I say this, the jurymen should not bring me in through the evidence of a child – John Twiss, Speech from the Dock

James Donovan, an emergency-man living in Glenlara, near Newmarket, Co Cork, was bludgeoned to death in the early hours of 21st April 1894. John Twiss of Castleisland and Eugene Keeffe of Glenlara and were charged with the murder and brought to trial in the temporary courthouse in Anglesea Street, Cork on Thursday 6 December 1894.[1]

It was decided that the trial of Eugene Keeffe would proceed first, and Twiss was put back.[2]

Eugene Keeffe was the eldest son of farmer Jeremiah Keeffe of Glenlara. Eugene’s father faced ejectment after having been served with a Caretaker’s Notice on 18 September 1893.[3]

Eugene was a cousin of the Keneally family who occupied the property in which the murder took place. James T Keneally and his family had been evicted from the portion of the house subsequently occupied by James Donovan and they had moved in with his brother, John Keneally, in his division of the same property.[4]

It was and remains uncertain what happened in the immediate aftermath of the murder. Conflicting information failed to provide an accurate timeline. As far as can be seen, the attack on James Donovan occurred at some period after midnight (when a police patrol left Donvan) and about 2am.

The attack was heard by the Keneallys – for it was impossible that it would not have been, living in the same property. However, they chose not to get involved in what they believed was a moonlight raid.

Donovan was discovered by John Keneally at about 5am. He quickly informed his brother, James T Keneally. The Keneallys claimed that Donovan died at about 8am before the arrival of police, doctor and priest. It was also claimed that the dying man was given milk to try to revive him.

Dr Walter Kavanagh Verling’s findings differed to the story of the Keneallys. The doctor attended the victim at 10am and found his skull smashed. He estimated the time of death to have been between 3am and 5am.

He saw the body of James Donovan about ten o’clock on the morning of the murder. From the state of the body he would say that death had occurred between three and five o’clock that morning. He made a post mortem examination and found the left side of the skull fractured. Pieces of bone were driven in on the brain. Rigor mortis was just beginning to set in in the jaws … Death was caused by haemorrhage and concussion of the brain caused by a fracture, the result of direct violence.[5]

The police were summoned though it was far from clear from where or in which order the officers arrived on the scene. Newmarket and Taur barracks were some miles away.

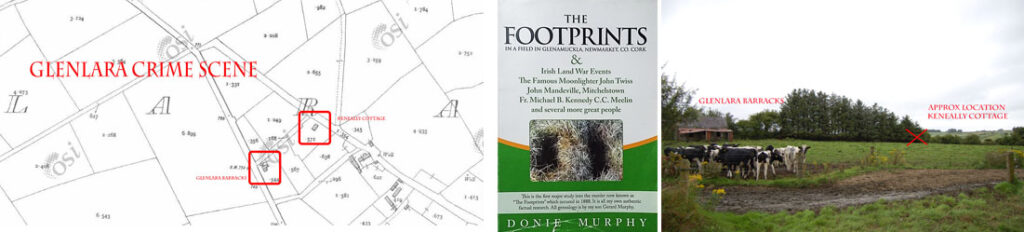

Glenlara barracks, however, was almost on the doorstep of the crime scene. Local history researcher, Donie Murphy, in his book, Footprints, posed the question: Were the police asleep or were they aware Donovan was going to be moonlighted?[6]

It is an important question. If the Glenlara barracks was operational in 1894 (for it has been suggested locally they were disused from 1893) then it stands to reason that the first official on the scene would be from Glenlara, just yards away.

In fact, it appears as if the authorities tried to airbrush Glenlara barracks out of the courtroom. It could be argued that this was to conceal the embarrassment of an horrendous murder committed within earshot of a police barracks or to silence the evidence of the first official on the scene.

‘The police on trial’

Few trials of the 19th century gripped the public imagination with the same intensity as the trial of John Twiss[7]

Eugene Keeffe was successfully defended in court by Cork barristers, Arthur Hackett and Brereton Barry.[8] They were an impressive duo, and certainly impressed Lord Chief Baron Palles, who commended their abilities at the end of the trial:

In the course of my experience extending over twenty-one years, I have heard a great number of important cases and I have never heard a prisoner’s case put forward better or more eloquently.[9]

Indeed, Arthur Hackett was given a ceremonial send-off when he left the country to practise in Perth, Australia in 1895 and Ralph Westropp Brereton Barry would go on to become a judge.[10]

It would be a hard act to follow.

‘The whole fabric of the case rested on the evidence of the young boy Donovan’[11]

At both trials – Twiss was brought up before a Cork jury the following month – much weight was put on the ‘evidence’ of James Donovan’s six or seven-year-old son, John, who witnessed his father’s murder.

This ‘evidence’ however, was tainted from the outset, as recognised by Twiss in his impassioned speech from the dock following his conviction:

I am satisfied to die, for I am not guilty and I am not ashamed of it … And I should think my Lord should take it into consideration, and take the evidence of a child between six and seven years old, and bring him to hang a man wrongfully … he could not identify me at first, and he identified me nine or ten days afterwards … I say this, the jurymen should not bring me in through the evidence of a child … Keeffe was brought in for that murder, and the child swore plump, ‘That is the man that murdered my father’ … The police tried to break down the melt in me … ‘If there is only the evidence of a child of five years old against you,’ says one policeman, ‘a Cork jury won’t have a Kerryman do the like again – .’[12]

Eugene Keeffe’s defence team, however, recognised the shortcomings of ‘evidence’ from so young a child and used the opportunity to rather daringly ‘put the police on trial.’ Without equivocation, Arthur Hackett informed the jury that he was directly charging the police with manufacturing evidence so that they could send Keeffe to the scaffold.[13]

John Keneally took the stand and during examination by Arthur Hackett, stated that Constable Harte had attended the scene of the murder and asked Donovan’s son if he knew the man or men responsible, and the boy had replied that he did not.

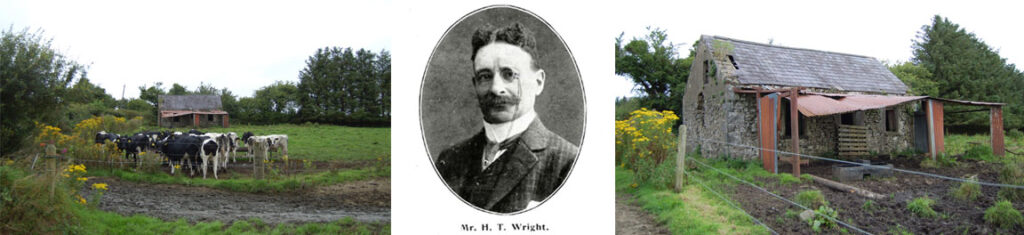

Henry Thomas Wright, Crown Solicitor, in an effort to discredit the statement, stated that there was ‘no such policeman as Constable Harte.’ Wright ordered all the police engaged in the case to be lined up before Keneally, who failed to identify the constable because the constable was not present.[14]

Keneally then named the Glenlara police barracks as the place where Constable Harte was stationed. District Inspector Monson was questioned on this point by the Attorney General (Right Hon Hugh Hyacinth O’Rorke MacDermott, ‘The MacDermott,’ Prince of Coolavin, QC), and conceded there was a policeman named Harte at Glenlara Barracks.

Brereton Barry declared, ‘So much for the value of statement of the Crown Solicitor that there was no such person.’[15]

It was revealed that Constable Harte – a crucial witness if he was first on the scene – had since been stationed in Galway. He was not present at the trial.

Without Constable Harte’s testimony, if indeed he made one, it cannot be known what scene presented when he attended the cottage at Glenlara on the morning of the murder nor the important and possibly first statement of the boy. Nor can Constable Harte’s whereabouts be accounted for when a man was being murdered practically on the doorstep of his barracks.

In Constable Harte’s stead, Constable Cook was examined because he had been in the room with Constable Harte. In reply to Mr J F Moriarty, Sergeant Cook confirmed he knew Constable Harte and that Harte had been stationed at Glenlara at the time of the murder. He further acknowledged that Constable Harte had gone to the scene of the murder before him.

Cook added that he ‘did not believe Constable Harte asked the boy who killed his father’ and reckoned that while Constable Harte and he were in different parts of the house, ‘the boy might have said to the constable that he would know the men.’[16]

To add to this confusion, it was further revealed that young John Donovan had stayed in the house of a sergeant of the police whose wife, Mrs Mahony of Dunbar Street, had been teaching the child the Catechism.

Counsel for Keeffe lost no opportunity in charging the police with manufacturing evidence in the case of the little boy. With the Crown’s case weakened so ably by the defence, the charge against Keeffe would be decided on his whereabouts on the night of the murder.

Keeffe, however, had a strong alibi for his movements, and was thus acquitted and immediately discharged.[17]

Repercussions

John Twiss more than anyone understood the manufacturing of police evidence to ‘solve’ crime because it ultimately put a rope around his neck. It was stated that when Sergeants Murray and Sandles put the hand of the Crown on John Twiss, the police possessed no more evidence against him than they did when they were first called to view the body of Donovan.[18]

It was clear that nobody but the Keneally family could ever truly know what occurred in that cottage during those dark hours of 2 to 8am on 21st April 1894, a cottage generally occupied by, in total, four adults and ten children. But one thing was certain: it was far from pleasant.

The ruined Glenlara barracks still stand and one can only look upon the old stones and wonder what happened there almost 125 years ago. The Keneally cottage has long been pulled down but fallen walls have not silenced the cries of James Donovan: his murder remains unsolved.

It has been said that the blood of John Twiss will forever stain Glenlara, but this need not be the case. The time has come to properly acknowledge the wrongs inflicted on him by a system that allowed it to happen.

The first step is formal apology to the family of John Twiss by means of a Presidential Pardon. It would be a major step in the healing process.

______________________________

[1] The courthouse in Washington Street, Cork, had been partially destroyed by fire on 27 March 1891 and its redevelopment was incomplete. [2] Chief Baron Palles had made it clear he would not fix the trial for any day that would carry it over to a Sunday as he would not keep the jurors locked up on that day. ‘If counsel would tell him that the case would finish at a reasonable hour on Saturday night he would fix it for Friday’ (Cork Constitution, 5 December 1894). The hearing was fixed for Thursday 6 December at 10.30am. The trial of Twiss was carried over to January 1895. [3] Southern Star, 29 November 1930, ‘The Newmarket Murder.’ The notice expired on 18 March 1894, a month before the murder. Jeremiah owed more than seven years rent. An outline of an ejectment obtained against him at Mallow Session in April 1893, and an eviction-made-easy notice converting him into a caretaker, in Irish Examiner, 16 July 1894. Thomas Peters, assistant to Hatton Ronayne O’Kearney (1834-1904) agent of the Earl of Cork, stated in court that ‘since the date of the murder Jeremiah Keeffe had settled with the landlord’ (Irish Examiner, 7 December 1894). [4] James Keneally, son of Daniel Keneally, was cousin of James T Keneally. James Keneally gave evidence at the trial, and stated that his father Daniel’s house was ‘about 100 yards from the house occupied by James T Keneally and Donovan.’ The house was also in the same yard as Eugene Keeffe. Keeffe’s mother and James T Keneally were first cousins. Thomas Michael Keneally, author of Schindler’s Ark (1982) is descended from the Keneallys of Glenlara. One of the author’s forebears, John Keneally of Glenlara, was arrested for Fenian activities in 1865 and subsequently transported: ‘In Cork City the chief organiser all looked up to was John Keneally’ (Cumann Staire (2000), ‘The Ballingeary Moonlighting Case of 1894’ by Manus O’Riordan). [5] Skibbereen Eagle, 19 May 1894 & Cork Constitution, 7 December 1894. [6] ‘The Glenlara Murder,’ The Footprints in a Field in Glenamuckla, Newmarket, Co Cork (2013) by Donie Murphy, p67. Donie calculated the barracks was within 60 metres of the Keneally property. [7] Weekly Examiner and Cork Holly Bough, Christmas issue, 1953, ‘The Dramatic Trial of John Twiss’ by T Higgins. [8] Instructed by solicitor H H Barry, Kanturk. [9] Cork Constitution, 8 December 1894. [10] Arthur Hackett was called to the Bar by Lord Chancellor Ashbourne in 1890 following which he practised at the Assizes and High Courts ‘with considerable success.’ He was entertained to a supper at the Shandon Club and presented with a gold repeater watch, and an address, on his departure to Perth, Australia in 1895, ‘He was now on the recommendation of his friend, Mr M J Horgan, about to leave for Australia to take up the practice of his profession there in conjunction with Mr Horgan’s brother.’ The supper was presided by the Mayor of Cork, P H Meade, and among those present were Brigade Surgeon-Lieutenant-Colonel Hackett, M J Horgan, solicitor and D Keneally (Cork Constitution, 26 August 1895). Ralph Westropp Brereton Barry (1856-1920) eldest son of James Barry, solicitor, Limerick and nephew of Lord Justice Charles Robert Barry. Called to the Irish Bar in 1880, elevated to county court judge for Kildare, Carlow, Wicklow and Wexford in 1902. See Some Members of the Munster Ciricuit (1946) by Patrick Lynch. [11] Irish Examiner, 16 July 1894. [12] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/death-before-dishonour-john-twisss-speech-from-the-dock/ [13] Kerryman, 19 March 1955. [14] Image of Wright in Cork and County Cork in the Twentieth Century by the Rev Richard J Hodges / Contemporary Biographies Edited by W T Pike (1911). [15] Cork Constitution, 8 December 1894. [16] A Constable John E Harte, RIC, is recorded in Galway in the census of 1901 and 1911. Constable Harte appears to have been stationed at Glashakinleen in early 1894: ‘A young constable named Patrick McSwiney who had been stationed at Glashakinleen Protection Post suddenly and mysteriously disappeared under circumstances of a very peculiar nature. On Friday evening last Constable McSwiney in company with Constables Hart and McCaffry from the same station, attended Newmarket Petty Sessions and while on the way home he was missed, and search made at a ford in the river which he should have crossed ... at a bend below the ford the helmet and walking stick of the missing constable were found ... Constable McSwiney hailed from West Cork, Timoleague being his native parish’ (Cork Constitution, 29 January 1894). [17] Cork Constitution, 7 & 8 December 1894. [18] Kerryman, 19 February 1955.