‘Rack-rents, insecurity of tenure, ejectment and extermination, these are the master-grievances of unhappy Ireland’ – Rev P O’B Davern

Iconic actor, Robert De Niro, who is currently researching his Irish roots, might well be interested in The Young Irelanders, a rare book recently acquired by Castleisland District Heritage. It was written by the Kerry-educated journalist, Thomas Francis O’Sullivan and published by The Kerryman in 1944. It is a comprehensive record of participants in the Young Ireland movement and underscores the impact of the Nation newspaper and its contributors, male and female, to the cause.[1]

More than one hundred sketches dominate the contents of the book which include the Nation founders Duffy, Davis and Dillon. Among the lesser known appears patriot priest, Rev Patrick O’Brien Davern, who ministered in the parish of Knockavilla, Tipperary from 1839. American-born De Niro, who recently celebrated his 80th birthday, descends on the side of his paternal grandmother, Helen M O’Reilly, from the district of Knockavilla.

Other Irish names that appear in De Niro’s ancestry are Burns, Ryan and Hall.[2] Almost all of these names are found in Rev Davern’s powerful account of landlordism in Tipperary in 1843. His forthright charges against landlord, Viscount Hawarden – which brought about a libel case against the Nation newspaper – help to explain the violent dispersion of people from this district on the eve of the Famine.[3]

In measured, articulate prose, Rev Davern commenced his public assault of Lord Hawarden. The reverend considered his constant interactions with his parishioners – the tenants – and his long residence in the locality rendered him ‘an unexceptional witness in every testimony and deposition charged against Lord Hawarden.’

Writing from Knockavella, the reverend threw down the gauntlet and declared that ‘for the green acres of Dundrum’ he would not become Hawarden’s flatterer or sycophant – ‘the power and grandeur of nobility have no terrors for me.’

He began with ‘Irish husbandry ground down and devoured by rapacious landlords for the last half century’:

The land, which may be considered the raw material, is made productive by the labour, skill and capital of the agriculturist. Its just value can only be appreciated by the current prices of agricultural produce in the market … rent therefore must necessarily vary with the fluctuations of the prices of agricultural produce.

The payment of rent, however, did not guarantee security of tenure:

Never was allegation more justified than that of awarding to your lordship Hawarden the glory or ignominy of ejecting the largest number of tenantry in the county. Over two hundred families comprising 1300 human beings evicted from their cherished holdings on your lordships estate, exterminated root and branch from the land not because they failed to pay the rack-rent but because their tenure was the ‘good or bad will’ of their landlord or his agent.

The people were ‘sent adrift homeless, helpless, pennyless, miserable and destitute … over three thousand green acres of their ancient inhabitants denuded.’ How could Tipperary be tranquil, asked Rev Davern, ‘when the noble of the land will allow thousands of the industrious population, his tenantry, to be driven to starvation and desperation?’[4]

Rev Davern surveyed the history of the Dundrum Estates before they were ‘given by Cromwell to some English adventurer’:

In Irish history the O’Dwyers, the Milesian chieftains and barons of Kilnemanagh, were legally seized with the headship and ownership of that extensive district of this county at the time of Cromwell’s invasion and for many centuries previously … the ivy-clad castles of Killenure, Dundrum and Rossmore are weeping monuments to the ancient glories of the barons of Kilnemanagh.

Rev Davern placed Lord Hawarden in this matrix: ‘You are, my lord, the successor of the Cromwellian settler whose usurpation of the above estates was made legal by the Act of Settlement of landed property in Ireland declared by the Second Charles in the year 1662.’[5]

He continued:

It is twenty years and over since your lordship succeeded your brother, the late Lord Hawarden, in the ample possession of the title and estates belonging to the family … on your lordship’s accession, the family estates, with the exception of the demesne then containing only four hundred acres, were let to tenants at a profitable rent. At present, the Dundrum demesne with the pasturage and tillage land adjoined to it amounts to over two thousand five hundred acres.[6]

This increase of more than two thousand acres was land ‘cleared of its ancient occupants for the purpose of consolidating the same into one extensive farm to be superadded to your lordship’s demesne.’

This ‘clearance’ made way for Protestants:

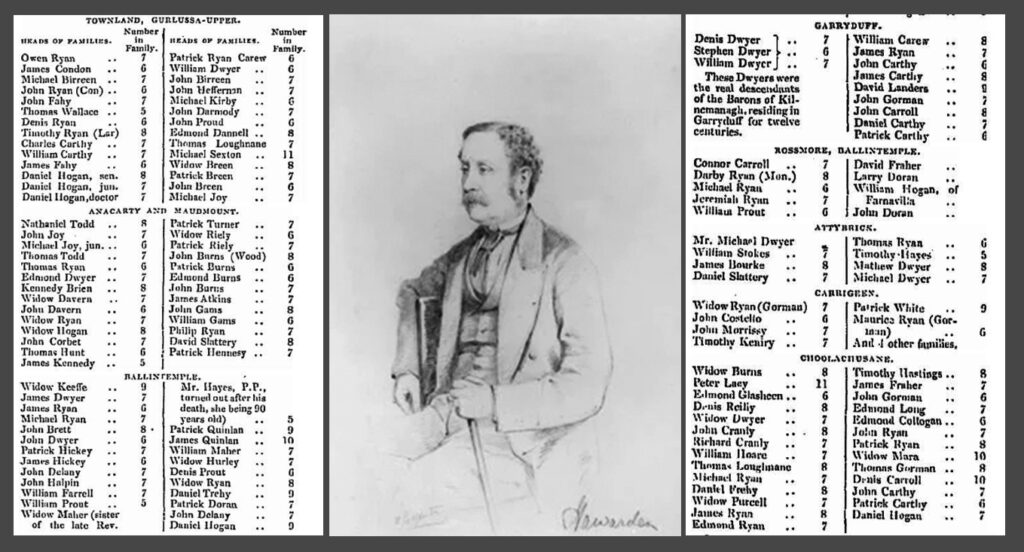

The townland of Carrigeen was denuded of all its Catholic tenants, and they were replaced by two Protestants named Godfrey Taylor and William Lane, the present occupiers. Besides, nearly 300 fertile acres of other townlands, Garryduff, Maudmount, Upper Gurlassa, Attybrick, Anacarty, &c, &c, were stripped of their Catholic inhabitants and let to the present Protestant tenants.[7]

Rev Davern alluded to John Stewart Esq, Lord Hawarden’s land agent responsible for ‘clearances’ whose life had been attempted on three occasions because ‘hundreds had been legally expelled from their cherished tenements, the green fields of their youth’:

Why should your lordship care about the nice sensibility of such feelings when your faithful servant was instrumental in effecting so much good as the wholesale extermination of all the Papist families whose names will be found recorded herewith.[8]

Outcasts on the Highway

Rev Davern asked for sympathy for the ‘afflicted forlorn families’ made victims by agrarian legislation:

Many of them are gone to that bourn from whence no traveller ever returneth. Of the homesteads of their birth, there is not now the smallest vestige to be seen. Their houses were burnt or demolished and they themselves were driven as outcasts on the highway. This expulsion took place in the dearth of summer as well as during the inclemency of winter. Among the evicted were to be found persons of every age and every sex, the widow and her orphan, the aged and infirm, the wife in the throes of labour, the husband in the rage of fever.

Rev Davern described the fate of the displaced:

The bogs and mountains many were obliged to make their resting places – more swarmed into the lanes and alleys of the neighbouring towns of Tipperary, Cashel and Golden, others ventured across the Atlantic when out of season, where some found a watery grave – while the rest prolong a miserable existence among the swamps of North America. Pestilence and fever, generated by famine and starvation, slew their hundreds; but hundreds still survive to eat the bread of sorrow as inmates of the different union poorhouses through the country.[9]

Rev Davern concluded his series of letters with illustrations of rack–renting:

The townlands of Garrane and Kilshinane, the property of Colonel Hyde, of the county Cork, and the townland of Ballinard, the estate of the Marquis of Ormond, all belonging to this parish, and fairly estimated as first and second quality of land, mixed, are let at one pound to twenty-seven shillings per acre. As a further proof of the high rents paid to your lordship, I have made inquiries about the amount of rent paid to Lord Lismore, Mr Scrope, Mr Hunt, and Mr Otway Cave MP whose estates are situated in the same locality immediately adjoining your tenanted property and I find that only seven to fifteen shillings per acres are demanded for land of the same quality for which the tenants of Lord Hawarden must pay thirty to fifty shillings per acre.[10]

He reckoned that ‘one hundred instances’ of similar cases could be given ‘to prove the unmitigated severity with which your lordship’s rents are collected’:

A man named Edmond Ryan, holding a small farm in Coolbane, owed a balance of 1l. 12s. of his rent on last November. Ryan’s turf and potatoes were put under distraint and a keeper was ordered to watch them until payment was made. After fifteen days, this unfortunate tenant succeeded in selling, in the Tipperary market, at a halfpenny a stone, a large quantity of his summer provision and when he offered your subordinate the balance of rent due, he refused taking it, till he should pay the keeper fifteen shillings.

The reverend also cited a case of religious intolerance:

When the present parish priest was appointed some eight years ago he found it necessary to take up a temporary lodging for himself and his curate at the house of a man named Philip Ryan of Dundrum village, who had the kindness to provide them with suitable accommodation. These clerical gentlemen were but a very short time enjoying the comforts of their new lodgings when your lordship, hearing that Popish priests were established so conveniently to your castle, sent for Ryan and ordered him peremptorily to expel his new lodgers or be expelled himself.[11]

Following the publication of his letters, Rev Davern was threatened with prosecution for libel. He was, however, not unaccustomed to or fearful of the consequences of his published statements for he had experienced a similar situation from a correspondence during his curacy at Bruff, Co Limerick. The result of this earlier affair, in which he addressed Daniel O’Connell about the Tithe question, resulted in his transfer to Tipperary in 1839.[12]

Rev Patrick O’Brien Davern

Rev Davern was a native of Ballaghboy, Ballinure, Cashel, Co Tipperary. His sister was a nun in Midleton Presentation Convent, Co Cork, which she served for forty years.[13] His nephew was Rev Patrick R Davern who died from heat exhaustion at Bathurst, Wilcannia, New South Wales, Australia on 17 January 1896.[14]

Rev Davern served Knockavilla and Donaskeigh from 1839 until his death on 30 August 1843, the same year as the publication of his letters:

Mr Davern fell a victim to a malignant fever caught in the discharge of his spiritual duties, and died after an illness of ten days. In the prime of manhood and pride of intellect, he was called from a scene on which he had already shed lasting lustre, by Him from whom he derived his rich inheritance of ability and virtue. Had he been spared, he would have efficiently served his country to which he had given such ample assurance of his fidelity and power.[15]

‘Many and many a tear of honest affection will fall on his green grave,’ wrote an obituarist, ‘for one so gifted on the purity of purpose and singleness of heart.’[16] He was buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s Church, Killenaule. A memorial there is inscribed:

His brief mission was distinguished by many services many virtues rare abilities and earnest piety to sooth the sore of heart to make large the joy of the poor was the great aim of his pious labours if he turned from this sphere for a brief bright time it was but to extend his benevolence to his country to embrace her many sufferings within his comprehension charity & lend to her aid the influence of those high attributes of mind & fervid purpose of heart which that country owned with pride & will remember with affectionate sorrow/His letters on landlordism in Tipperary will live & be cherished they will ever be the proud man’s scurge and the poor man’s protection & the hitherto licensed vice of the great will shrink abashed from their kindling fervours/Death caught in his dutys fulfilment & coming as the sanctifier of his life struck him down young in years but mature in learning patriotism and virtue

Cornwallis Maude, 3rd Viscount Hawarden, died in London on 12 October 1856. He was described in a death notice as ‘a kind and benevolent landlord, who will long be remembered by a grateful and prosperous tenantry.’[17]

__________________________

[1] The Nation founders, Duffy, Davis and Dillon, are dealt with individually in the book of which half provides short sketches of some hundred contributors. An anthology (with contents and alphabetical list of authors) is given on pp425-650 and appendices include a useful list of pseudonyms of Nation writers (pp657-659). An account of journalist and author Thomas Francis O’Sullivan, author of Romantic Hidden Kerry, can be read at this link http://www.odonohoearchive.com/romantic-hidden-kerry/. [2] Helen M O’Reilly (1899-1999) wife of Henry Martin De Niro (1897-1976), parents of Robert De Niro senior (1922-1993) who married Virginia Holton Admiral (1915-2000) in 1942. Their son, actor Robert De Niro, was born in 1943. Helen M O’Reilly was the daughter of Dennis Francis O’Reilly (1866-1952) and Mary F (or E) Burns (1866-1924). Their parents (Dennis was the son of Edmond (Edward) O’Reilly and Ellen Hall and Mary Burns was the daughter of John Burns and Mary Ryan) are believed to have hailed from Tipperary. [3] A series of five letters were published in the Nation between February and April 1843 addressed to Viscount Hawarden, who took the libel case against the newspaper: ‘In the Court of Queen’s Bench on Saturday, the Solicitor-General applied for a criminal information against Charles Gavin Duffey, proprietor of the Nation newspaper, for an alleged libel published in his paper on the 25th of February and 4th of March. The Learned Counsel read passages from the ‘libel’ which appeared in letters of the Rev Mr Davoren [sic] RCC, to Lord Hawarden, under the heading of ‘Landlordism in Tipperary’,’ (Morning Post, 14 June 1843). See Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates: Third Series, 1843, Vol LXIX (1843), p1145. C G Duffy MP gave the following summary of the affair some years later: ‘Mr Davern acquired immense popularity in Ireland in the year 1837 by a series of brilliant letters assailing O’Connell for compromising the Tithe Question. After six years’ silence, he wrote another series in the Nation exposing the enormous extermination of Lord Hawarden in Tipperary. Lord Hawarden was then in the Royal Household and it was understood that he was peremptorily ordered to justify himself or resign. He chose, or made believe to choose, the former course. His solicitor wrote to me that he was instructed to commence a prosecution but that he would proceed directly against the author, if Mr Davern, within a week, acknowledged the letters bearing his signature. O’Connell, influenced, perhaps, by magnanimity, perhaps by that profound policy, which teaches great men how to conquer generous enemies, finding his old, potent, antagonist in this position, immediately wrote to him that the Repeal Association considered this a national contest, and would hold him harmless of expense. Accordingly O’Connell appointed Mr Potter, the late estimable member for Limerick whom at that period, it so happened, I had never seen or heard of – to conduct the case; and vigorous preparations for the defence were begun. The time for substituting Mr Davern as defendant had, however, passed, and my name was retained as nominal defendant. After a little time Mr Davern died; and Lord Hawarden, who had no case and was mortally afraid of exposure, never went to trial. Mr Potter, however, had made the most effective preparations for the defence of a case which O’Connell thought proper to regard as a national one, and had now a heavy bill of costs waiting to be paid. At this time a rumour arose which I could never trace to any certain authority. It was said now that Mr Davern was dead, now that the prosecution was dropt, and no glory to be had of it some of the mean advisers about O’Connell thought it would be a fine stroke of work to throw the responsibility upon me. It would have been a futile attempt, for there was neither moral nor legal claim upon me. I was no more than a spectator of the case; the prosecutor had elected to proceed against the writer; the writer had been guaranteed against expense By O’Connell, the defence was conducted by his own solicitor and at their joint will and pleasure; and I would not have permitted even O’Connell to shift the burthen upon me. But to do him justice, he never exhibited, as far as I know, the smallest inclinations to adopt the dishonest advice of his parasites; after a little delay, he paid the solicitor he had himself employed, and fulfilled the responsibility had had voluntarily embraced’ (Dublin Weekly Nation, 2 December 1854 and Kilkenny Journal, 6 December 1854). Duffy also discussed the affair in his memoir, My Life in Two Hemispheres. [4] ‘Landlordism in Tipperary,’ Letters I and II, Nation, 25 February and 11 March 1843. [5] The Nation, 25 March 1843. Having outlined the history of the land claimed by Viscount Hawarden, Rev Davern alluded to Roman Catholic priest Father Nicholas Sheehy (1728-1766), parish priest of Clogheen, hanged, drawn and quartered on 15 March 1766 in Clonmel jail ‘for the murder of a man who was known to have lived for many years afterwards.’ The man was John Bridge, an informant against the priest. [6] Cornwallis Maude, 3rd Viscount Hawarden (1780-1856), Lord in Waiting 1841-1846. ‘The family of Maude deduces its descent from Eustace de Montealto – styled the Norman Hunter, who came to the assistance of Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, at the time of the Conquest, and having participated in the glory of that great event, obtained, amongst other considerable grants, the Castle, Lordship, and Manor of Hawarden in the county of Flint.’ [7] Rev John Mackey, Parish Priest of Clonoulty and Rossmore, Cashel, addressed a number of open letters to the Earl of Devon in early 1846 about Lord Hawarden’s clearance system and evidence taken from him before the Land Commission which he claimed was published ‘very incorrectly, I am represented in it as having declared, on oath, the truth of palpable falsehoods.’ He takes particular exception to Lord Hawarden’s land agent, John Stewart, and in so doing, goes into detail about local cases. The letters appeared in the Dublin Evening Post in the early months of 1846. In an earlier letter entitled ‘Landlords in Tipperary’ (Dublin Evening Post, 23 December 1843) he had also remarked on Viscount Hawarden’s rack rents. [8] John Stewart Esq was Lord Hawarden’s land agent from 1822 (ref: ‘Samuel Cooper of Killenure (1750-1831) – Tipperary Land Agent and his Diaries’ by Denis G Marnane, Tipperary Historical Journal 1993). He was replaced in 1851 by Richard Uniack Bayly Esq JP of Ballinaclogh, Nenagh. [9] Nation, 25 March 1843. [10] Nation, 22 April 1843. ‘Your unfortunate tenants whom I know to be a sober, peaceable and industrious class of farmers are reduced to such actual poverty and misery that few, if any of them, can allow their little families the small luxury of eating one of the pigs which were fed during the whole long year by the half-naked children at the threshold … hundreds of your lordship’s dependents would have starved during the last five summers had not a few benevolent and charitable persons of respectability in the district purchased for them a sufficient quantity of flour at Mr Mathew’s mill of Golden; and let it be recorded in evidence that this provision was made at a time when hundreds of tons of oatmeal and thousands of barrels of potatoes were stored up at the Dundrum Granary … the superabundance of provisions at present in the country will render the usual oatmeal and potato traffic in next July a complete failure.’ [11] Nation, 22 April 1843. The priests subsequently ‘took up their lodgings in another quarter of the parish.’ In letter 4 (Nation, 8 April 1843), Rev Davern alludes to a ‘late publication’ Dundrum and its Environs, and tackles the politics surrounding Lord Hawarden’s appointment as Lord-in-Waiting on the Queen. [12] Rev Davern’s three public letters to Daniel O’Connell appeared in 1838. In early January 1839, an anonymous writer (‘A Roman Catholic’) addressed a long letter about this affair entitled ‘Summary Justice: Banishment of the Rev Mr Davern’ in which it was alleged, ‘On Sunday the 2d of December Mr Davern received a letter from the Most Rev Dr Slattery withdrawing the jurisdiction of a priest from him, not to be exercised in any parish belonging to his diocese in the county of Limerick, and commanding him to leave Knockany parish [Bruff, Co Limerick] for the parish of Knockavella, Co Tipperary; and, on pain of suspension, to quit Knockany within an hour. No reason was assigned – no cause given – no remonstrance allowed – no inquiry permitted – blind obedience was required.’ [13] ‘With much regret we announce the death of Sister M F Regius Davern, one of the good nuns at the Midleton Presentation Convent who laboured with untiring assiduity and zeal for a period of 40 years as a member of the community. Sister Regius had many relatives who devoted their lives to the service of God and one of them, who was her brother, the Rev Patrick O’Brien Davern, a distinguished priest in the Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly, and also her nephew, Rev P R Davern who died last year in Sydney just at the time when he was about to return to Ireland. The deceased nun entered the Midleton Convent in the year 1853 and died in the 41st year of her religious profession at the age of 81. She was a native of Ballaghboy, parish of Killenaule, Tipperary and was known in the world as Miss M F Davern.’ Funeral report in full in Munster Advertiser, 3 February 1897. [14] A monument to Rev P R Davern of Wilcannia was erected there to his memory by his parishioners. Rev P R Davern was, as far as can be seen, son of James Christopher Davern, the son of Michael Davern and Mary Duggan. [15] Dublin Weekly Nation, 2 September 1843. [16] Ibid. ‘Many a stifled prayer herald his pure spirit on high, and many a blessing will bespeak how beloved his memory while all who knew him live. Gloom will be where his steps have been; but the flock whom he served as a priest, the poor whom he protected, the wronged whom he vindicated, his too bereaved mother, the fond family circle to whom he was an ornament and the faithfullest of friends, who shall supply his place with them?’ ‘Died, of typhus fever, contracted in the discharge of his duty, the Rev Patrick O’Brien Davern, RCC, of Knockavella. This distinguished young clergyman, who yet in early life had shed such lasting lustre round his path, has been suddenly snatched from a scene where, had he been spared, he would have done honour to his profession and substantial service to his country. As an accomplished scholar, a devoted priest, an ardent patriot, and a most faithful friend, society has lost in him an ornament, the country an able advocate, the poor and oppressed an uncompromising defender, and the circle in which he more immediately moved a beloved member. Unnumbered mourners will gather round his green grave to offer there their sincere tribute of unaffected sorrow. The houseless whom he would shelter, the poor whom he would raise up, the beloved flock who loved so well in turn, these will come to mourn to his grave, to tell each other of his faithful services, and to unite in fervent prayer for his eternal happiness’ (Southern Reporter, 5 September 1843). [17] Armagh Guardian, 17 October 1856.