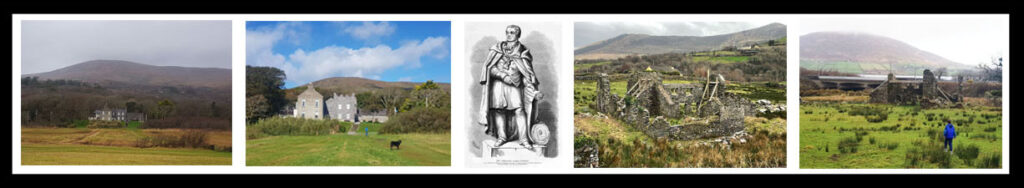

Past West Cove, the road carries one down to the village of Cahirdaniel. Nestling in its woods under the towering hills, and beside a stretch of golden strand where the Atlantic flings its wrecks unchecked, lies the home of O’Connell. Derrynane! Truly a home for a chief[1]

‘There is an old proverb,’ wrote O’Connell in an open letter to the press in the year 1836, ‘which says one fact is worth a ship-load of arguments.’ The ‘one fact’ which formed the subject of his letter related to a situation in Caherdaniel in his home parish.

In a carefully constructed letter, he outlined his concerns:[2]

I have a residence in Ireland – it is in a parish called Kilcrohane, in the county of Kerry. The parish is in length about seventeen miles, the breadth from three to four. The present population is 10,154. Of these there are Catholics, 9,990, Protestants, 164. Of these Protestants there are 87 consisting of coast-guards and police with their families. These persons are not, properly speaking, parishioners. They are employed in the public service, removable at pleasure, and always removed at stated periods; in short, strangers, being in the parish only for a particular purpose and for a limited time. The Protestant parishioners, therefore, are only 77. But reckon them all and the case stands thus:

Catholics 9,990

Protestants 164

Writing from Langham Place (25 June), O’Connell explained that Rev Longfield had been the Protestant rector of the parish for ten or twelve years, ‘I believe he has not been as many days in the parish. I never saw him, and the only service he ever did me was leaving his usual residence at Bath or Cheltenham, and coming to an election to Kerry for the purpose of voting against me –that is all.’[3] O’Connell calculated Rev Longfield’s composition for tithes out of the parish at £550 per annum, or thereabouts:[4]

The case then is this – I, as a Catholic, have to support my own clergymen, to build my own church, and keep it in repair. The parish is poor, and the principal burden of all these falls on me; and now the Rev Mr Longfield insists that in addition I shall pay him £50 a year for tithes; and because I deem this demand, as it manifestly is, most unjust and unreasonable, he causes a bill to be filed against me in the Court of Exchequer, hands me over to a voracious attorney to mulct me in heavy costs, and then, forsooth, tells me that the religion which stimulates him to and sanctions this gross and palpable injustice is better than my religion.

O’Connell vowed he would not pay ‘one farthing’ to the Protestant church:

I do not believe it, Englishmen, I do not believe it! I think my religion is better than his; and, therefore, I never will pay him one shilling – no, not one farthing. He and his attorney may seize my cattle, my corn, my furniture – they may distrain my tenants – they may sell, carry away, or destroy – I never will pay one penny.[5]

In conclusion O’Connell pronounced: ‘This is my statement of fact.’

A little over seventy years after the death of Daniel O’Connell, and more than a decade after the opening, in 1902, of the O’Connell Memorial Church in Cahersiveen, a Protestant Church was erected in Derrynane.

It was short-lived. Indeed, there is almost no memory of it in the neighbourhood, though a field known as ‘the church field’ may offer a clue to its transient existence.[7]

Save Derrynane Fund

In July 1946, as the nation approached the centenary of the death of O’Connell, a meeting was held in Clery’s Restaurant, Dublin to discuss the future of Derrynane House. ‘Many heads would hang for shame if Derrynane were purchased for a holiday camp or tourist hotel,’ said Mr Dillon, TD.

Denis Guiney, Brosna businessman and owner of Clery’s, subsequently chaired a meeting of the Save Derrynane Committee to have the house preserved as a national monument. He initiated the campaign with a subscription of one thousand guineas.

It was announced at a later meeting of the committee that the O’Connell family were not selling Derrynane but presenting it to the nation. Denis Guiney announced that the Save Derrynane Fund would be administered by a trust and used for restoring and preserving the property.

In 1953, the Derrynane Trust, of which Denis Guiney was President, made a fresh appeal for funds in order to bring the work of the Save Derrynane project to a successful conclusion. The number of tourists visiting the house during the years 1951-1952 had increased by 1000 to 3,100.[8]

In 2021, the figure was 355,000.

____________________

[1] From ‘The Fjords of Kerry’ Freeman’s Journal, 18 August 1894. Extract in full: ‘Past Barranatra, past West Cove, where every nook invites the traveller to leave his coach for a rest upon the waves of the Atlantic that break upon the strand, the road carries one down to the village of Cahirdaniel, which hangs amid hedges of fuchsia on a slope that looks across a broad reach of strand to Wild Darrynane. Nestling in its woods under the towering hills, and beside a stretch of golden strand where the Atlantic flings its wrecks unchecked, its waves unbroken save by the rocky Island of Scariff at the mouth of the bay, lies the home of O’Connell. Derrynane! Denis Florence MacCarthy has sung its beauty, and has not exaggerated. There was a kingly presence there when MacCarthy reached it; he would be a dull Irishman who did not feel the spirit there still. Truly a home for a chief. Inspiration and elevation in its mountains, rest on its yellow beach, the thrill of liberty everywhere. The courteous descendant of the Liberator shows the visitor through the old, irregularly built house. The dining room, where O’Connell dispensed hospitality like a prince; the library, with his books and relics – one that deadly looking pistol; D’Esterre was the cleventh (sic) [antagonist] – the drawing room, with the table and chair which he received when Lord Mayor of Dublin; the little chapel, built as a thanksgiving after his release from prison –a place for an Irishman’s pilgrimage.’ In 1894, the Great Southern and Western Railway Company issued a descriptive brochure, The Lakes and Fjords of Kerry, to promote new tourist routes. A noted descriptive writer of this period was Professor Grenville Arthur James Cole FGS (1859-1924). [2] ‘Letter to the People of Great Britain’ dated 25 June 1836 published in the Morning Chronicle, 27 June 1836. O’Connell had given an earlier description of his Kerry parish at the Anti-Tory Association; see Reading Mercury, 22 December 1834. [3] Rev Mountiford Longfield (1769-1850). Rector of Desert Serges, Co Cork. Duties in his Kerry parish performed by resident curates. Reference: The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry (2018). [4] O’Connell added, ‘He has also three or four glebes. There are two parishes according to the Catholic division. We, the Catholics, cheerfully support the Catholic clergymen of both.’ [5] O’Connell continued: ‘I will not resist the law, because, like to many other monstrous iniquities, there is law for this also; but I repeat, I never will pay him one shilling – to him, or to his use, not one farthing. Come what may, I never will pay him one single farthing.’ [6] Thomas Henry Nicholson died on 8 March 1870 and tributes identified him as the genius behind the D’Orsay sculptures. ‘Mr Thomas Henry Nicholson, an artist whose works have long been far better known than his name, died on Tuesday, the 8th instant, at his residence at Portland. Mr Nicholson was in early life a pupil of Chantrey, and afterwards of Behnes, from whose studio he was engaged by Count D’Orsay to model a series of statuettes of which the Count assumed to himself the entire merit. After the break-up of Gore House, and the departure thence of D’Orsay and Lady Blessington, Nicholson devoted his talents to drawing upon the wood, and thousands of illustrations to popular periodicals have been the product of his facile pencil. He was of a singularly retiring disposition, and was personally known to few beyond a limited circle of intimate acquaintances by whom his talents and keen original humour were held in high regard. On the accession of the present Emperor of the French – who well knew the secret of the so-called ‘D’Orsay sculptures’ – his Majesty wrote to Nicholson offering him a high position in connection with the fine arts at Paris. Mr Nicholson’s forte lay in the drawing and modelling of horses and figures in motion. His most rapid sketches exhibited a vitality and action which peculiarly distinguished his works from the studies by more laborious artists of draped lay figures, studies from ‘placed’ models, and carefully-posed groups drawn from the life’ (The Graphic, 12 March 1870). ‘Mr Thomas Henry Nicholson, artist, died at Portland, Dorset, on Tuesday aged about fifty-six years. At the outset of his artistic career, Mr Nicholson devoted himself to sculpture, in which line he attained to very considerable excellence, the delineation of horses being his special forte. It is generally understood that the D’Orsey sculptures, for which the Count obtained so much credit, were mainly, if not entirely, the work of Mr Nicholson. In later years the deceased gentleman gave much attention to drawing and engraving on wood, and contributed to the pages of the Illustrated Times, the Illustrated London News, and other periodicals. I can hardly say that Mr Nicholson was well known, for his modest, retiring disposition made him shun general society; but he was warmly esteemed by the few friends whom he admitted to intimacy, and his works were admired by many to whom his person, and even his name, were unknown’ (Illustrated Times, 12 March 1870). Nicholson’s sister, Mary Ann Nicholson, was married to sculptor Neville Northey Burnard (1818-1878) in London in 1844. In March 1870, the youngest of their four children died from Scarlet Fever and was buried with her uncle in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Broadwey, Dorset. The following from British Listed Buildings: ‘Headstone. 1870, to Thomas Henry Nicholson, and Charlotte Neville Burnard. Portland stone. An unusual 'portrait' memorial, a lofty slab with rounded head, with carved drapes over a sunk panel with the heads of the two deceased in profile, and an artist's palette between in low relief. The inscription records Nicholson as an artist, who lived from 1815 to 1870, and Charlotte (1858-1870) the youngest child of his sister Mary Ann Burnard and her husband, sculptor Neville Northey Burnard, who was also responsible for carving the monument. Listing NGR: SY6677383530.’ Thomas Henry Nicholson, son of Thomas and Sarah Nicholson, was born on 13 February 1815. He was baptised in the county of Middlesex. His sister, Mary Ann Nicholson, was born 16 October 1819 and baptised in St Saviour’s, Southwark, Surrey, in 1820. Her father was described as a grocer, address Union Street. He was deceased at the time of her marriage in 1844. Their mother’s name may have been Sarah Pike. [7] http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-iron-church-darrynane-and-the-earls-of-dunraven/ [8] IE CDH 99. News article (Kerry’s Eye, 26 January 2023) relating to an exhibition about the history of Clery’s held in-store in the O’Connell Street, Dublin establishment. Article contributed by Gina McElligott, Castleisland, former editor of In and About Castleisland together with a number of photographs from the exhibition taken by Gina. Denis Guiney (1893-1967) and his wife Mary Leahy (1901-2004) were owners of Clery’s from about 1940. Denis, son of Cornelius Guiney and Julia Crowley, was born at Knockawinna, Brosna, Co Kerry on 9 September 1893. He worked in drapery stores in Killorglin and Killarney before going to work in Dublin. He opened Guiney’s Store in Talbot Street, Dublin in 1921 but it was destroyed during the Civil War. He married Nora Gilmore of Lakeview, Moylough, Co Galway on 13 June 1921; she died at her home, ‘Auburn’ 118 Howth Road, Dublin on 10 March 1938 aged 38. He married secondly Mary Leahy, Creeves, Askeaton, Co Limerick on 19 October 1938. Two years later he purchased Clery’s and transformed it into a multi-million pound enterprise. Denis Guiney had no children from either marriage, and died in the Mater Private Nursing Home, Dublin on 7 October 1967. Chief mourners at his funeral included his brothers, John Guiney, Corbetstown House, Killucan, Co Westmeath; Timothy Guiney, Carrigeen Castle, Croom, Co Limerick; Cornelius Guiney, Rathkeale, Co Limerick and his sisters, Nora Collins, Carrigeen, Croom, Co Limerick and Sheila Fahey, Cremore House, Cremore Park, Glasnevin, Dublin. Mary Guiney died on 23 August 2004 and was buried with her husband and his first wife in Glasnevin. Further reference, Dictionary of Irish Biography, ‘Guiney, Denis’ by Peter Costello.