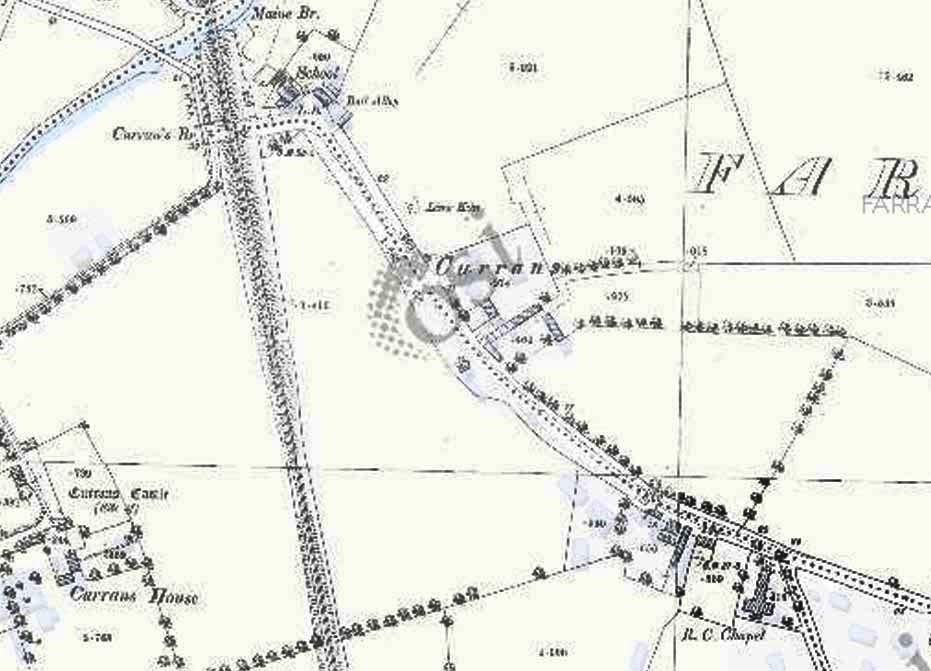

In January 1885, a correspondent of the Kerry Sentinel brought to the attention of the public the actions of the RIC in Kilfallinga, near Currans. A public meeting had been called for the purpose of establishing a branch of the Irish National League. However, on the evening before the proposed meeting, the Lord Lieutenant proclaimed it.

A large number of people from the surrounding districts, being unaware of the proclamation, arrived for the meeting including the Milltown brass band, which played through the village as far as Currans Bridge. There, they were met by a large force of police who attacked them ‘without notice in a most brutal manner’:

The Royal Irish Constabulary seized some of the instruments and attempted to smash them. Other members of this aggressive force without preface or warning brought the butt ends of their guns into unmerciful contact with the heads and bodies of the crowd.1

The following month, Kilfallinga returned to public attention with the news that a ‘serious agrarian outrage’ had occurred in the district.

On the evening of Saturday 21 February 1885, the house of John Murphy of Kilfallinga – an area within the radius of the ‘disturbed province’, Edenburn three miles to the south, and in the opposite direction, Killeentierna, scene of Arthur Herbert’s murder – had been attacked by a party of moonlighters: ‘That it was planned and carried out by members of an organised unlawful gang, there cannot be the faintest shadow of doubt.’2

John Murphy was at home that evening seated around the fire with his wife Norry, his three sons, Pat, Maurice and Denis and his daughter Margaret. Denis, who had the misfortune to be in the firing line of ‘the masked murderer’ who fired through the window, was seriously wounded in his shoulder by gunshot.3

It was however believed that John Murphy was the intended victim. John Murphy, described as an industrious and hardworking old man, had been in the periodic employ of land agent, Samuel M Hussey, at Edenburn, and at one time was caretaker of a derelict farm. As a result, his house had been attacked and fired into the previous year and the family boycotted.

Consequently, John Murphy, who assigned the reason for the attack to his fencing of the evicted farm of Mrs Tangney in order to keep himself out of the workhouse, was under the protection of the police on the night of 21st February 1885. Two constables, Dowd and Devlin, were on duty at the Murphy household.

In the nearby vicinity of John Murphy’s house was an unoccupied property, previously in the possession of the parish priest of Currans, Rev T Lynch, where a dance party was underway. Shortly after the shooting incident, a number of men in attendance, all from the vicinity of Currans and belonging to the farming class, were arrested under the Crimes Act and taken to Tralee prison. They included C Daly, D Sullivan, John Connor, James Connor, James Daly, Charles McCarthy, Edward Barry, Patrick Sullivan, Daniel Sullivan, Florence Sullivan and James Daly.

On Wednesday 25 February, however, the men, who were being represented by solicitor M J Horgan, were brought up in the jail before Heffernan Considine, Resident Magistrate, when on the evidence of District Inspector William Davis, RIC, it was concluded that they were not ‘out of their places for an improper purpose’ and they were discharged.

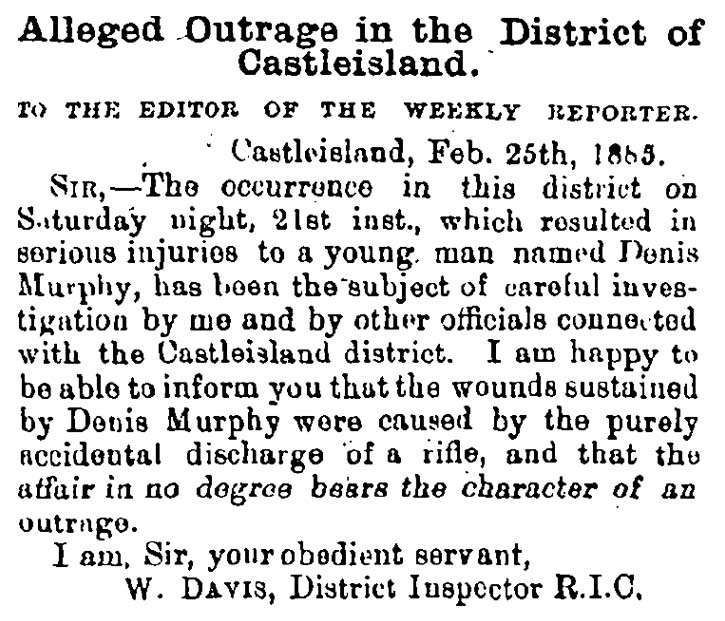

On the same day, Inspector Davis addressed a letter to the editor of the Weekly Reporter to the effect that the incident was not, after all, one of outrage, but an unfortunate accident.

The matter rested there until Sunday 8 March 1885 when Denis Murphy, about 28 years of age and unmarried, died from tetanus in Tralee infirmary. Over the next two days, an inquest was held in Tralee courthouse by Captain Thomas F Spring, district coroner, also attended by Heffernan Considine, RM.

Patrick Murphy, brother of the deceased, deposed that after the shot was fired into the house on Saturday evening, 21st February, everyone ran outside except his mother, who remained with her son Denis who had fallen down on the floor.

However, though constables Dowd and Devlin fired shots, no trace of moonlighters could be seen outside. He stated that he was under the impression the shot fired at his brother came through the window. ‘We did not discover the real fact until Mr Harrington and Charlie Daly of Currans asked us about the letter of Mr Davis’s, saying it appeared in the papers it was the policeman who accidentally fired the shot’.4

Michael Murphy, brother of the deceased, deposed that he had no reason to believe the matter an accident, and before learning about Inspector Davis’s letter, had never heard it was an accident.5

However, Constable Thomas Devlin, who had served in the force for two years, deposed that due to the inclement weather, he had been inside the Murphy house himself on the night in question and that the shot came from his own rifle under the following circumstances:

I was lately a policeman stationed at Kilfalliney; on the night of the 21st February, Constable Dowd and I were sent by the sergeant on duty to Murphy’s place; we arrived there about half past seven and went into the house immediately; we were sitting around the fire till about eight o’clock; I had with me a rifle and it was loaded with buckshot; I had it between my legs with the barrel pointing upwards in a slanting position; I could not account for how the accident occurred but the next thing I felt was the explosion of the rifle.6

The jury found that Denis Murphy died from tetanus resulting from gunshot wounds inflicted on him by the hands of Constable Devlin by accidental shooting or discharge of his rifle charged with powder and buckshot. Constable Dowd was entirely exonerated in the affair.7

House of Commons

The unusual circumstances of the case brought the matter to the House of Commons on Tuesday 10 March when Thomas Sexton, MP, asked the Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland why no investigation into the affair had been ordered.8 A writer for the Flag of Ireland remarked that ‘the government of course suppressed everything until it was dragged from them by Mr Sexton’s question in the House of Commons.9

Devlin, a native of Fethard, was subsequently arrested and conveyed to Clonmel jail.10 He was later taken before the magistrates in Castleisland and charged with improper discharge of his duty, and released on bail.11

Public Inquiry

A Public Inquiry was opened in Castleisland by H F Considine, RM, the inquiry conducted by Mr A Morphy, Crown Solicitor, on behalf of the Attorney-General, and J Roche, Solicitor, Tralee, appeared for ex-Constable Thomas Devlin.12

The charge against Devlin was under the Common Law, malfeasance or nonfeasance by any public officer in the discharge of his official duty.13 During the Inquiry, questions were raised about forged documents, claims for compensation, and levies on the rate payers. There were also suggestions of a relationship between Devlin and Margaret Murphy.14

Devlin’s trial subsequently took place in July at the Kerry Summer Assizes and he was convicted of the charges of unlawfully, wilfully and knowingly making a false report to his superior officers; making a false report with the intent to mislead the administration of justice and conspiring with several others to impede the administration of justice.

Devlin was sentenced to three months imprisonment in Tralee and was released in October 1885. He returned to Tipperary.

________

1 IE MOD/C38. The band took refuge in the home of Timothy Kennedy, Currans, for three hours. ‘Though two RMs were present, they never went to the trouble of informing the bandsmen of the proclamation. Why were they allowed to enter or play in the village if it was illegal? ... God help the Currans people while they are under the rule of the Mahdi’. See IE MOD/C38 for letter in full. 2 Kilfallinga, otherwise Kilfalliney or Kilfalney, a townland in the parish of Currans, had a small population of about 1500 and though there were a great many evicted farms in the district, no serious outrage was reported there before. The landlord was Thomas M Osborne (sometimes Usborne) Esq, JP, Cork. In 1885, the tenants met with Samuel Murray Hussey regarding their holdings: ‘In Tralee on Saturday the tenants on the Usborne Estate waited upon the agent, Mr S M Hussey, at his offices relative to the payment of their rents and the purchase of their farms under the Land Purchase Act. The Osborne Estate comprises a large portion of the estate of the parish of Currans in the confines of Castleisland … They were accompanied by their parish priest, the Rev Mr Fitzgerald, who demanded for them a reduction of 25 per cent off the judicial rents in very forcible language. There were about seventy tenants in the body’ (Kerry Evening Post, 7 October 1885). 3 Kerry Evening Post, 25 February 1885. 4 Cork Constitution, 10 March 1885. Inquest first day. Inspector Davis’s letter made no mention of who fired the shot. 5 Cork Constitution, 11 March 1885. Inquest second day. 6 Cork Constitution, 11 March 1885. The constabulary hut at Kilfalliney was erected in 1882: ‘Another police hut has been sent to Castleisland and taken to Kilfalliney near Mr Hussey’s on the evicted farm of Daniel Sullivan, tenant to Mr Osborne’ (Flag of Ireland, 9 September 1882). 7 Devlin told the coroner ‘I may never meet Dowd again and I now say that he had neither directly nor indirectly any hand in the concoction of the story that the accident was an agrarian offence. It was arranged between myself and Pat Murphy. I did not suggest to Pat that as an accident he would get no compensation. I only told him that I would be dismissed.’ Inspector Davis explained at the Public Enquiry subsequently held in Castleisland that he had preferred charges against Dowd, who had been dismissed from the force, because he had been guilty of a gross offence against his order when he entered the house, and for stating a falsehood to his sergeant by saying that he was not in the house. It was suggested that it was a mild breach of discipline, in view of the severity of the weather that night, but Davis stated he believed his dismissal had occurred because of the death of Denis Murphy. 8 Irish Times, 24 March 1885. Mr Sexton asked whether District Inspector Davis, RIC, Castleisland, swore at the inquest on the body of Denis Murphy that from the first he did not believe the case was one of outrage but that the shot had been fired from a constable’s rifle; and, if so, why he reported the case to the county inspector as being one of outrage, why he made an affidavit to procure the arrest of innocent men, and why he caused the remand of those men in custody; whether both the constables concerned persisted for some time in denying that they had been in Murphy’s house that night; whether the notes of evidence at the coroner’s inquest would be laid upon the table; whether his attention had been called to the remarks of the Lord Chief Baron at Tralee on the 18th inst in his charge to the grand jury of Kerry who declared that, apart from the question whether Murphy was wounded by accident, there could be no doubt that a very grave crime against the administration of justice had been committed; that there was nothing more calculated to shake confidence in the administration of justice than that members of the constabulary force should lead themselves to what had been done in that melancholy case; and that he regretted, and deemed it unfortunate, that no bill had been presented to the grand jury in reference to the matter so that the most searching investigation should be given to what appeared to him to be a very grievous misdemeanour of endeavouring to defeat, delay or impede the administration of justice; why the Crown did not present to the Kerry Grand Jury a bill in respect of this offence; and what would now be done in the case? Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman replied: District Inspector Davis did not swear at the inquest that from the first he did not believe the case was one of outrage. He stated that the surroundings did not strike him as being those of a genuine outrage. From the report of the constables, which was positive and unequivocal, he, in the discharge of his duty, reported to the county inspector the case as communicated to him. He afterwards, from personal examination, satisfied himself that the case was not one of outrage. He did not make an affidavit to procure an arrest, nor did he cause any remand. The arrest was made by constables in his absence and the remand was on their information. The constables did for some time persist in denying that they had been in Murphy’s house and this was one of the reasons for their dismissal. There is no objection to lay upon the table the notes of the evidence at the inquest. The Lord Chief Baron did express himself to the effect stated. The charge of manslaughter was only dismissed on March 10th and there was not then leave to present a further charge to the grand jury at Tralee. A prosecution of another kind will now be instituted. 9 Flag of Ireland, 14 March 1885. 10 ‘Devlin is a native of this place and his brother Bernard is very well known and respected in this locality’ (Freeman’s Journal, 27 March 1885). 11 Devlin was staying at Fethard but was re-arrested in Cork on suspicion of being about to leave the country for America (which he vehemently denied). He was subsequently held in jail pending his trial. 12 Cork Constitution, 31 March 1885. 13 ‘That the defendant, Thomas Devlin, late a constable in the Royal Irish Constabulary force, wilfully misbehaved himself in his office as constable by wilfully making a false statement that a certain house in which a man named John Murphy resided had been fired into on the night of the 21st February 1885 at Kilfalliney in the district of Castleisland.’ 14 Sergeant John Healy deposed that he was stationed at Kilfalliney on 21st February in charge of a hut and at 7pm, sent Devlin and Constable Dowd to John Murphy’s of Kilfalliney where they were instructed to remain from 7.30 pm until 10 pm, and to not enter the house. At 8.30 pm Devlin reported that a shot had been fired into John Murphy’s house through the back window. The next morning, Sergeant Healy and his patrol arrested eight men and charged them with being concerned in the outrage; they were escorted prisoners to Castleisland. An official document called the ‘guard’s diary’ kept at the hut had the following entries made that night by Devlin in Devlin’s hand: ‘At half-past eight Constable Devlin reported at the barracks that two shots were fired at John Murphy’s, injuring Denis Murphy; at 8.30 Sergeant Healy and two constables proceeded to the scene of the occurrence.' It was asked at the inquiry that only for Devlin coming forward and telling the truth, the Murphys would have a huge claim of compensation under the Crimes Act? Do you not think that the ratepayers of Currans owe a debt of gratitude to Devlin? … Even after Devlin had admitted the truth about the matter, were the Murphys still persisting that it was an agrarian outrage? Inspector Davis stated that the matter was reported to him about one o’clock and he attended the scene at about one thirty; the surroundings did not strike him as being a genuine outrage and when the pellets were given to him by Dr Brosnan he was perfectly assured that it was done by one of the policemen’s rifles; ‘in all the outrages that occurred in Castleisland, he never saw one of those pellets before’.