The Geraldines, the Geraldines, ‘tis full a thousand years Since, mid the Tuscan vineyards, bright flashed their battle-spears; When Capet seized the crown of France their iron shields were known, And their sabre-dint struck terror on the banks of the Garonne; Across the downs of Hastings they spurred hard by William’s side, And the grey sands of Palestine with Moslem blood they dyed – But never then, nor thence, till now, have falsehood or disgrace Been seen to soil Fitzgerald’s plume, or mantle in his face.[1]

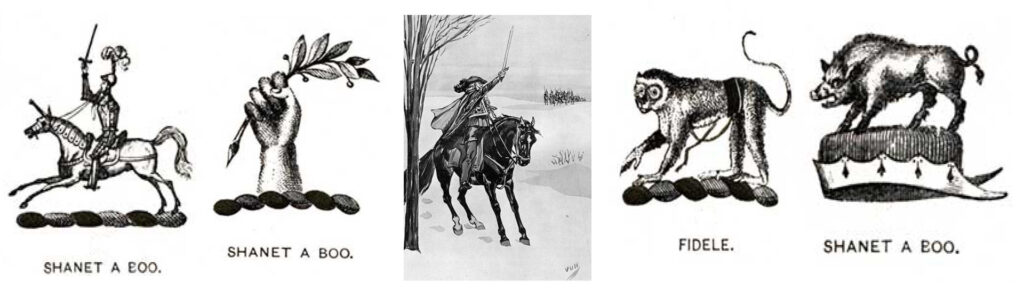

Next year, 2026, Castleisland will celebrate ‘Castleisland 800,’ the octocentenary of the castle from which the town takes its name.

The foundation of the castle is attributed to Geoffrey de Marisco.[2]

There is a tradition that it was by his marriage with Eleanor, daughter of Sir William of Kilmurry, that Desmond got his first lands in Kerry[3]

Just over a century after its foundation, the Castle of the Island was under threat.[4] An entry in the Clyn Chronicles records the war between Sir Ralph de Ufford of Ufford Hall, Suffolk and Maurice, son of the Earl of Desmond, over lands which included Kyrigan (Kerry):

A war between Ralph de Ufford, Justiciary of Ireland, and Maurice son of Thomas, Earl of Desmond; and the justiciar deprived him of his lands, namely, Clomele, Dylsylan, Kysekyl, Oconyl, Kyrigan and Desmonia.[5]

The subsequent Siege of Castleisland of 1345 lasted for about two weeks before the Earl of Desmond’s knights, Sir Eustace le Poer, Baron of Kenlis (Kells) in Ossory (Meath)[6] and Sir William le Grant of Kilmacow were forced to surrender, taken, and hanged.[7] The earl’s seneschal, John Coterel, who served as sheriff of the Liberty of Kerry in 1329-30, was hanged, drawn and quartered.[8]

Ufford, who had been appointed Justiciar of Ireland on 10 February 1344, died from illness on Palm Sunday, 9 April 1346, just months after the siege. The event is recorded in the Dictionary of Irish Biography:

During the summer Desmond went into open rebellion, and Ufford raised an enormous army (by Irish standards) and progressed through Munster collecting indictments against the earl. In October he captured Castle Island, Desmond’s stronghold, had the earl’s leading supporters hanged, drawn, and quartered and his seneschal drawn, hanged, decapitated, his intestines burned, his body quartered, and his limbs sent to various parts of Ireland to serve as a warning for any putative rebels. Fitz Thomas, however, escaped and went into hiding.

Sir Ralph de Ufford also took Yniskysty (Iniskisty), another of the earl’s strongholds, as recorded in the Clyn Chronicles:

Likewise, the castle of the aforesaid earl of Yniskysty, besieged by the justiciar and his men, was stormed and taken on Friday (the feast of Doctor Jerome).[9]

Iniskisty was ‘commonly reputed impregnable.’[10]

The seizure of the castles of Castleisland and Iniskisty, just short years before the devastating plague of 1349,[11] forms part of the colourful era of the Earls of Desmond in Kerry, whose history and character are portrayed in the journal, Earls of Desmond, illustrated by Noel Nash.[12]

The death of Gerald, ‘The Rebel Earl’ in 1583, whose headless body was buried in Kilnananima near Castleisland, signalled the demise of the Desmond era in the county. Edward Walsh offered ‘The Rebel Earl’ poetic rest, ‘at last’:

Now Maing’s lovely border is gloriously won, Now the towers of the island gleam bright in the sun, And now Ceall-an-Anamack’s portals are passed, Where headless the Desmond found refuge at last! By Ard-na-greach mountain, and Avonmore’s head, To the Earl’s proud pavilion the panting deer fled.[13]

In recent times, conservation work has been carried out on what little remains of the once great Castle of the Island. This is timely, for the extensive history of the Earls of Desmond in Castleisland will surely occupy a considerable portion of the anniversary celebrations next year.[14]

Speak low, speak low! The Banshee is crying – Hark to the echo! She’s dying – dying! What shadow flits dark’ning the face o’er the water? ‘Tis the swan of the lake, the Geraldine’s daughter.[15]

____________________________

[1] From ‘The Geraldines’ by Thomas Davis (‘The Celt’), The Nation, 13 January 1844. Jeremiah King, in his History of Kerry (p30) includes a concluding stanza to The Geraldines ‘found among Davis’s papers ... The allusion to the pure, honest W. Smith O’Brien is obvious.’ The following offers background to Davis’s poem: ‘In AD 1337 Maurice, Earl of Desmond, made fourteen knights at Dun Megan, which is called Cell Dumiche in the Book of Armagh. It is believed it was this entry in Clynes Annals that inspired Thomas Davis to write of the Geraldines: Your swords made knights, your banner waved, free was your bugle call, From Shannon’s banks, and Dingle’s tide to famed Youghal. The last line is mine, being more geographically correct than the original’ (Michael O’C Fitzgerald, Bushy Island, Limerick, Irish Press, 26 June 1976. [2] https://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-legacy-of-baron-de-monte-marisco-lord-of-castle-island/ [3] The Lament for John MacWalter Walsh with Notes on the History of the Family of Walsh from 1170 to 1690 (1925) by J C Walsh, p203. [4] https://www.odonohoearchive.com/oilean-chiarraighe-castle-of-the-island-the-album/ [5] The Annals of Ireland by Friar John Clyn of the Convent of Friars Minors, Kilkenny; and Thady Dowling, Chancellor of Leighlin (1849) edited by Very Rev Richard Butler (1794-1862), Dean of Clonmacnois, p31. The Annals of Ireland edited and translated by Bernadette Williams was published in 2007. [6] Following extract from The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory (1905) by William Carrigan: A.D. 1327. (Nov. 29). The town and almost the whole Barony of Kells, in Ossory, were burned by the Lord William de Bermingham and the Geraldines. This petty war between the Geraldines and the Lord Bermingham, on the one side and Arnold le Poer, who had been granted the manor of Kells, after the De Monte Mauriscos, on the other, arose from the offence, taken by Maurice fitz Thomas, the poet-Earl of Desmond, at being contemptuously called a "rhymer," by the said Arnold le Poer. Arnold was soon after excommunicated by Richard de Ledrede, Bishop of Ossory, for his connection with the famous witchcraft-cum-heresy case of Alice Keteller, and, being imprisoned in Dublin Castle, died there, unabsolved from the Church's censures, March 14th, 1329. He was succeeded in the manor of Kells by his son, Eustace le Poer, who, joining in the Earl of Desmond's rebellion, was made prisoner at the siege of Castle Island, in the Co. Kerry, Nov. 21st, 1346 (sic), and two days later was hanged, drawn and quartered for high treason. A.D. 1346. The Barony and Lordship of Kenlis, which belonged to Eustace le Poer, are granted by the King to [Lord] Walter de Bermingham. [7] See The Siege of Castleisland https://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-siege-of-castleisland/ [8] ‘While le Poer and Grant were hanged and drawn, Coterel’s execution went one step further: he was hanged, drawn and quartered. Coterel’s execution was reminiscent of executions suffered in England by the likes of William Wallace and Hugh Despenser the Younger. The evisceration of the body – that is, the removal of the internal organs while the victim is still living – was unusual after about 1330 in England, and yet this is one of the earliest examples to be found in Ireland. Why Coterel was treated more severely than his rebellious companions is unknown. Perhaps Ufford felt that he was closer to Desmond than the other men, and was frustrated that the earl had slipped through his fingers. Or perhaps Coterel was tyrannical. Friar Clyn reports that he was said to have practised many oppressive, foreign and intolerable laws’ (Violence and authority: the sheriff and seneschal in late medieval Ireland by Áine Foley, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy Vol 117C, 185-206, 2017). [9] ‘Meanwhile the justiciary goes through Kerry to O’Conyl, and takes two of the earl’s castles by treachery, to wit, Iniskisty and Castle Island, in which last Eustace Poer, William Graunt and Sir John Cotrell were taken and hanged’ (Annales). [10] Ireland and the Anglo-Norman Church (1889) by Rev G T Stokes, p 311. Iniskisty, otherwise Inniskisty, Iniskysty, Yniskysty, described as near Castle Island, appears to have been Askeaton. See J C Walsh The Lament for John MacWalter Walsh with Notes on the History of the Family of Walsh from 1170 to 1690 (1925). ‘He captured Askeaton Castle, then proceeded to Kerry and laid siege to Castle Island, which offered a determined resistance, but after a fortnight’s siege was forced to surrender’ (The Diocese of Limerick, Ancient and Medieval (1906) by Rev John Begley CC, St Munchin’s, p224). Some sources place the castle in Kerry. J T Gilbert, in his History of the Viceroys of Ireland (1865) writes, ‘The acts of De Valognes, as Justiciary in Ireland, are referred to in the Close, Patent, and Charter Rolls of England. In a letter of 1200, the King mentions him as disabled, from infirmity, to execute his employments in England. The custody of his lands in Ireland was granted, in 1202, to Hugh de Neville, and subsequently to William de Burgh. His Irish property, including the castle of Iniskisty, in Kerry, was, in 1212, restored to his son, Hamon.’ [11] ‘John Clyn’s diary is on pipe rolls … Friar Clyn was a contemporary of Chaucer who at the very same time was writing his Canterbury Tales also on pipe rolls. The terrible plague of 1349: That pestilence deprived of human inhabitants villages and cities, castles and towns, so that there was scarce found a man to live therein; the pestilence was so contagious that whosoever touched the sick or the dead was immediately infected and died; the penitent and the confessor were carried away together to the grave. Through fear and dread men scarcely dared to perform the offices of piety and pity in visiting the sick and in burying the dead. Many died of boils and abscesses and pustules on their shins and under their armpits; others died spitting blood. That year there was a fruitful and abundant harvest beyond measure, but no man to win it anywhere’ (Letter to the Editor of the Meath Chronicle, 11 May 1963, from Beryl F E Moore, MB). [12] Earls of Desmond (2022) produced by Castleisland District Heritage. [13] The writings of Edward Walsh (1805-1850) are collected in A Tragic Troubadour (2005) by John J Ó’Ríordáin CSSR. [14] See the work of Robert McGuire at this link, https://www.castleislandcastle.com/ [15] ‘The Geraldine’s Death Song’ by Isabella Travers Steward from her novel, The Interdict (Vol III, 1840). Isabella Travers, daughter of Robert Travers, was born in Cork in 1796. She married Thomas Fowler Steward of Great Yarmouth in 1827 and her first novel, The Prediction (set in Killarney) was published in 1834. Her literary career encompassed journalism, poetry, and five novels. Mrs Steward died on 22 April 1867.