While Bourns, the engineer, explained to his Foreman, By his physics, the centring of the O’Connell Bridge, Said this King, and that Queen-post would ever support man, The O’Connell without ever introducing a wedge.[1]

There was considerable excitement in Castleisland in late 1831 as the new O’Connell Bridge neared completion:

The bridge is a large one, consisting of three thirty-feet arches, which are now nearly finished. It is called the ‘O’Connell’ and if attending to equilibration and permanency, it deserves the name. We learn that there will be held, annually, at the bridge, what is called a Pattern on the birth day of O’Connell.[2]

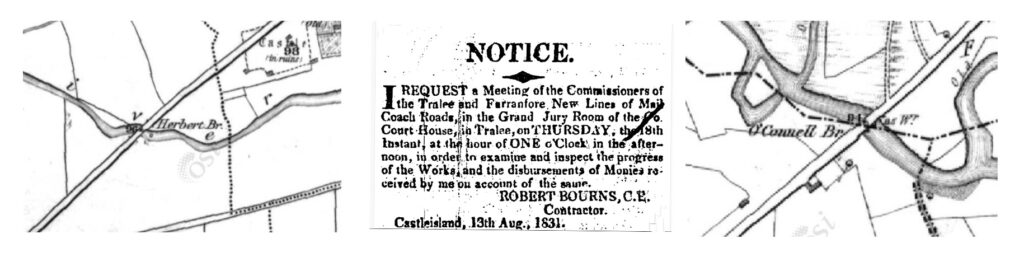

The bridge, situated on a new line of road that led from Castleisland to Farranfore, was built by Civil Engineer Robert Bourns who had completed a second bridge, the Herbert Bridge, closer to the town of Castleisland.[3] Bourns, who had been working in Kerry for two years, was ‘of long and tried experience in the making of roads and bridges.’[4] He had improved the Galway and Sligo mail-coach roads and the great Northern mail-coach road from Dublin to Ashbourne, Drogheda, Slane and thence to Carrickmacross.[5]

Road Building Project in Kerry 1822-1828

The road building project in the south had commenced about ten years before O’Connell Bridge was completed. In 1822, Robert Bourns had presented a memorial to Earl Talbot, Lord Lieutenant, at Dublin Castle in favour of road building in the south.[6] Richard Griffith was the civil engineer employed to direct the project.[7]

Griffith described the progress made from 1822 to 1828 in the ‘Southern District’:

The Southern District comprehends the counties of Cork, Limerick and Kerry; and the public roads which I have commenced in it, by order of the Irish government, have been confined to mountainous or uncultivated tracts hitherto inaccessible, or nearly so, and which, in periods of disturbance, had been the rendezvous and asylum of rebels, murderers and robbers.[8]

Griffith, observing that the district was formerly ‘the seat of the rebellion of the Earl of Desmond in the reign of Queen Elizabeth’ and that during the Whiteboy insurrection in the year 1821 ‘there was no road in the district passable for horsemen in wet weather,’ outlined the area under his direction:

The principal district of the kind through which roads have been made is bounded on the north by the river Shannon – on the south by the river Blackwater – on the west by the fertile country extending from Tarbert on the river Shannon by Listowel and Castleisland, to Killarney, in the county of Kerry – and on the east by a line drawn from Foynes, on the river Shannon, in a southern direction, by Newcastle to the river Blackwater, near the town of Kanturk, in the county of Cork. The extent of hilly country comprehended within the above-mentioned limits amounts to upwards of 900 square miles, in the interior of which there is but one small village called Abbeyfeale, and no resident landed proprietor or Protestant clergyman.[9]

‘The object of the government was to open the country so as to render it generally accessible,’ said Griffith, ‘and for this purpose three main lines of road were determined on’:

One to run nearly in a north and south direction from the village of Newmarket in the county Cork, to Listowel, in the county of Kerry, a distance of 32 miles; a second, at right angles to the first, and nearly in an east and west direction, from Newcastle, in the county of Limerick, by the small village of Abbeyfeale, to the town of Castleisland in the county of Kerry, a distance of 29 miles; and a third also in an east and west direction twenty miles to the south of the second, from Newmarket in the county of Cork for a length of fourteen miles towards Charleville in the same county, making a total of 75½ miles of new road.[10]

Griffith recalled the response to the building project at its commencement:

People flocked from all quarters, seeking employment at any rate which might be offered; their general appearance bespoke extreme poverty, their looks were haggard, and their clothing wretched; they rarely possessed tools or implements of husbandry, beyond a small ill-made spade, and, as might be expected under such circumstances, nearly the whole face of the country was unimproved, and in a state of nature. But since the completion of the roads, rapid strides have been made towards cultivation and improvement.[11]

He gave account of the improvements:

Upwards of sixty new lime kilns have been built for the purpose of burning lime, for agriculture, within the last two years; carts, ploughs, and harrows of superior construction and other agricultural implements have become common, new houses of a better class have been built, or are building in great numbers in the vicinity of the new roads, and also in the villages of Newmarket, Castleisland, and Abbeyfeale; new inclosures of mountain farms are being made in every direction, and this country, which within the last seven years was the theatre of lawless outrage, and the residence of what might be termed the rebel army, has become perfectly tranquil, and exhibits a scene of industry and exertion at once pleasing and remarkable.[12]

Griffith described how the success of the project had hampered him in sourcing labour, and how the price of land had increased considerably. He also observed that the new roads had improved communication with the markets in the cities of Cork and Limerick and had a remarkable impact on agricultural produce.[13]

‘No road passable for horsemen’

However, there was still work to be done:

The improvements do not extend to the whole of the mountain district situated between the river Blackwater; there remains a considerable portion, extending northward from the river Blackwater to a line drawn between the towns of Castleisland and Newmarket, comprehending an area of about 200 square miles or 128,000 acres, in which there is no road passable for horsemen during the winter months.[14]

‘As expressed in a former report,’ he wrote, ‘I have long contemplated the propriety of making a road through this neglected district, and of opening it to the markets of Cork and Mallow. It would complete the principal object for which I was sent to the Southern District – namely, the forming new roads through these mountains, and rendering them accessible in every part’:

I am of opinion that the proposed road should commence at Castle-island and proceed eastward through the mountains, and through the collieries of Clonbanin, Drominagh, Dromagh, and Coolclough, join the new road now making to Cork through the Bogra mountains at Clonmeen bridge, over the river Blackwater. This road, if completed, would open a direct communication from Tralee and Castleisland to the city of Cork, which is the best market, and would shorten the road between Tralee and Cork 14 statute miles, and between Castle-island and Cork 22 miles; the present distance from Tralee to Cork by Killarney being 76 statute miles, while the proposed road will be but 62 miles. This road is of the utmost importance to the future improvement of the country … The length of the new road will be about 23 statute miles, and the expense about £11,000.[15]

Castleisland Road Building 1829-1833

In 1825, the new road from Limerick to Castleisland was in progress:

The new line of road now in considerable forwardness from Limerick to Castleisland will be continued direct through Milltown to Valentia for which government has promised assistance. A handsome hotel, at the expense of £5,000 is to be erected at Valentia by the Steam Navigation Company.[16]

In 1829, plans and specifications for the mail coach road to Tralee by way of Castleisland were approved.[17] In 1831, the constabulary at Castleisland issued Robert Bourns with a warrant ‘to protect him in the execution of his labour’ on the new road from Castleisland to Killarney after objection was made to the use of a stone quarry.[18]

In August 1831, with O’Connell Bridge and Herbert Bridge under his belt, Robert Bourns called for a meeting of the road commissioners at Tralee Court House to inspect progress and settle accounts.[19]

By February 1833, work was underway on the road between Castleisland and Milltown. Mr Bourns had 600 men under his charge:

Mr Boyan (sic) is at present employed as Mr Griffith’s chief assistant on forty-two miles of new roads in the counties of Cork and Kerry between Castle-Island and Milltown. He has at present six hundred labourers each day at work, and in the beginning of the next month intends to employ forty stone-cutters.[20]

However, in March, the month following, it was announced that Robert Bourns had died at Benner’s Hotel in Tralee.[21]

Little of a biographical nature is known about Robert Bourns, though there is a suggestion he was a native of Co Mayo.[22] Castleisland District Heritage would welcome any further information about him.

In the meantime, his name endures with The Liberator and Herbert at the two fine structural bridges he left in Castleisland.[23]

Road Building Project post-1833

In the weeks following the death of Robert Bourns, news reached Castleisland that ‘a numerous stud of horses from Mr Bianconi’s concern’ had passed on to the Kerry line of road, to convey the mails between Limerick, Tralee and the intermediate towns.

It was remarked that this was ‘in place of Mr Bourne.’[24] The ‘Mr Bourne’ in this instance was the noted and leading mail coach proprietor William Hawker Bourne (sometimes given as William Hawkins Bourne) of Bourne & Co who operated the Dublin Limerick mail coach service with his brother Richard Bourne.[25]

Bourne, of Terenure House, Dublin, was described as ‘the original proprietor of mail and stage coaches in Ireland’:

Few in his time had greater opportunities and none turned them in every instance to more advantage for the improvement of his native country and the comfort as well as benefit of its inhabitants. His life was constantly devoted to measures of public utility and well may he be esteemed a practical patriot and philanthropist. He is was that first established a Mail Coach between this city and Dublin; while by pushing the sphere of his operations, he also opened new and unexplored sources of profit to the merchant and agriculturist throughout the South of Ireland by forming splendid roads and providing safe and expeditious conveyances on various lines of route. His large establishment gave employment to a vast number of persons.[26]

William Hawker Bourne died at Piccadilly in London on 22 September 1837 and was laid to rest in the family vault at Mount Jerome.[27]

The deaths of Robert Bourns and William Bourne marked a revolutionary period of dynamic change in the movement of people locally and nationally.

To the Bridge They Resort

A cottager present (to the bridge they resort), Told his neighbours the Engineer’s tale, “That the King and the Queen would O’Connell support,” Arragh the jewel he never did fail.[28]

It was hoped that with the opening of O’Connell Bridge in 1831, a pattern would be held there annually to celebrate the birthday of the Liberator. Almost two centuries have passed and events that may have taken place there before and after the Famine are no longer recalled.

New roads and fast cars mean that the bridge today is hardly noticed. But off the beaten track a few steps below the fast moving road, the beauty of the bridge remains just as described during its year of construction:

The new bridge over the river Brown-flesk, on the new Mail-Coach road from Limerick to Killarney, which is now in progress of building by Mr Robert Bourns, Civil Engineer, we have heard, does that gentleman great credit. The bridge is a large one, consisting of three thirty-feet arches, which are now nearly finished. It is called the ‘O’Connell’ and if attending to equilibration and permanency, it deserves the name.

This year (2025) marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Daniel O’Connell. In Ireland, the memory of the great man will be celebrated nationally, and it would be a worthy tribute if a blessing took place at the fine O’Connell Bridge in Kerry.

____________________

[1] ‘Kerry New Mail-Coach Roads,’ Freeman’s Journal, 3 December 1831. [2] Tralee Mercury, 19 November 1831. ‘The new bridge over the river Brown-flesk, on the new Mail-Coach road from Limerick to Killarney, which is now in progress of building by Mr Robert Bourns, Civil Engineer, we have heard, does that gentleman great credit. The bridge is a large one, consisting of three thirty-feet arches, which are now nearly finished. It is called the ‘O’Connell’ and if attending to equilibration and permanency, it deserves the name. We learn that there will be held, annually, at the bridge, what is called a Pattern (quere patron?) on the birth day of O’Connell. On this new line of road Mr Bourns has built another large bridge over the river Mang, which does him equal credit; this bridge is called the ‘Herbert.’ His new roads also (a distance of about twelve miles) are executed in a scientific manner, and will be travelled on next spring. We will not say they will be macadamised. No, we must not go to the other side of the water for names – but we will say that they will be Bournised; for he is, we understand, a gentleman of long and tried experience in the making of roads and bridges. He it was that improved the Galway and Sligo mail-coach roads, as also the great Northern mail-coach road from Dublin to Ashbourne, Drogheda, Slane and thence to Carrickmacross. He is now in Kerry, where he has been for nearly two years. We are glad to state that he is recovered from his recent illness.’ [3] Ibid. ‘On this new line of road Mr Bourns has built another large bridge over the river Mang, which does him equal credit; this bridge is called the ‘Herbert’.’ [4] In early 1829, it was reported that ‘Mr Bournes, civil engineer, has been for the last fortnight in the vicinity of Abbeyfeale, surveying a new line from Castle Island to Tralee, which will bring Limerick nearer by fifteen miles; the line is a beautiful flat, and the present line is bad, narrow, and hilly. Mr Bournes is an eminent engineer, having laid out a vast number of roads in the north’ (Freeman’s Journal, 3 February 1829). In November 1830, Bourns examined the Ashbourne Turnpike Road in Finglas at which time he remarked, ‘I have been engaged for upwards of twenty years in making and repairing roads in various parts of the kingdom’ (Saunders’s News-Letter, 27 November 1830). [5] Tralee Mercury, 19 November 1831. [6] National Archives of Ireland reference CSO/RP/1822/1977. [7] Further reference to Sir Richard Griffith (1784-1878) at http://www.odonohoearchive.com/sir-richard-griffith-in-castleisland/ [8] Chutes Western Herald 7 May 1829. ‘Roads in Ireland.’ [9] Chutes Western Herald 7 May 1829. ‘Roads in Ireland.’ [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Ibid. [13] Ibid. [14] Ibid. [15] Chutes Western Herald 7 May 1829. The report in full: ‘Roads in Ireland. Report of the Southern District of Ireland, containing a statement of the progress made on the several roads carried on at the public expense in that District, under the orders of his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant – Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed, 10th April 1829. To the Right Honourable Lord Francis Leveson Gower. My Lord – Herewith I have the honour to submit to you, for the information of his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant, a general statement of the amount expended by me on the public works in the Southern District in Ireland during the year 1828; and in addition, I think it my duty to describe the progress that has been made towards the completion of the several roads that have been commenced under my direction in that district since the year 1823. As already stated by me in former reports, the Southern District comprehends the counties of Cork, Limerick and Kerry; and the public roads which I have commenced in it, by order of the Irish government, have been confined to mountainous or uncultivated tracts hitherto inaccessible, or nearly so, and which, in periods of disturbance, had been the rendezvous and asylum of rebels, murderers and robbers. The principal district of the kind through which roads have been made is bounded on the north by the river Shannon – on the south by the river Blackwater – on the west by the fertile country extending from Tarbert on the river Shannon by Listowel and Castleisland, to Killarney, in the county of Kerry – and on the east by a line drawn from Foynes, on the river Shannon, in a southern direction, by Newcastle to the river Blackwater, near the town of Kanturk, in the county of Cork. The extent of hilly country comprehended within the above-mentioned limits amounts to upwards of 900 square miles, in the interior of which there is but one small village called Abbeyfeale, and no resident landed proprietor or Protestant clergyman. The district is hilly but not mountainous, the surface is generally of a moory or clayey nature, which is easily fertilized when cultivate and manured with lime. The inhabitants, who is some parts are very numerous, are poor, ignorant, and in many cases of turbulent habits and manners. This district had been formerly the seat the of rebellion of the Earl of Desmond in the reign of Queen Elizabeth; and it is remarkable that the only passes ever made through it were effected at the instance and expense of the British government immediately subsequent to that rebellion. These passes, or roads, were laid out in straight lines without any reference to the nature of the country and ran directly over hill and valley, from one military point to another. In many cases the inclination in ascending the hills amounted to one foot perpendicular to four feet horizontal, and an ascent of one foot in six was a common occurrence; this circumstance, together with the very imperfect manner in which the bridges had been built, was the cause of these roads being neglected by the Grand Juries of the surrounding counties; and in consequence, during the Whiteboy insurrection in the year 1821, there was no road in the district passable for horsemen in wet weather. It now becomes my pleasing task to describe the improvements which have been effected since the month of September 1822, when I first commenced laying out the new roads through this neglected district. The object of the government was to open the country so as to render it generally accessible, and for this purpose three main lines of road were determined on: one to run nearly in a north and south direction from the village of Newmarket in the county Cork, to Listowel, in the county of Kerry, a distance of 32 miles; a second, at right angles to the first, and nearly in an east and west direction, from Newcastle, in the county of Limerick, by the small village of Abbeyfeale, to the town of Castleisland in the county of Kerry, a distance of 29 miles; and a third also in an east and west direction twenty miles to the south of the second, from Newmarket in the county of Cork for a length of fourteen miles towards Charleville in the same county, making a total of 75½ miles of new road. With the exception of eight miles at the northern or Listowel extremity of the first mentioned road, the whole of the new roads have been completed, and are now open to the public, some parts for three years and some for two years; and a very considerable improvement has already taken place in the vicinity of the roads, both in the industry of the inhabitants and the appearance of the country. At the commencement of the works the people flocked to them from all quarters, seeking employment at any rate which might be offered; their general appearance bespoke extreme poverty, their looks were haggard, and their clothing wretched; they rarely possessed tools or implements of husbandry, beyond a small ill-made spade, and, as might be expected under such circumstances, nearly the whole face of the country was unimproved, and in a state of nature. But since the completion of the roads, rapid strides have been made towards cultivation and improvement. Upwards of sixty new lime kilns have been built for the purpose of burning lime, for agriculture, within the last two years; carts, ploughs, and harrows of superior construction and other agricultural implements have become common, new houses of a better class have been built, or are building in great numbers in the vicinity of the new roads, and also in the villages of Newmarket, Castleisland, and Abbeyfeale; new inclosures of mountain farms are being made in every direction, and this country, which within the last seven years was the theatre of lawless outrage, and the residence of what might be termed the rebel army, has become perfectly tranquil, and exhibits a scene of industry and exertion at once pleasing and remarkable. To the credit of the inhabitants, I must say that a large portion of the money received by them for labour on the roads has been husbanded with care, and subsequently laid out in building substantial houses, and in the purchase of cattle and implements of husbandry; and numerous examples might be adduced of poor labourers, possessing neither money, houses, or lands, when first employed on the public roads, who, within the last year have been able to take farms, build houses, and stock their lands with cows and young cattle so that in many instances those who six years ago were the labouring servants of small farmers, have now become more independent than their former masters. The extension of industry and farming employment among the inhabitants was sensibly felt by me during the last two years, by creating a difficulty in procuring labourers to work on those parts of the roads which were not completed. At certain periods of the year no price could tempt new landholders to leave their farms, and in consequence, during the last summer I was obliged to invite strangers from considerable distances and at advanced prices to work on the roads, and purchase horses and carts for the transport of stone and materials, as none could be procured for hire, every farming horse in the country being most usefully employed in drawing lime or limestone to manure the land. This circumstance has considerably increased the expense of completing the new roads and has caused an additional expenditure in maintaining those parts first completed, as the moment any portion of a road was open, passages were made to join it by the neighbouring farmers, and deep ruts were soon formed by strings of loaded lime carts. As might be expected from the foregoing statement, the value of land has much increased in the interior of the district and in some cases more than double the former rent has been offered by tenants whose leases had expired, and new farms have been let at comparatively high rents; but several of the landed proprietors have seconded the exertions of their tenants, and have made large allowances for permanent improvements, such as building, fencing, draining and liming. The advantage of the new roads has not been confined solely to the improvement of the interior of the district; the surrounding fertile country has also been materially benefited by the opening, level, and direct lines of communication through the unimproved country to the cities of Cork and Limerick which are the great marts for all kinds of agricultural produce. Thus the new road from Newmarket to Listowel will diminish the distance, by a good road between the latter place and the city of Cork, 36 statute miles; the distance between Listowel and Cork by the present road through Tralee and Killarney being 102 miles, while by the new road it is but 66 miles. In the same manner the distance by a good road between Limerick and Killarney will be diminished 29 miles; the present road by Tarbert and Listowel being 99 miles in length, while by the new road it is but 69 miles. The improvements above described, which are attributable to the new roads, do not extend to the whole of the mountain district situated between the river Blackwater; there remains a considerable portion, extending northward from the river Blackwater to a line drawn between the towns of Castleisland and Newmarket, comprehending an area of about 200 square miles or 128,000 acres, in which there is no road passable for horsemen during the winter months. As expressed in a former report, I have long contemplated the propriety of making a road through this neglected district, and of opening it to the markets of Cork and Mallow. It would complete the principal object for which I was sent to the Southern District – namely, the forming new roads through these mountains, and rendering them accessible in every part. I am of opinion that the proposed road should commence at Castle-island and proceed eastward through the mountains, and through the collieries of Clonbanin, Drominagh, Dromagh, and Coolclough, join the new road now making to Cork through the Bogra mountains at Clonmeen bridge, over the river Blackwater. This road, if completed, would open a direct communication from Tralee and Castleisland to the city of Cork, which is the best market, and would shorten the road between Tralee and Cork 14 statute miles, and between Castle-island and Cork 22 miles; the present distance from Tralee to Cork by Killarney being 76 statute miles, while the proposed road will be but 62 miles. This road is of the utmost importance to the future improvement of the country. It would pass through or very close to the whole of the valuable coal and culm collieries of the Southern District, and afford an easy communication to the surrounding country, many parts of which are in the greatest want of fuel for domestic purposes, and for burning lime, the only manure there used for corn crops. This road would also produce a most beneficial effect on the agriculture of the country through which it passes. There are limestone quarries at both extremities, and the whole intervening country is covered by a stiff cold clay soil, which when manured by lime is susceptible to great improvement, and capable of producing excellent crops of oats, potatoes and flax. At present, from want of roads, no limestone can be drawn into the country, and consequently the land remains untilled, and the inhabitants are slothful, wretched and discontented. For these reasons I should strongly recommend that a survey be made of the proposed line, and that one half of the sum required to complete this road should be defrayed out of the Consolidated Fund under the 1st George IV c 81. The length of the new road will be about 23 statute miles, and the expense about £11,000. In addition to the roads already mentioned, several others have been commenced and completed under my direction in different parts of the Southern District, viz: Road from Skibbereen to the harbour of Crookhaven, on the south-west coast of the county of Cork, 23 miles; New road from the city of Limerick Askeaton, to Robertstown, being a portion of the road from Limerick by Tarbert to Tralee, length of new road 16 miles; Road from Clonmeen bridge over the river Blackwater, through the Bogra mountains, to the city of Cork, part completed by Mr Griffith, 14 miles; Road from Macroom in the county of Cork to Glanflesk in the county of Kerry, 10 miles; Road connecting the towns of Bantry and Skibbereen in the county of Cork, 8 miles; New road into Bandon 1 miles 1 furlong; New road from the town of Clonakilty in the county of Cork to the fishery pier at Ring, 2 miles 2 furlongs; Road from Timoleague along the sea shore to the pier at Courtmacsherry in the county of Cork, 3 miles 3 furlongs, Total 89 miles 6 furlongs. The situation and importance of the whole of the above-mentioned roads have already been described in my reports for the years 1823 and 1824; it is therefore unnecessary to describe them in this place. I shall only add that their completion has given an impetus to agricultural exertion quite unexampled in the mountainous districts of the south of Ireland, and several have become leading lines of communication between distant parts of the country particularly the new road from Limerick by Askeaton to Tralee, and that from Cork, by Macroom to Glanflesk, to Killarney and Kenmare. This latter road has reduced the travelling distance from Cork to Killarney five miles, and from Cork to Kenmare nineteen miles. The foregoing statement comprehends the whole of the roads completed under my direction in the Southern District. The three roads first described, situated in the mountain tract between the river Shannon and the river Blackwater, total length of new road, 74 miles 4 furlongs; Detached roads situated in different parts of the Southern District, 89 miles 6 furlongs; Total length of new roads completed by Mr Griffith 105 miles 2 furlongs. In my report for the year 1824, I gave it as my opinion that to complete the communication between Tarbert on the river Shannon and Skibbereen on the southern coast of the county of Cork, a distance of 84 miles, I should recommend the opening of a new line of road across the mountain ridge which separates Bantry Bay from the river Kenmare, over which no road passable for carriages has yet been made. From a careful examination of the country, I was enabled to lay out a very favourable line of road between the towns of Bantry and Kenmare, which I would strongly recommend to his Excellency’s consideration, and that one half of the sum required for its completion should be granted out of the Consolidated Fund, under the Act of the 4th Geo IV c42, and the remainder defrayed by the Grand Juries of the counties of Cork and Kerry. I have the honor &c Richard Griffith. Statement of Cash received by Richard Griffith, Engineer, on account of the Public Works in the Southern District between the 1st of January and the 31st of December 1828. July received from the Treasury £1,999 13 10; October received from the Treasury £1,999 13 10; By cash due to balance this account £4 4 3½. Total £4003 10 11½. General Abstract of Payments &c made on the several roads in the Southern District under the direction of Richard Griffith, Civil Engineer, between the 1st of January and the 31st of December 1828. Cash expended in completing new road from Newmarket to Abbeyfeale £1,845 13s 2d; Cash expended in completing new road from Abbeyfeale to Newcastle £103 6s 7d; Cash expended in completing new road from Abbeyfeale to Castleisland £235 6s 9d; Cash expended in completing new road from Listowel Road £231 8s 11½d; Forage of horses employed on the roads £377 1s 2d; Carpentry £33 1s 5d; Timber and carriage £4 8s 6d; Expenses incurred on sundry road surveys £57 16s 4d; Carriage of road surveys £2 19s 10d; Office stationery & postage £63 16s 1½d; Salary of Resident Engineer including clerks, paymasters & sundries £855 8s 9d; Total at Abbeyfeale £3,470 8s 6d; Cash expended in completing new road from Macroom to Glanflesk £202 10s 0d; Cash expended repairing Askeaton road £65 17s 0½d; General sundries £264 15s 5d. total £4,003 10 11½d.’ Griffith was still calling for the building of this road in 1831. The following report from Chutes Western Herald, 20 August 1831: ‘Proposed Roads in Ireland from Mr Griffith’s Report. Though not expressly called upon by order of the house to recommend any new lines of road, which it would appear to be advisable to make, either at the expense of the government or the country in which they are situated, still I think it right to submit to the house that the object for which I was sent down to the south west of Ireland, namely, the opening of new lines of road through the hitherto inaccessible tracts of mountain country, and rendering them accessible in every part, is still incomplete, in as much as several lines of road of great importance to the future improvement and tranquillity of the country have not yet been commenced … there still remains a considerable portion of the country extending northward from the river Blackwater line drawn between the towns of Castle Island and Newmarket comprehending an area of about 200 square miles or 121,000 acres in which there is no road passable for horsemen during the winter months. I have long contemplated the propriety of making a road through this neglected district, and of opening it to the markets of Cork and Mallow. The new road should commence at the town of Castle Island, and proceed eastward through the mountains, and passing the collieries of Clanbarium, Drominagh, Dromagh and Coolclogh, join the new lines of road to Cork, through the Bogra Mountains at Cloneen Bridge over the River Blackwater. This road if completed would open a direct communication from Tralee and Castle Island to the City of Cork, which is the best market, and would shorten the road between Tralee and Cork 14 miles and between Castle Island and Cork 20 miles – the present distance from Tralee to Cork by Killarney being 76 miles while by the proposed road it will be but 62. This road is of the utmost importance to the future improvement of the country. It would pass through or very close to the whole of the valuable coal and culm collieries of the southern district and afford an easy accommodation to the greatest want of fuel for domestic purposes, and for burning lime for manure. It would also produce a most beneficial effect on the agriculture of the country through which is would pass. There are limestone quarries at both extremities and the whole of the intervening country is covered by a stiff clay soil which, when manured by lime is susceptible of great improvement and capable of producing excellent crops of oats and potatoes; at present from want of roads no limestone can be drawn into the mountain country, and consequently the land remains untilled, and the inhabitants wretched, slothful and discontented. The length of the proposed new road from Castle Island to Cloneen Bridge over the River Blackwater is about 26 miles. Observations similar to the foregoing are applicable to the opening of the proposed lines of road from Killarney to Mallow along the north bank of the River Blackwater and a considerable portion of the road from Castle Island to Cork where it passes along the valley of that river would be common to both roads. In fact, to complete this second line of communication would only require 13 miles of new road which added to 26 miles required for the completion of the road from Tralee to Cork, would make a total of about 39 miles of new road. No detailed survey has at yet been made of either of these lines of road but from my knowledge of the country, I am of opinion that the distances would not exceed those I have mentioned and that in round numbers the expense of completing them would be about £20,000. In addition to the foregoing, I should recommend that a new line of road be made across the mountain ridge which separates Bantry Bay from the River Kenmare in the counties of Cork and Kerry. At present there is no direct road (at least none deserving the name) between these points; and that traveller, in proceeding from Kenmare to Bantry, is now obliged to go round by Macroom, a distance of nearly 60 miles, while in a direct line, the distance between those points is not more than 19 miles. Having made a careful examination of the country, I discovered a very favourable line for a new road between Kenmare and Bantry on which there would be no steep ascent on any part, and which line I strongly recommend for adoption. It would not only open a direct communication between the important harbours of Kenmare and Bantry, but complete the line of communication along the coast between Tarbert on the River Shannon and Skibbereen and Castle Haven on the south coast of the County of Cork.’ [16] Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 23 July 1825. [17] Tralee Mercury, 25 February 1829. ‘A Special Sessions was held on Monday last, at the County Court House in Tralee, for the purpose of investigating the Presentments preparatory to the Assizes. The magistrates who qualified for the occasion were Richard Meredith Esq of Dicksgrove, Chairman, Captain Bowles, McGillycuddy of the Reeks, Mr Blennerhassett, Mr Rowland Eagar, Mr Chute of Chutehall. Several other magistrates also attended. At present we can only notice the Presentment for the completion of the Mail Coach road from Limerick to Tralee by way of Castleisland. The amount presented for was £2,700. Mr Blennerhassett of Ballyseedy was the Overseer, and Mr Bourne, the Coach Proprietor, was the Civil Engineer. The plans and specifications were examined, and the Presentment was approved of by the magistrates.’ A presentment for completion of the Mail Coach Road from Limerick to Tralee through Castleisland has been approved of at Tralee Special Sessions for the estimate of 2500l Overseer Arthur Blennerhasset Esq; Civil Engineer Mr Bourne, Limerick (Limerick Chronicle 25 Feb 1829). A presentment is to be applied for at the ensuing Assizes of Tralee for completing the mail coach road from Castleisland to Tralee. A sum of £2000 will be necessary to complete this useful work. Mr Bourne of Limerick will be the engineer (Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier, 5 March 1829). His Lordship next adverted at considerable length to the Presentment for completing the Mail Coach Road from Limerick through Castleisland to Tralee and pointed out the great advantages as to time in the communications with Dublin and the other parts of the Kingdom which could on this plan be encompassed at a trifling expense (Chutes Western Herald, 23 March 1829). [18] CSO/RP/OR/1831/1012 File of documents arising from the disputed use of the police constabulary in protecting the contractor of the new mail coach road from Castleisland to Killarney … includes letter from Henry Brownrigg Sub-Inspector Tralee to Major William Miller Inspector General of Police in Munster about a complaint by a man named Brennan who says his men were prevented from making use of a stone quarry between Killarney and Castleisland by the police. Includes copy of warrant giving authority to Robert Bournes, road contractor, ‘to call on the constabulary to protect him in the execution of his labour’ issued to the police at Castleisland and signed by J Herbert, John O’Connell and James O’Connell, commissioners of the mail coach road from Tralee to Castleisland and the section from Farranfore to Killarney (March to December 1831). ‘It is contemplated to run a coach from Limerick to Killarney as soon as the road from Castleisland to Killarney is completed. This coach may bring the mails into Killarney 12 hours earlier than they are received there at present. Mr Bourne, the Mail coach proprietor, has been in Killarney endeavouring to forward this measure’ (Kerry Evening Post, 3 January 1829). [19] Notice: I request a meeting of the Commissioners of the Tralee and Farranfore New Lines of Mail Coach Roads in the Grand Jury Room of the Co Court House in Tralee on Thursday the 18th instant, at the hour of ONE O’Clock in the afternoon, in order to examine and inspect the progress of the Works, and the disbursements of Monies received by me on account of the same. Robert Bourns, CE, Contractor, Castleisland, 13 August 1831 Other transactions included a Presentment in March 1831: Robert Bournes, Edmond Madden and Dennis Callaghan for widening the bridge on the road from Tralee to Castleisland between Knockeen and Castleisland on Dorlogue … same for widening the bridge on the road from Tralee to Castleisland between Knockeen and Castleisland on Castleisland Menus all approved (Tralee Mercury 9 March 1831) … In September 1831: £26 15s 0d granted. [20] Limerick Chronicle, 13 February 1833. ‘Mr Bogan {sic} is at present employed as Mr Griffith’s chief assistant on forty-two miles of new roads in the counties of Cork and Kerry between Castle-Island and Milltown’ (Mayo Constitution, 18 February 1833). [21] No age, or cause of death was given in the death notice though Cholera was prevalent in the town at the time. [22] ‘In Tralee, Robert Bourne Esq late of Mayo, Contractor and Superintendent of the new line of road between Tralee, Castleisland, and Limerick’ (Limerick Chronicle, 16 March 1833). Other notices observed his association with road building at Ashbourne: ‘Died yesterday at Benner’s Hotel in this town Robert Bourne Esq late of Ashbourne county Meath, Civil Engineer and Contractor for the new Mail Coach road in this county’ (Chutes Western Herald, 14 March 1833). ‘On Wednesday [13] March 1833, at Bennet’s Hotel, Tralee, Robert Bourns Esq, late of Ashbourne, county Meath, Civil Engineer, and Contractor for the new Mail Coach road in the county Kerry’ (Dublin Observer, 23 March 1833). The death of another civil engineer occurred in Tralee in the same year: ‘Died on Wednesday in Nelson street, Mr James Simpson Civil Engineer, a truly upright and respectable member of society leaving an afflicted widow and large young family to mourn his premature demise’ (Tralee Mercury 30 November 1833). The premature death of Alexander had occurred the year before: ‘Died in Marlborough Street, Dublin, aged forty nine years, Alexander Nimmo Esq, Civil Engineer, MRIA, MGSL’ (Chutes Western Herald, 26 January 1832). [23] NBHS Reg No: 21304803. Description: Triple-arch road bridge over river, dated 1831, with U-cutwaters, ashlar abutments, rubble stone parapet walls having stone-on-edge copings, inscribed plaque and ashlar piers to each end of parapets. Swept arched openings with ashlar voussoirs. Weir to downriver side. Plaque inscribed: "O'Connell Bridge built by Robert Bourns Civil Engineer". https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/21304803/oconnell-bridge-gearha-ma-by-kerry On the night of 22 March 1903, heavy rainfall caused damage to O’Connell Bridge, and other bridges in the locality including ‘the near destruction of Currans Bridge and serious injury to the foundations of O’Connell’s Bridge and Marshall’s Bridge [otherwise Maine Bridge at Riverville, Inchinveema]. At Pound Road Lane, Castleisland, the bridge there was partially destroyed and another at Lockfouder was ‘completely carried away’ (Kerry Weekly Reporter, 16 May 1903). Tenders were sought by Singleton Goodwin, County Surveyor for Kerry, in May for the rebuilding of Currans bridge, the repair of O’Connell’s bridge and the repair of Marshall’s bridge, Riverville. [24] Limerick Chronicle, 30 March 1833. The following month, ‘Mr Bourne’s coaches commenced running from Tralee and Killarney to Limerick through Castleisland, Abbeyfeale, Newcastle and Rathkeale on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, then return to Tralee and Killarney on Tuesdays, Thursday and Saturdays, resting in Tralee and Killarney on Sundays. Mr Bianconi’s cars bring the mails daily from Limerick, to Tralee and Killarney’ (Tralee Mercury, 10 April 1833). [25] The following report shows Mr Bourne’s presence in the market in 1829: ‘The road which leads from Dublin to the South of Ireland, by Limerick, is in as good order as a road of its length can be expected to be … the care and supreme direction of the Limerick road is vested in an individual by name Bourne – not the gentleman of that ilk from whom no traveller returns, but a very notable proprietor of mail and stage coaches. Such ‘double trust’ gives him an almost absolute power over the locomotive part of the community and like other autocrats, he is not at all slack in making use of it. His are the only coaches upon the road; for all chance of successful competition must be but of the question so long as he turns the key in the turnpike gates, which very unlike angels’ visits, are as close neighbours as if they belonged to the Wellington Trust. This power then, of taxing a rival, would always give Mr Bourne the whip-hand of his own road. But, not content with so much, he is further authorised to exact twice the amount of the ordinary toll from all carriages plying for hire, by way of a penalty, I suppose, upon the presumption of those who would dream of opposing him. This is his undoubted right by virtue of an Act of Parliament; and, what is worse (he probably would say better) the privilege is secured to him for a quarter of a century to come. It is, in effect, such a monopoly as a King of Spain might graciously bestow upon one of his Grandees; but I hope it is without a parallel in any part of this free country. As for the individual himself, he is a respectable and worthy man, and wholly exempt from blame unless it be a fault to ‘take his fortune.’ The honour and glory of the affair belong to a set of honourable gentleman who were, on all occasions, prodigal-givers-away of the rights and the money of other people – gentlemen who, in their collective capability are dead and damned (as Swift said or might or would have said) 30 years ago. The Limerick Road Act was one of the last, and not the least characteristic jobs of the Irish Parliament, that assembly which the great modern reformer O’Connell wants to evoke its grave of putrid iniquity to shake pestilence and war once more over this ill-fated country. If such an obstruction to free-communication existed in any of the leading thoroughfares of England, even in the north of Ireland what hundreds of petitions we should read of, and how many wise and spirited observations would be made in the House by the Members of every county and borough along the line of roads! But these Munster people are fellows of no real independent feeling. Catholic affairs are for ever running in their heads; and they have neither eloquence nor indignation for anything else. The Limerick road runs through counties which are represented by some of our most talkative and meddling patriots – yet they too, are silent upon the subject. How often has Sir Henry Parnell, how ten times oftner has Spring Rice, bothered the House and the nation about that old wives’ fable, the Treaty of Limerick! But neither they nor their mute and honourable colleagues have ever moved for a copy of the Limerick Turnpike Act. And yet that is a practical grievance which every one of their constituents, Protestant and Catholic, must feel every time he passes between Dublin and the Treaty-stone. This is Irish patriotism of the thoroughbred sort. Anything that will make a xplass and get himself talked about is the labour genuine Liberal delights in; what is merely useful and not ornamental, he despises. The Treaty of Limerick was fertile in fine tropes and constitutional clap-traps. The Turnpike Act is a mere mechanical affair which handled as cleverly as you can will procure you but few and make no figure at all in the newspapers. I wish Mr O’Connell, who is such a dab at driving coaches and six through Acts of Parliament, would try his law breaking first upon this. It materially affects his own constituents, those few of them, I mean, who do not: Trip it, as they go/On the light unshodden toe. But, though I build a great deal of my hopes upon Dan, in this particular, Gurney is likely to prove the better Nomoclast. He will drive a steam coach through these gates long before the Member for Clare turns out his six inland to batter them down. The toll-gatherer can oppose no legal bar against a carriage drawn by smoke; and, if the great Agitator will only keep us in hot water, Gurney will make it run, anything in all the Acts to the contrary notwithstanding. Bless me, what a trite and tedious subject is a turnpike-road, and more especially if it be parcelled out by Irish milestones. When I sat down upon my travels I thought I was in honour bound to say something upon the subject but, if I had thought it would cost half the paper and good apan ink I have expended upon it, it might have lain there to be trodden under foot by man and beast for me. Now, I perceive that Stare super antiquas vias is no such silly motto after all, seeing it is so hard a matter to get along upon them. But unless we take ourselves away from these highways we shall never be able to proceed upon our journey and therefore not one word more – En Route. Besides the Limerick mail and day coaches which are equal in speed and convenience to any vehicles of the same class that I have seen in England there are numerous rickety machines called caravans which cover the ground at the rate of five Irish miles an hour. These are long, narrow, ugly, shapeless, top-heavy, break-neck contrivances, in form and moving similar to the Umnibus, but constructed with a studied attention to the inconvenience and discomfort of the passengers. They were invented expressly for the poorest of his Majesty’s wandering subjects; and if it was the wish of the proprietor to frighten persons of a higher class out of them into his coaches, I don’t think he could have hit upon a happier order of carriage architecture. Nevertheless, a number of decent people put up with the promiscuous society and other annoyances in consideration of the comparatively reduced fares; and the speculative traveller will meet a greater variety of men and manners in an Irish caravan than in any other moving receptacle of the human species at this side of the Atlantic. Indeed it may be said of the horses which pull these machines, as Dr Johnson said of Shakespeare, each change of many-coloured life they draw; for, from the pig-jobber with his clouted brogues, to the fine lady who keeps her inside jaunting-car, and a boy in the livery to guide it, all grades and degrades of society are crammed into the caravan on a footing of perfect equality. It is a carriage for all men (and women too) who can pay; and hence – ni ego fallar – the Gallo-Latin name of Omnibus. Pat Pry’ (Tralee Mercury, 25 November 1829). ‘We perceive with pleasure that the monopoly so long enjoyed by Mr Bourne on the Dublin and Limerick road has been put down by a few public-spirited individuals. A new Coach Company has been just formed which will confer great advantages on the public. The fares are considerably reduced and the carriage of parcels is reduced by one half. We commend the ‘Free Trade Company’ to the public for we are friends to opposition of every description. We hope that the advantages to be derived from cheap travelling will be extended to Kerry. Let us have a branch ere by all means. The public can travel from Dublin to Kilkenny for 6s; and why should we in Munster pay 13s for an equal distance – from Limerick to Tralee’ (Tralee Mercury, 16 June 1830). [26] Kerry Evening Post, 30 September 1837. [27] The Bourne family of Terenure House, notably from Frederick Bourne, who purchased the property in the early nineteenth century, is given in The Bourne(s) Families of Ireland (1970) by Mary A Strange, pp169-178 (includes photograph of Terenure House). [28] ‘Kerry New Mail-Coach Roads,’ Freeman’s Journal, 3 December 1831.