A sash used by the Order of Odd Fellows, a fraternal society, is the latest addition to Castleisland District Heritage.[1]

It is generally accepted that the Order dates to the first half of the eighteenth century though great antiquity is claimed for it.[2] This account of its origins was given at an Odd Fellows dinner in 1841:

The Order of Odd Fellows was first established by the Roman soldiers in the camp during the reign of Nero in the year 55. At that time they were called Fellow Citizens. The name was given by Titus Caesar in the year 79, from the singularity of their notions, and from their knowing each other by night or by day; and for their fidelity to him and their country, he not only gave them the name of Odd Fellows but at the same time as a pledge of friendship, presented them with a dispensation, engraved on a plate of gold, bearing different emblems such as the sun, moon, stars, the lamb, the lion, the dove, and the emblems of mortality. The first account of the order being spread in other countries is in the 5th century, when it was established in the Spanish dominions, and in the 6th century by King Henry in Portugal, and in the 12th century it was established in France, and afterwards by De Neville, in England, attended by five knights from France who formed a Loyal Grand Lodge of Honour in London, which order remained until the 18th century (in the reign of George the Third) when a part of them began to form themselves into a union, and a portion of them remains up to this day. The Lodges which now remain are very numerous throughout the world, and call themselves the Loyal Ancient Odd Fellows, being a portion of the original body. The Manchester Unity is of more recent date, although there is no doubt of its emanating from the above source. Its first introduction into Manchester was about the year 1800 by a few individuals from the Union in London, who formed themselves into a Lodge, and continued in connection with them for some time, when a dispute arose which caused the same body to declare itself independent. They have kept their word – independent they have been since.[3]

Order of Liberators

In the early nineteenth century, the work of the Odd Fellows seems to have influenced Daniel O’Connell.[6] In July 1826, he proposed the formation of the Order of Liberators, described then as ‘an institution which bids fair, in time, to be as respectable, and almost as important, as the Order of Odd Fellows in England.’[7]

The object of the Irish organisation differed to its counterpart in that O’Connell sought to assist not the individual, but the nation:

The Catholics of Ireland form a nation – they should have national resources … the Order should consist of three grades; the first, the Liberators, second, the Knights of the Grand Cross; and third, the Knights Companions. They would endeavour to prevail on Lord Clonclurry to become Grand Master … The object of the society would be to bring individuals of patriotic sentiments together to liberate the country from an aristocratical thraldom; to give to the Forty-shilling Freeholders an opportunity of exercising their judgement in voting for Members of Parliament.[8]

‘

The Order of Liberators was dissolved in 1835.[9]

_____________________

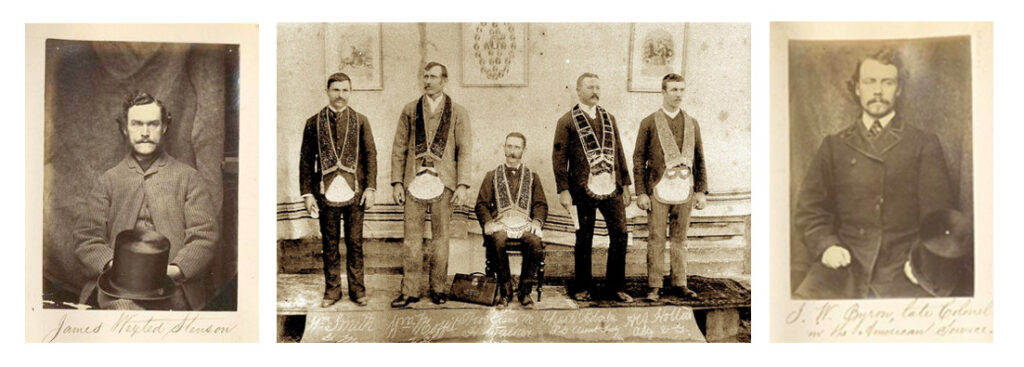

[1] Reference IE CDH 129. The sash was purchased in Walter Lyons, Tralee. An identical sash held in Melbourne Museum https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/items/269624 dates to circa 1949. [2] Odd Fellow organisations were numerous in England, each independent of the others. London Union Odd Fellows, later the Grand Lodge of England, assumed authority over all Odd Fellows there when the Order was revived following suppression in the early nineteenth century. [3] The Wexford Conservative, 3 March 1841. Speech given by Mr Cooper to members from the Greenock district of the Order. ‘They have progressed in number, in talent, in respectability, and now, the flag of Odd Fellowship proudly floats in many a clime – waving on the ruins of poverty and sadness. The Genius of Benevolence may be seen pointing the way where sorrows may be solaced, and poverty ameliorated. Look to the increasing number in Great Britain, the United States, where it has stood the Mast of 20 years and upwards – Holland, Germany, Spain, New South Wales, Gibraltar, Malta, &c, in short, from the burning rays of the torrid, to the cheerless sky of the frigid zone, an Odd Fellow may find a brother who has inspired the same material principles.’ Victory Lodge in Manchester declared itself independent of the Grand Lodge of England in 1809. In 1814, the six Odd Fellows lodges in the Manchester area met and formed The Manchester Unity of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows. Records of the organisation in New South Wales (1854-2004) are held in the State Library of New South Wales https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/YoldElE9. [4] Publican and Colour-Sergeant James Stenson of the Limerick City Militia Artillery was arrested with Sergeant Dunlop under the Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act on 12 February 1866 on suspicion of allowing Colonel Byron, formerly of the United States Army, and others of supposed Fenian proclivities, to enter the Castle Barracks contrary to orders, and ‘to take a view of the interior, paying special minuteness to the battery’ (Dundalk Democrat, 17 February 1866). Dunlop was later released. Stenson was held in Limerick jail and Mountjoy but ‘let out to die’ in May 1866. In September 1866 ‘James William Stenson’ applied for the renewal of his spirit licence; it was opposed by the police on the grounds that he was a ‘suspect’ but ultimately granted. The following year, 1867, he applied for a transfer of licence from Thomondgate to Ellen Street but it was opposed (and refused) on the grounds he had been incarcerated for Fenianism, and also that he had written letters to the press attaching the police for objecting in 1866, which suggested a man of ‘bad character.’ He died on 18 June 1868 at age 34 leaving a wife and four children. ‘After his release from prison, his constitution, which had not been of the strongest, and which suffered much from the incarceration, gradually sank under the weight of an intense anxiety for the comfort and happiness of his family, together with the harsh treatment to which he was subjected while under the more than severe discipline which is practised upon political offenders in the County of Limerick Gaol’ (Limerick Reporter, 19 June 1868). A few months later, his widow received the sum of £7 18s 0d, a second donation from the members of the Loyal Banks of the Shannon Lodge (private subscriptions). In April 1869, his widow Mary applied for a licence to keep the public house in Treaty Terrace, Thomond Gate. It is worth noting here his namesake, James Stenson, one-time reporter on the Sligo Champion, Mayo Examiner, acting editor of the Roscommon Herald, proprietor of the Donegal Vindicator, private secretary to Thomas Sexton MP till suppression of the Land League. This James Stenson was arrested in 1881 under the Coercion Act and conveyed to Galway Prison; he was residing at that time with his family in Sligo (a memoir of ‘J O’C’ published in the Wicklow People on 13 October 1894 stated that James Stinson ‘well known newspaper man’ was transferred with him to Monaghan Jail in February 1882). In September 1882, it was reported that Stenson had obtained ‘a respectable position on the staff of an important journal in the County of Cork’ (Sligo Champion, 2 September 1882). Margaret Theresa, widow of James Stenson, author and journalist, died on 24 June 1932 at Thomas Street, Sligo. The Census of Ireland (1911) records Margaret ‘Stinson’, widow, living with her sister Winifred Scanlan, a shop-keeper, at Thomas Street, Sligo. The photograph of Stenson was taken in Mountjoy Prison by an unidentified photographer in 1866 and is from the album of Sir Thomas Aiskew Larcom, then Under-Secretary for Ireland, held in The New York Public Library https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-9716-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99). The following, which gives background to the albums, is taken from their website (https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/thomas-a-larcom-photographs-collection#/?tab=about&roots=1:927c8ef0-c6bd-012f-1ca3-58d385a7bc34): ‘Laid inside the second volume is a letter from the photographer (whose signature is illegible) to Larcom: "You asked me some months ago to get you the photographs of the convicted and untried political prisoners who have been confined in Mountjoy. // I now send you a most unique 'Book of Beauty' . . . The camera is bad, but I am about to get a better, a really good one." Identified as felons and Fenian political prisoners, the subjects of the photographs in these two albums include some of the leaders of the Fenian Brotherhood and its Irish wing, the Irish Republican Brotherhood. One of these, the early activist Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa (1831-1915), recounted sitting for his portrait: After being shaven I was led to have my picture taken. The photographer had a large black-painted pasteboard prepared, with my name across it in white, and, pinning it across my breast, he sat me in position. I remained sitting and looking according to instructions until he had done, and he never had the manners to tell-what artists never fail to tell me-that I made an exceedingly good picture. [O'Donovan Rossa's prison life: six years in six English prisons (1874) p.73]. In 1859, the City of Limerick Lodge and the Banks of the Shannon Lodge were allowed to leave the Cork District of the organisation to form a District to be called the Limerick District. A special meeting of the members of the Loyal Banks of the Shannon Lodge took place in June 1875 for the purpose of appointing a deputation to attend the O’Connell Centenary. Stephen O’Brien, Mr J J Organ, and four other members were selected by ballot. In 1915, the Banks of the Shannon Lodge met at the Lodge Rooms, 19 O’Connell Street, to offer sympathy to the family of Brother M O’H Lawler, secretary of the Lodge for more than twenty-five years. Two years later (September 1917) the members met at the same venue to record their sorrow at the death of their ‘revered and fearless Bishop, Most Rev Dr O’Dwyer.’ [5] John Whitehead Byron (1835-1909) was born at Clogheen, Co Tipperary in about 1835. He went to America as a child and was one of the first to volunteer under Thomas Francis Meagher in whose Zouave Company he served with the 69th in Virginia in 1861. On the formation of the Irish Brigade in New York, he was commissioned as second Lieutenant of Co E, 88th Regiment, New York Volunteers of which P F Clooney was Captain and W M O’Brien first Lieutenant. He was promoted to first Lieutenant and served on the staff of Major-General Handcock. Subsequently went out with the 88th as Adjutant from which he rose to the rank of Major. Taken prisoner and incarcerated at the battle of Reams’ Station, Virginia in 1864. See biography in Waterford Mirror, 9 May 1866. He was later Commissary Superintendent of the National House for Disabled Soldiers at Dayton, Ohio. He died in 1909 (obituary, Irish Independent, 30 August 1909). The photograph of Byron is held in the digital collections of the New York Public Library (https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-963e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99). [6] In 1822, the Loyal Craven Lodge of the Ancient Order of Odd Fellows in Southampton contributed to a fund for ‘the relief of the distressed Irish.’ Subscriptions amounted to £350 (British Press, 17 June 1822). [7] Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 4 October 1826. Further reference, ‘The Order of Liberators,’ History Ireland, Issue 4, July/August 2020. [8] Dublin Evening Post, 8 July 1826. During a speech given at the Precursor Society, Dublin in 1839, O’Connell alluded to the Odd Fellows as follows: ‘Once upon a time the society of Odd Fellows had a large meeting and a prolonged debate upon the question of appointing a treasurer … one of them stood up and asked if it was not rather a waste of time to debate upon the election of a treasurer when in fact they had no funds. The unlucky member was convicted of common sense and at once kicked out of the society’ (Tralee Mercury, 30 March 1839). [9] The objectives of the Order of Liberators, ‘A Voluntary Association of Irishmen,’ are given in ‘The Order of Liberators’ by Oliver Snoddy, North Munster Antiquarian Journal, No 2 (1967) pp82-84.