this reason I implore of him to come to me with as many bonaghtmen as he can bring with him; and, moreover, be it certain unto him, that he never came to any war coming into which he should have greater courage, than this war, for many reasons: first inasmuch as we are fighting for our faith, and for the church of God; and next, that we are defending our country and extirpating heretics and barbarians, and unjust and lawless men; and besides let him understand that he was never employed by any lord who will pay himself and his people their wages and their bounty better than I shall, inasmuch as I never was at any time more competent to pay it than now, thanks be to the great God of mercy for it, and to the people who have given me that power, under God, and who will not suffer me to want from henceforth. And this is enough; but let him not neglect coming, that he may get some compensation for all the toil and labour that he suffered in my cause before now; let him request his brethren, and the gentry of his territory, to respond to the time, and to rise with one accord for the sake of the faith of Christ, and to defend their country; and moreover, that all their bonaghtmen will get their pay readily; and that we shall all get a place in the kingdom of heaven, if we fight for his sake.

These words sound differently in the vernacular for in Irish, they went straight to the heart and sentiments of our faithful forefathers of that time. To receive a regular daily pay in war and to be assured of the kingdom of heaven if they die fighting for faith and fatherland, were strong incitements to our people to rush to the standard of the good Sir James.

James Fitzmaurice to Randal McDonnell, July 31, 1579. The custom of the letter (ie) salutation, O billet, from James, son of Maurice, son of the earl, to his friend and companion Randal, son of Colla Maeldubh, and tell him that I told him to collect as many bonaghtmen as he can, and to come to me, and that he will get his pay according to his own will, for I was never more thankful to God for having great power and influence than now. Advise every one of your friends (who likes fighting for his religion and his country better than for gold and silver or who wishes to obtain them all, ie, to fight for his religion and country and also for gold and silver as his wages) to come to me, and that he will find each of these things.

Here again he promises the rewards of the present as well as the eternal riches of the future to those who fight for their religion and country.

The following letter, written at the same time, clearly shows the unhappy, temporising policy of Earl Gerald:

William of Danubi, Servant of the Earl of Desmond, to James Fitzmaurice, July 18 1579. Life and health from William of Danubi to James, son of Maurice; and be it known to James that my master sent him his blessing, and that unless James relieves us soon we are undone; for John is in prison awaiting my master, and so watched and warded that he may never go away again. And therefore, I beseech you, in the name of God, and in the name of my master, to bring relief soon or you will not be able to overtake the relief of him and to cooperate with the good helps (which now offer) such as the sons of the Earl of Connaught, and many others of the men of Erin. And moreover, be it known to you, that whatever Edmond Brown has said, nothing shall be wanting of it, whatever may be added to it; and be assured of it, that we cannot tell how much we are in want of you; and though we would like that a host of men should come along with you, that we would be exceedingly glad that yourself alone should come to our aid; and be not dismayed by what hardship you have seen, for we think that the greater part of the men of Erin are ready to rise with ourselves and we would be much the better of you. And do not wait for the harvest, for there is danger that the whole affair may be set aside by that time. And we would incite you more than this, if we thought you would respond to us sooner. And be assured that I do not write this of my own accord, but at the request of my master, and that it is dangerous to write from Erin to you; for the letter which the Seneschal wrote at Ballynaskellig, to be sent to you by the merchant of San Malves, (miscarried), that merchant, and MacCarthy, who was that merchant’s gossip, betrayed the Seneschal, and MacCarthy brought the letter to Portlairge, where the justice and the president were. And the form that was, it was: ‘Life and health from John, son of William, to James; and be it known to James, that the wheat of the friars has grown well and that the wheat of the country has failed. And God saved the Seneschal on that occasion.’ I have news, except concerning the death of MacCarthy Reagh; and that Rory Oge O’More has not left a stake or a scallop in Naas-of-Leinster or in twenty miles of every side of it; and not only this, but that the flame of war has grown up in many of the men of Erin against the Saxons, if they could but get help. That is enough, but give a blessing in the name of my master, the King of France.

Sir James, in the meantime, departed from Fort-Del-Ore in the month of August 1579 and rode inland to the County of Limerick and arrived at the territory of his relatives the Burghos, or Burkes, of Castleconnell. Here he seized on some horses belonging to Theobald Burke and his brothers.

On hearing of the raid they called out their men and followers and took possession of the ford beal-an-atha-an-borrin supposed to be Barrington’s bridge, about six or seven miles from Limerick. When Burke came up, Sir James said, ‘Cousin Burke, the taking of garrens between you and me should not be a breach.’

Burke, however, attacked him and a fatal engagement followed which ended in the death of both Sir James and his opponents, the Burkes, as we see in this contemporaneous account of O’Sullivan:

James, with eight horsemen, and eighteen foot soldiers, under the command of Thadeus McCarthy, set out on foot to excite to war those of the Irish to whom before his departure from Ireland he had communicated his plans. On the road there met him Theobald Burke, Lord of Castleconnell, with his brothers, Richard and Ulick, and a superior force of horse and foot. These, though Irishmen, Catholics and relatives, yet urged by insane folly to prove their loyalty to the queen, attacked him with missiles from a distance. James had already passed the ford of Beal-an-atha-an-Borrin and the Burkes were in it, when being hit by a leaden ball (plumbeaglande), in anger he faced his men about; they fought for some time with more heat than hurt at either side. At length James, giving spur to his horse, and followed bravely by his men, attacked the enemy still struggling in the ford, drove at Theobald Burke with his sword drawn and struck him such a blow beneath his helmet that he clove his head in sunder, and scattered his blood and brains on his breast and shoulders. On the death of Theobald, the Burkes retreated from the ford pursued by James. Of the Burkes perished with Theobald, the leader, his brother Richard, and William Burke, a knight; his third brother, Ulick, was also mortally wounded, Sir Edward O’Mulrian lost his eye, and many more were wounded and missing. Of the other party James alone died within six hours of the wounds he had received, having first had absolution from a priest he had with him; eighteen soldiers were wounded, among whom a Geraldyn called Black Gibbon, having received eighteen wounds, was left hidden in the copsewood and secretly cured by a friendly surgeon … The rest of James’s band, having lost their leader in this unnatural (cadmeo) conflict, returned to Sir John of Desmond.14

The letters of Sir James Fitzmaurice show him in the brightest light of a chivalrous, brave and religious leader, and the only one who could fight, with any hope of success, Ireland’s battles at the time. His greatest enemies were obliged to acknowledge that he was an extraordinary bold politic and learned Irish leader.

He died for his faith and his country with the blessing and special protection of the vicar of Jesus Christ on his work. What greater honour can be granted to a Catholic and a Christian soldier of the cross than to die thus, for God and fatherland.

Yes, greatest son of the Desmonds:

We need not mourn for thee, here laid to rest, Earth is thy bed, and not thy grave; the skies Are for thy soul, the cradle and the nest; There live for ever, thy glory never dies; For like a Christian Knight, and champion blest, Thou didst both live and die. – Yassa

It is a melancholy duty to be obliged to chronicle the terrible afflictions that befell him and all his family on account of the crimes of his father. His two sons, Maurice and Gerald, were left with Cardinal Granville to be educated at Madrid. Daly says they were youths of singular promise and were well received at the Court of Philip of Spain.

A nephew of Cardinal Granville took such an interest in both that when the elder Maurice died at Madrid he accompanied the younger, Gerald, to Ireland in 1588 and they both perished by shipwreck. Thus ended the race of Maurice Dhuv and of Sir James Fitzmaurice, the bravest of the brave, of whom it can be in all truth preconized:

A braver soldier never crouched lance, A gentler heart did never sway in court: But kings, and mightiest potentates, must die; For that’s the end of human misery. – Shakespeare

Closing in: The Final Days of Gerald, Earl of Desmond

Notwithstanding the sufferings of Sir James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, it is the long and unceasing sufferings for the Catholic cause of his cousin, Earl Gerald, whose heroic endurance of poverty and the dereliction of all his followers – as well as his own tragic death a few years later – that have caused his memory to remain enshrined in the hearts of the Irish people.

Gerald’s head, cut off by Kelly on instruction from O’Moriarty, was carried to the Earl of Ormond, the Earl of Desmond’s stepson, who had it pickled and placed in a pipkin and forwarded as a present to Elizabeth.

It was accompanied by the following letter:

Ormond to Walsingham I do send her Highness (for proof of the good success of the service, and the happy end thereof) by this bearer, the principal traitor, Desmond’s head, as the best token of the same, and proof of my faithful service and travail, whereby her charges may be diminished, and as to her princely pleasure shall be thought meet. Thos, Ormond Et OSS Nov 29th 1583.

The head was impaled on London Bridge, according to the barbarous custom of the times. His body lay for some time at Glanageenty and was then removed to the little chapel of Kilnanamanagh near Castleisland, the family cemetery of the great Geraldines.

Owen Moriarty was guilty of the murder of the last Earl of Desmond. This we see clearly proved in the following letter of Owen to Ormond in which he gives us the names of those who perished in their great leader’s overthrow and the circumstances to which Gerald had been reduced:

Ye shalle reade as follows the names of some fewe of the chiefest that were slayne, being leaders of companies, and menne of account among the traitours: Henry Fitz-Gerald (base brother of Syr James Fitz-Gerald of the Decies); Kennedy MacBrien (MacBrien O’Goonagh’s sonne); Gibson Roe, Lord of the Great Wood; the Deane of Broghill’s sonnes; the Earl of Desmond’s receiver, Connagher O’Mulrian; Daniel Mortagh, foster-brother to Sir John O’Desmond; Rorie Moel MacConaghane, MacThomas, chief of his name; Maurice Vale, James Vale-Brownes, of the Earl of Desmond’s foster-brother;15 William Grange, son of MacBrien O’Goonagh – besides two hundred and forty-six menne and confederates that were putte to the sword and executed. Thus was the Erle of Desmond and alle his force consumed and left accompanied only with seven menne and his prieste, who, from the tenth of last March 1583, hidde them in a glinne within Sleave-Luachra, having no other foode for the space of seven weeks than but six plowe garrans whereon they fedde without bredde, drinke, or any other sustenance. About the 20th September last, Desmond being hardlie followed by certaine Kearnes, appointed by the Lord General to serve against this traytour, his priest was taken from him with anothere of his menne and brought to the Castle of Ormond. Since which time, the erle being relieved by a Captain of Gallowglass called Gohorra MacDunaha MacSwynie, the Earl of Ormond having advertisement, pursued him into O’Leary’s countrie, where he tooke most of his goodes – insomuch that last November the said Gohorra was enforced to repayre to Inniskive (MacCarthy Reagh’s country in the County Cork) and there took 15 cowes and 8 garranes from one O’Donoghue MacTeige of Inniskive aforesaid – which Donoghue, with ten more of his companie, made pursuit – rescued his cows and garrans – slew said rebel Gohorra, and sent his head to the Earl of Ormond. The 11th of said November the Earl of Desmond, for want of said Gohorra, was urged by meyr famine, to send to one Daniel MacDaniel O’Moribertagh, to seeke some relief, which Daniel made answer to him, that he was sworn to the Lord General, and had delivered his pledge for doinge good service against Desmond and his adherents wherefore he would give him no relief at alie.

The following is Ormond’s letter about Owen Moriarty:

Ormond to the Privy Council I received certain word that Donal Moriarty (of whom at my last being in Kerry I took assurance to serve against Desmond) being accompanied with 25 kern of his own sept, and six of the ward of Castlemaine, the 11th of this month (Nov 1583), at night, assaulted the Earl in his cabin, in a place called Glanageenty, near the river of the Mang, and slew him, whose head I have sent for, and appointed his body to be hung up in chains in Cork.16

Owen Moriarty, however, committed an act of vengeance on this occasion as we see in the following statement about the final pursuit and murder of Earl Gerald, sworn by Moriarty on 26 November 1583, about two weeks after the killing.

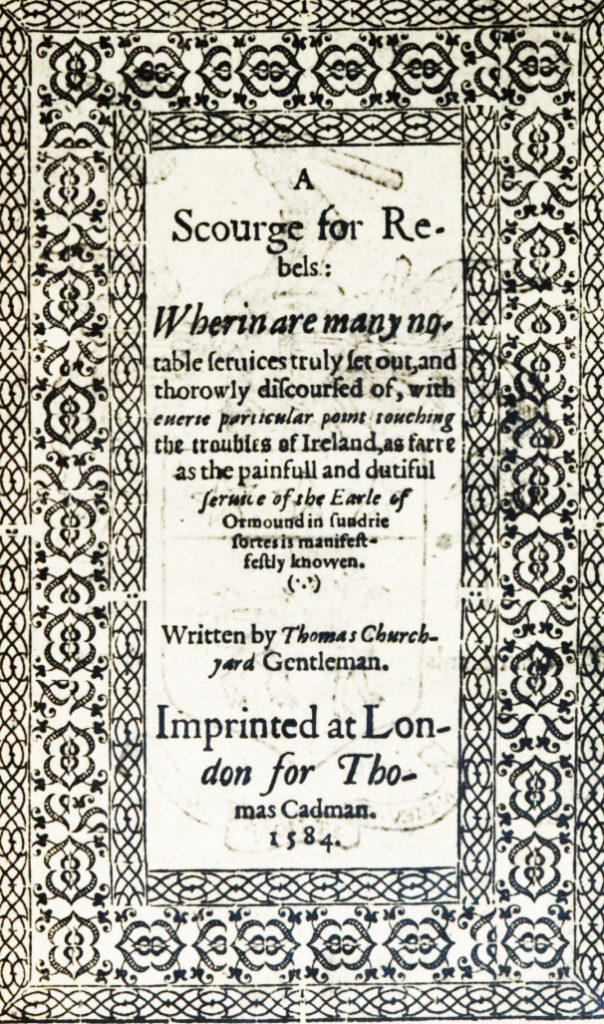

According to this statement, published in 1584, the earl, after being wounded in a cabin at Glanageenty, was carried for some distance by O’Moriarty’s men who, being tracked by the earl’s followers, decided it was too dangerous to continue with him alive and so beheaded him.17

It is to be lamented that history cannot provide a like statement by Gerald.

The Examination of Owen mac Donill, Omorihertegh, taken the xxvi of November 1583 before those whose names are hereunto subscribed, of the manner and discourse how the Earle of Desmound was pursued and slayne. The said Owen being duely sworne and examined uppon the holie evangelist, by vertue of his othe, deposeth, that on Saterday (beeing the ix. of this present November) the Earle of Desmound departed, the woods lying neere the Iland of Kierye, and went Westward beyond Tramore to the wood called Doiremore neere Bongoinder, from whence he sent ii. of his Horsmen (called Conoghore Nescolly & Shane Deleo) with xviii. kearns to bring him a pray (having himself and Iohn mac Ullug, and two or three footmen stayed there at Doiremore for them) which company (by the said Earles direction) went to Cahir nefahye (lying by west Gregories Castle by the Sea side) and there tooke the pray of Maurice mac Owen brother in law to this Deponent, and the pray of Robert mac Edmound being Tenauntes to this deponent and to his eldest brother, called Donil mac Donil Omoriherteighe in that town: that is to say, fortie Cowes, niene capples with great store of other goods and houshold stuffe, and stripped naked the said Maurice his wife, and children. At the takinge of whiche praye (to terrefie the people from making pursuit) the said traytors published and saide that the Earle of Desmound lay neere them with the rest of his companie, to ayde them, if pursuite had beene made after them. Whereuppon the saide Maurice sent worde to Liuetenant Stanley (then beeing in the Dingle) and also to this deponent and to his sayd brother Donil mac Donil (being then at Castle dromin neere Castle Maing) of the taking of his pray. Whereuppon this Deponent and his said brother Donill mac Donil (having also word sent them from Lieuetenaunt Stanley, to pursue and tract out that pray, and to call to their ayde, the ward of Castlemaing, and that he and the countrey were making ready to followe them to rescue the same) having respect chiefely to their othes, assuraunce, and promise given and made to the Lorde General, to doe service, set forwarde, being xiiii. proper Kearnes in companie whereof two were shot. And this Examinate went to Castlemaing, and tolde the Cunstable Cheston of the whole matter, and besought him to rise out (according to the Lieuetenaunts direction) to followe the praye in the companie of him and his brother Daniel, to which Cheston aunsweared, that he could not himselfe depart his charge, and saide, he woulde let him have some of his companie, to go with this Examinate, and so sent away five Souldiers with him. This Examinate, and those five Souldiers came together to the Mountayne of Sleavemisse, where his Brother Daniell mac Daniell wayted for them, and from thence they came altogether toward Tralye in the Evening a Sunday (beeing the tenth of November) in hope that they shoulde overtake the praye, before the same, shoulde passe the straight of Tramore, where they were sure (as they thought) to rescue the same praye from the traytours if they had overtaken them there. At their comminge to Traley, they found the tracte of the pray, going Eastwarde to Sleaveloghra. Whereuppon, the Souldiers whiche came from Castlemaing beganne to stay, and sayde they woulde traveyle no farther after the praye, but turne backe to theyr charge, till at length this Deponente perswaded them to staye, and keepe him company to pursue the pray, promising them two biefes of the pray if it had beene theyr lucke to rescue the same from the Traytours, if not, that he woulde give them a Biefe of his owne in respecte of their travayle. Uppon whiche promise, the Souldiers agreed to goe forwarde: the tracte was followed by daye light to Balleore, and by mooneshyne towarde Glamagnitie at Sleaveloghra, where then the Elder Brother Daniell, and this Examinate tooke advice to gette uppe above the Glinne to viewe whether they might see anie fire in the Woode, or heare anye stirre, and having come to the heyghte over the Glinne, they sawe the fire underneath them. Whereuppon Daniell sayde that he woulde goe to spy, whether the Traytours had the praye there with them, whiche hee did, and came backe to the companye, and tolde there were some of the Traytours there, whiche hadde no Cattell with them, and sayde it were beste not to assaulte them beefore the praye and them selves coulde bee founde together. Whereunto this Examinate agreed. In the dawninge of the daye, on mundaye the eleventh of November, they put themselves in order to set uppon the Traytours in their Cabbins. This Examinate and his Brother Donill with theyr Kearne, tooke the forewarde, and appoynted the souldiers to keepe the rewarde (savinge that one Daniell Okelleye a Souldier whiche hadde but his Sworde and Target, stoode in the forewarde with them) they all makinge a greate crye entered the Cabbin where the Earle laye, and this Examinate ranne thorowe the Cabbin after the Earles companye, whiche fledde to the Wood, and at his retourne backe to the Cabbin doore, the Earle beeynge stroken by one of the companye (by whome certayne hee knoweth not, but that all the Footemenne and Souldiours were together within the Cabbin) hee discovered him selfe, sayinge: I am the Earle of Desmounde, save my life. To whome this Examinate annsweared, thou hast killed thy selfe longe agone, and nowe thou shalte bee Prisoner to the Queenes Maiestye, and to the Earle of Ormounde Lorde Generall of Mounster. Wheruppon hee tooke him by his arme (beeing cutte,) and willed the Earle (who was slowe in going) to make speede, else they woulde carrye awaye his Heade, seeynge the Traytours drewe verye neere to have him rescued. Whereunto Daniel mac Daniel sayde, I will carry him on my backe a while, and so shall every one of you. Daniel carried a good while, and being weary he put him off: the Traitours being at hand, al the companie refused to carry him any further, considering the eminent danger they stood in the traitours drawing neere. Whereat this deponent Owen mac Donil willed the souldier Daniel O kelleye, to cut off the Earles head, for that they could not apply to fight and carry him away, to whose direction Kelley obeyed, saying: he would so doe, drawing out his sworde, and striking off the Earles head, whiche they brought to Castle maing, where this Examinate and his brother Daniel mac Daniel delivered the same to be kept (as in her Maiesties Castle) til they had made themselves ready to bring the same to the Lord General, and have sent woorde to Lieuetenaunt Stanley (who followed them in armes with the force of the countrey, having the charge of the service in those parts by the L. Generals appointment) of their happye successe, & willed him to take his waye to Castle maing, to meete them who came thither with his companie. And the forenamed Daniel O Kelley (being likewise examined before these, testified that the Earle of Desmounde was pursued in the order and maner afore written, and that he him selfe wounded the said Desmound within his Cabbin, and after cut off his head (least he should be rescued) and that hee the sayd Daniel mac Daniel layd up the same head to be kepte at Castlemaing, til it had beene brought by them to the Lorde General. These thinges beeyng saide by othe before the right Honorable the Earle of Ormound, the Bishop of Oshry, and the Soveraigne of Kilkenny.18

O’Sullivan, a contemporary, thus relates the end of the murderers of the earl:

Both Moriarty and Kelly died by the gallows … Kelly in England for some crime … Moriarty in Ireland, being executed by the Lord of Lixnaw.

Moriarty and Kelly were guilty of the murder of the earl though he cried out to them in the words of the poet,

Thou shalt do no murder; Wilt thou then Spurn at his edict, and fulfil a man’s? Take heed; for He holds vengeance in His hand, To hurl upon their heads that break his law. And art thou yet to thy own soul so blind, That thou wilt war with God, by murd’ring me.’ – Shakespeare

Tradition holds that Moriarty had ever afterwards that sting of conscience that mutinies in a man’s bosom and that raises a furious tempest in the soul. ‘For fifteen years,’ says O’Daly, ‘remorse tortured Moriarty in soul and body. He was shunned by everyone, and universally execrated.’

Many a time he cried out for mercy, one we are sure he obtained for his family though he himself was gibbeted at his own door by the Lord of Lixnaw on account of this infamous crime in slaying the earl, his suzerain and foster brother.

Kelly, however, whose conscience was in the Earl of Ormond’s purse, deserved no mercy for he gloried in having committed this atrocious crime.

Moriarty and Kelly, before this murder, could hear re-echoing in their ears the words of Shakespeare, which were written about the same time –

Which of you, if you were a prince’s son, If two such murderers as yourselves came to you, Would not entreat for life – (Spare me, I am the Earl of Desmond!) As you would beg, were you in my distress, A begging prince what beggar pities not! – Shakespeare

Thomas Fitzgerald, son of Lord Offaley, having married a daughter of the O’Moriarty, claimed a portion of Iar-mond in right of her; from him grew the Palatinate of Desmond, and the power and glory of the Geraldines.19

Is there not a singular providence in all this, that the very family who introduced the Geraldines into Kerry, and the first Irish blood that mingled with the conquerors, should be the cause of the death and ruin of the last of those great lords of Desmond.20

_____

The above essay was written by Father J Prendergast, a member of the Franciscan Order in Killarney, in the last years of the nineteenth century. A biographical notice of Father Prendergast is found in Muckross Abbey: A History, to be published shortly.

_____

1 ‘If curiosity would induce you to ascertain what dark deeds of theirs may have brought upon them such terrible retribution, ponder well how James FitzThomas, Earl of Desmond, was murdered in his castle at Rathkeale by, as some suspect, his brother John. Again, recall the murder of James FitzMaurice, perpetrated by Maurice of Desmond in the days of Henry VIII. Should not this satisfy you, I would have you to meditate on all the cruel acts of rapacity and blood committed on the MacCarthys’ (The Geraldines, pp134-135). And I would add the abominable cruelty committed against the O’Connors, one of which the most atrocious and most diabolical in the history of any nation. 2 James Fitz-John Fitzgerald left three sons, Thomas Rua – ‘the Red’ – born of Joan, daughter of Viscount Roche. The earl divorced Joan Roche in order to marry Maud O’Carroll, mother of Gerald and John. 3 William Wise, Sheriff of Waterford, in a letter to ‘Crumwell’ writes, ‘James of Desmond has sent over to England his son Thomas, whose mother is the Lord Roche’s doghter, whom he put away and now occupyeth O’Karrol’s doghter, by whom he had issue.’ (Lamb, Lib v602, leaf 105). One year after the above letter to the Sheriff of Waterford, the ‘pretended earl’ seems to have taken a third wife, according to Ormond’s letter to the council: ‘Kildare’s son-in-law have lately married O’Brine’s (O’Brien’s) doghter, and combined with James of Desmond in such wise, that he have married his sister to the said James.’ Whether his first wife, Joan Roche, was alive or he still continued to ‘occupye’ O’Carrol’s daughter is not stated, says Gibson. ‘He was indeed,’ says this veracious author, ‘walking in the footsteps of his royal master.’ We are indebted to Mr D C Coltsmann Esq, Glenflesk Castle, for our copy of Gibson’s Cork and also for his having drawn our attention to this excellent digest of the State Papers of the time. We have in the life of John of Callan a more outrageous example of this crime of adultery according to our great Irish archaeologist O’Donovan: ‘Thomas Fitzgerald, Knight of Glyn, descended from John Morn a Sursainne, son of John of Callan Fitzgerald, who was slain at Callan by Finghin Reanna Roin MacCarthy in 1261. The mother of this John na Sursainne had been the wife of O’Coileain (now Collins) of Claenghlais but John of Callan slew O’Coileain and kept his wife a concubine. The Knight of Kerry descends from Maurice Fitzgerald, who was another bastard son of the same John of Callan by the wife of O’Kennedy. The aboriginal Irish, says the learned O’Donovan, were cruelly treated by those haughty Geraldines of Desmond on whom a curse seems to have fallen for their crimes (Tribes of Ireland, p74). 4 Further reference, Seventeen Martyrs (1990) by Desmond Forristal, Chapter One, ‘The First Martyrs Patrick O’Healy and Conn O’Rourke’, pp9-15. 5 The double dealing of this unhappy earl is inexplicable to us unless we conclude with Archdeacon Rowan that ‘these times of civil war and dissensions breed time-serving, double-dealing and treachery in all quarters, from the highest to the lowest.’ 6 Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism by Nicolas Sander translated by David Lewis (1877). 7 ‘Yet, we are forced to say, we were pained and ashamed at the sight of the spot where he was murdered, that no monument, nor even a wooden cross, has been erected over that historical earth-mound which put an end for ever to the great Geraldine family. Could not some of our many societies of Tralee subscribe a few pence to buy even a poorhouse cross to place over this historical temporary grave of the great Earl of Desmond?’ 8 Archbishop of Cashel was the apostate bishop, Myler MacGrath, who returned to the church before his death. William Apsley was of Hospital, County Limerick, a great man in the south of Ireland in his day; his co-heiress married Sir Thomas Browne, ancestor of the Earl of Kenmare and thus brought the Hospital estates into this Catholic family. 9 Philip O’Sullivan, a contemporary writer, in his Catholic History, stated: ‘John, at Tralee town, making an assault upon Danvers, a magistrate; Arthur Carter, marshall of Munster, both English heretics; also one Meade, one of the judges and Black Raymond put them to death with some others and chased the rest of the English out of the town.’ 10 Father Prendergast, who wondered why Denny Street was not called Geraldine Street, described Tralee Castle as ‘the centre of all the warlike manoeuvres of the great Geraldines for centuries. It was, above all, the home of the founder of the priory of Tralee, which has produced so many learned and holy men for the church in Ireland.’ A description of the appearance of the castle as it was in the first quarter of the nineteenth century was given by Archdeacon Rowan in his antiquarian researches of Kerry and is reproduced in Father Prendergast’s history; it begins: ‘Tralee Castle as it now rises in the mind’s eye of one who looked on it thirty or forty years ago was a building partly ancient and partly modern, standing in what was once a courtyard but become by neglect and disuse a filthy enclosure which we can remember converted by land agents to the vile uses of a common cattle pound. It turned its back on the present Main Street or Mall and extended its front, looking southward, for nearly three hundred feet over what in those days used to be called the bowling-green, round which a promenade of limited extent was thrown open to the inhabitants of Tralee; and many a summer’s evening has the writer seen that circular walk thronged by promenaders as gallant as the exclusives of the Ring in Hyde Park.’ For full account, see Kerry Sentinel, 9 October 1897. 11 Quotation from Four Masters. The Lord Justice was Sir William Pelham (died 1587). See Dictionary of National Biography. 12 Russell continued: ‘If often falls out that women in their requests prevaile with men, and even as the soft wave of the sea cleareth and pierceth the hard rock, not by force, but by continually falling thereon, so the Earle of Desmond being incessantly advised by his wife or lady or rather (as I believe it) not well established in his wits, without any consideration or respect had of his said cousin’s greate merritts, and former services done for him, or the expectation of future services, utterly rejected his suite, gives him nothing, so as it ended in an absolute denyall.’ Further reference, As Wicked a Woman: the biography of Eleanor Countess of Desmond 1545-1638 (1997) by Anne Chambers. 13 They were captured a few days afterwards by the English. 14 Sir Theobald Burke and his brothers who thus fought against their country were near relatives of Sir James Fitzmaurice, as the latter addresses Theobald as ‘his cousin.’ The Burkes, in fact, were cousins from both father and mother, ‘something more than kin though less than kind.’ Theobald’s mother was a Geraldine by father and mother, and was also first cousin of Sir James, being daughter to his aunt, sister of Sir James, 15th Earl of Desmond. Then James’ mother was of the House of Ryan of Awney (O’Mulrian) which, by the masculine and feminine of its children – a trait which they retain to our day, as we have never known a Tipperary or Limerick Ryan without this characteristic – spread itself into a perfect network of relationship among all the great English and Irish families of Munster which, as Archdeacon Rowan remarks, is ‘curious to consider and most difficult to unravel.’ We find here in O’Sullivan’s account of this fatal engagement an O’Mulrian riding with Theobald Burke while Theobald Burke’s son and successor was married to an O’Mulrian of Awney. The father of the Burkes of Castle Connell was rewarded by Elizabeth for Theobald’s treason to his country with a baronetcy and a pension, on the 18th May 1580. The loss of his children, however, outweighed all these honours and the poor old man on the day of his investiture fainted during the ceremony and lay a long time as dead, as we read in the letter of Telham to the queen: The ceremonies were performed on Sunday last in the presence of the Lords, at which tyme the old man with protestations of all thankfulnesse to your Majesty, and feeling as I take it an impression of overmuch joie [we are sure it was over sorrow], had like to have resigned his pention at the Lord Justices’ table within an hour after his creation, being in all our sight dede and with great difficultie restored. The honour thus conferred brought neither peace nor good fortune to the Burkes for in little more than half a century a succession of violent or untimely deaths and family litigation brought the family to utter ruin. Sir John de Burgo, one of the purest and noblest souls that ever honoured a noble family in the next generation, risked life and limb for the very cause which his progenitors had been rewarded for opposing. He, indeed, like Louis XVI, and Sir James Desmond, had been the scapegoat for all the crimes of his ancestors. His life and martyrdom have been written. Rothe, Processus Martialis, by O’Daly, by Dominick a Rosario, Bruodin, Lib III, c20, Molanny and Hueber. This last, a Franciscan, gives a more detailed account of his martyrdom. He was put to death in the habit of St Francis, as he was a tertiary of St Francis. See a very readable and interesting life of Sir John Burke, Lord of Castle Connell, by Mrs Morgan John O’Connell in the Irish Catholic. His last words are most touching and edifying, ‘When he was urged to renounce the Catholic faith and to deny the mother of God he boldly and unhesitatingly answered, that he acknowledged no queen who did not believe in Christ, the king of heaven, and whosoever would strive to turn him from the service of both, deserved neither obedience nor respect; and whoever would act otherwise was not the servant of God but the slave of the devil.’After he was condemned to death he was carried in a cart to the place of execution outside the city of Limerick and then he asked and was allowed to be let down and to go on his knees for about a furlong to the gallows. Having commended himself to the saints with the greatest fervour, he went forward to his martyrdom as if he were going to a banquet. When Sir John was hung, some noblemen, and among them Sir Thomas Browne – the lineal ancestor of the Earl of Kenmare – petitioned the president that when the martyr’s body was taken down from the gallows, it might not be cut from limb to limb. This favour was granted and his friends and relations carried it into the city and buried it in St John’s Church about December 20th in the year 1607. 15 It is well known that there were Brownes settled in Kerry before the ancestor of the Kenmare family came over. The Brownes of Ventry, a now extinct family, are often mentioned in old county documents as existing in Kerry from the English Conquest; and it appears from this list, furnished by Churchyard, that the Brownes distinguished as the Vale-Brownes. It may possibly be that the Vial Brownes or Brownes living by the river Vial or Feale were the Earl of Desmond’s foster brothers. 16 Thos Ormond ETC, OSS. If Father Daly, OP, who condemns Owen Daniel Moriarty so unmercifully, had seriously considered the provocation he has told us that Moriarty received from the earl’s people, he would acknowledge that very few men in this world would have acted otherwise. Daly says, ‘It unfortunately happened that those who were sent by the Earl to seize the prey barbarously robbed a noble matron, whom they left naked in the field.’ Would Father Daly have acted in a different manner if his own sister had been thus treated by an earl or any one else? The truth is, Desmond was in open war with all his neighbours; preying upon all, and as a natural consequence, hunted down by all. For we find that ‘In 1581 he made a hosting into Cashell and killed four hundred innocent persons, and increasing his plunder with many steeds and other spoils’ (State Records, 1581). And in the summer of 1582 he made another successful raid into the country of his old foes, the Butlers, and left the hill on which he fought speckled with the bodies of the slain (Idem, 1582). In the autumn of this same year he made an incursion into Kerry against the O’Keeffes whom he slew in great numbers. O’Keeffe himself, ie, Art, son of Art, son of Donal, son of Art and his son Art Oge were taken prisoner by the Earl, and Hugh, another of his sons, were slain. Daly need not look farther than this to know that ‘they who live by the sword shall die by the sword’ and that ‘the blood of the innocent’ cries up to heaven for vengeance. 17 The statement was published in 1584 by the poet, Thomas Churchyard, and was intended as an example that ‘the whole realme of Ireland may see that trueth hath ever the victorie, and treason is put to shame and dishonour.’ 18 A Scourge for Rebels; Wherin are many notable services truly set out and thorowly discoursed of, with everie particular point touching the troubles of Ireland, as farre as the painfull and dutiful service of the Earle of Ormound in Sundrie sortes is manifestly knowen. Written by Thomas Churchyard (/Churchiard), Gentleman. Imprinted at London for Thomas Cadman. 1584. Doiremoire (big wood) which extended from Blennerville to Castlegregory. Bongoinder was probably a stronghold, six miles from Tralee. Bingham wrote about this date: ‘There are two notable places which the rebels give forth they will fortifie, that doe lie in the Baye of Tralee; the one is called Bongoinder and the other Kilbalahithe, which places are naturally very strong, I learn’. Bongoinder, six miles from Tralee, a very strong ground – AD 1580. Earl of Ormond, Kerry Magazine, Vol I, p98. 19 See Daltons’ Army List, Vol ii, p328. 20 This is denied by Miss Hickson. She says there is no mention of this marriage in the genealogy of the Geraldines. But these genealogies could have been made to suit the tastes of the great Geraldine House, in centuries afterwards, when the Moriartys had become the fosterers of the Geraldines. It is certainly given in the following authentic genealogy of Otho. This Thomas, surnamed the Great, who married Ellinor, daughter of The (William) Moriarty of Kerry, Iar-mond, was ancestor of the White Knight, the Knight of Glynn, the Knight of Kerry and Machenry. He died AD 1213; so that the first Irish blood that flowed in the veins of the Geraldines was that of Ellinor O’Moriarty of Kerry; both her sons, Alexander and Maurice, died without issue.