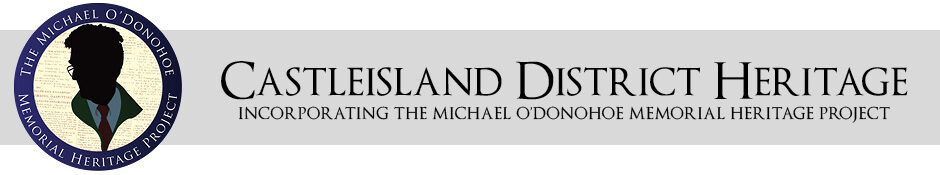

Darrynane Abbey, the Seat of Daniel O’Connell Esq MP in the county Kerry is becoming a favourite subject with the lovers of fine arts in Ireland[1]

This year (2025) marks the sestercentennial of the birth of Daniel O’Connell, ‘The Liberator of Ireland.’ It will be celebrated widely, no more so than at Derrynane House, the former seat of the great man, which is now a museum and visitor attraction.

You true sons of Hibernia, come listen awhile to my song, And when you will hear it, you won’t say it’s wrong. It is of a bold eagle, his age it was over three score, He was the beauty of the tribe, and the flower of Erin’s green shore. From the green hills of Kerry, so merry the eagle took wing, With talents so rare, and in chase he began for to sing. The people admired and delighted at his charming air, And soon they elected him as a member for Clare. Old Ballad

The Catholic Association was described as O’Connell’s ‘Masterpiece’:

Its glorious career for six years, its influence in uniting the millions; its system of protection to the oppressed; of discussion in all forms; its small cost; and its success in 1829 are familiar to every mind … He is the man that has kept the people together.[2]

A masterpiece of a different kind was brought under the public gaze in 1833 with an engraved picture of Derrynane by John Fogarty, who explained it in detail:

The Citizens of Dublin and the Public in general are respectfully informed that a large and beautifully engraved Picture, in perspective, of Darrynane Abbey and its surrounding Scenery &c &c, the Ruins of the old Abbey on Abbey-Island, in the Atlantic – the Mansion-House of Darrynane – the stupendous Mountains and Pleasure Grounds, together with the Rural Irish Sports such as hunting, fishing, fowling, hurling, dancing &c &c, an excellent Likeness of Mr O’Connell, pointing to sports so much admired by the ancient Irish and his certificate of the correctness of the Picture attached to each copy – the Picture takes in a view of at least ten miles square, and there is a printed index attached to each copy – is for Sale on very moderate terms by the Author, John Fogarty, 54 South Great George’s street, from Eleven until Two o’Clock each day (Sundays excepted).[3]

John Fogarty outlined the process involved in getting the image to print:

The Picture of Darrynane has cost a large sum of money, exclusive of nearly three months’ residence in London, absence from home and neglect of business, in order to have it finished in that sytle worthy of the approbration and patronage of the illustrious Patriot whose certificate it bears, and also to meet the approbation and encouragement of my fellow-citizens. I think I hear you say, why not employ an Irish artist that would do the work for half the sum? My answer is there is not an artist in Ireland that knows how to engrave such a landscape picture – no copper-plate press large enough to print it, not even a sheet of paper fit for such a picture. Alas, there is no resident Parliament, no Dukes, no resident Lords of the soil, no Noblemen or Gentlemen to protect or encourage the Fine Arts or Artist.[4]

O’Connell attracted the literary arts. In the summer of 1833, Rev William Bilton, author of The Angler in Ireland, unexpectedly encountered Daniel O’Connell at Derrynane:

I rode up to Derrinane House. It is an extensive pile, a most singular jumble of incongruous additions, part of it weather-slated, part of it aping the castellated style. I believe, though, that its accommodation within is much superior to its appearance without. There is some attempt at gardens and grounds immediately around it but neither nature nor western breezes have favoured the Liberator’s improvements. In front is a boggy meadow; and beyond that a ridge of sand, which extends to the shore of the little bay. The situation is wild and secluded, and therefore, strikingly in contrast with the busy scenes in which Mr O’Connell is usually occupied. I rode round the house as near as I could without intruding, and while thus engaged was much surprised to see ‘the Great O’ coming out to meet me.[5]

‘I must do him the justice,’ remarked the Protestant reverend in his book, ‘to say that he accosted me with the politeness of a gentleman, and the hospitality of an Irishman; inviting me, in the kindest manner, as a stranger, to dine and sleep at his house’:

This invitation, however, I was reluctantly compelled to decline, partly from feeling my time to be very limited; but chiefly from the arrangements I had made respecting my car and baggage, which were waiting for me at Sneem. He repeated the invitation more than once, in a manner that both shewed he wished me to accept it, and also that he was not accustomed to be refused: but I obstinately withstood all his solicitations, much to my after regret and thus lost an opportunity of seeing one of the most remarkable men of his time, under peculiarly favourable circumstances. I however gladly accepted his offer of refreshments, and accompanied him into the house.

Rev Bilton provided a descriptive account of the interior of Derrynane House and its décor:

The drawing room into which I was shown, is a new and spacious apartment: the furniture was neat, but nothing more. There were on the walls a few moderate engravings; some that appeared to be Austrian; one of General Devereux; another of Hely Hutchinson; another of the Princess Charlotte. But the two to which he chiefly directed my attention were a pair of engravings representing the principal founders of the Catholic Association; in the centre of the one stands himself; in the centre of the other his only rival at these famous meetings, Richard Lalor Sheil. This led to conversation about the different characters of each individual there portrayed, the portraits of himself, &c; in the course of which he referred with much self complacency to the part he had played on the world’s great stage; but more as a matter of history than politics; it being his prudent maxim to exclude politics from his house, except when all are known to entertain the same opinions. His conversation was replete with anecdotes, chiefly legal; and was very lively, good humoured, and pleasant.

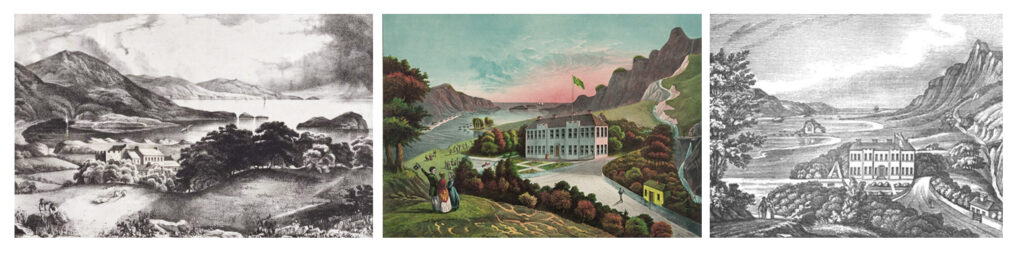

In 1835, William Tait published a book about O’Connell’s life from which the following biography is taken:

Daniel O’Connell is the head of one of those great Irish septs, whose fabulous origin in carried through a vast procession of shadowy kings to the days of the great Milesius … He was born in 1775 near Cahirsiveen in the county of Kerry where the house in which the event took place is still shewn to travellers … His father was Morgan O’Connell of Carhen, in the barony of Iveragh, in Kerry, who was married to Catherine, daughter of John O’Mullane of White-church in the county of Cork. The parents of O’Connell had twenty-two children, of whom upwards of one half lived to beyond the age of eighty. Mr O’Connell was educated on the Continent, partly at Louvain, partly at St Omers, and partly at Douay … he studied his profession in England and was duly admitted to the Irish Bar in Easter Term 1796 … Mr O’Connell married, on the 3rd of June 1802, his cousin Mary, daughter of Edward O’Connell MD of Tralee. He succeeded his father in 1809 and, in 1825, by the death of his uncle, succeeded to the family estate at Derrynane.[6]

I will sing you a ditty, will cause you to smile, Concerning O’Connell and Erin’s green isle, Daniel O’Connell and Erin’s green isle. He says for my dear native country I’ll stand As long as I live, and my name it is Dan, I was bred in sweet Kerry, and trained to the law, Freedom and liberty, Erin go braugh; Here’s Daniel O’Connell, and Erin’s green isle. Old Ballad

In the days of O’Connell, his name was on everyone’s lips in word and song. The poets sang out, for his name equated with hope:

When O’Connell’s voice of power, Day by day, and hour by hour, Raining down its iron shower, Laid oppression low. Denis Florence MacCarthy (1817-1882)

One writer noted that the O’Connell family were ‘proverbial for living to a very old age’:

General Count O’Connell Knt of the Cross of the Order of the Holy Ghost, and Colonel of the late 6th Regt of the Irish Brigade, in the British service, was uncle to the Liberator, he died on the 9th of July 1833 at Muedon near Blois in France, he was the youngest of twenty-two children by one marriage, of whom over one half lived to the age of 99, at which age this venerable patriot died. He was born in August 1734 at Derrinane, the residence of his father, Daniel O’Connell Esq.[7]

Unfortunately longevity would not be the case for Ireland’s Emancipator.

To your bark, brave boys, haste! In our haven’s deep strait is a sail! On through the shallows, and o’er the watery waste For France, with my blessing on the Gale! Maur-Ni-Dhuiv O’Connell[8]

On Monday 6 October 1845, the inhabitants of Castleisland extended a mighty welcome as the Liberator passed through the town en route to a ‘monster meeting’ at the Racecourse in Killarney:[9]

The Liberator entered the kingdom of Kerry. Scarcely had the carriage passed the boundaries when the Liberator received repeated and emphatic marks of esteem and reverence from the people of his native country. Those demonstrations were joined in by the population without a single exception, the aged man, with his foot on the threshold of the grave, raised his feeble voice to pour blessings on O’Connell, and cheer him in his struggle for Old Ireland. The young and the middle-aged cheered him as he passed, and even the children just emerging from infancy clapped their little hands in welcome … When the Liberator entered the town of Castleisland every voice was raised to cry, ‘God bless him’ … never was his name coupled with more glowing eulogium than in this little town of Castleisland [10]

It would be the Liberator’s last triumphant passage through Castleisland.

Honouring a Kerryman born for Greatness

The fierce and restless spirit is all but quenched. The potent demagogue has shrunk into the shuffling invalid

In late April 1847, it was clear to onlookers that O’Connell’s days were numbered. He was in France, where he was observed leaving a hotel supported by his son. As his death rapidly approached, a news reporter predicted that the character of Daniel O’Connell would be an everlasting bone of contention to future historians: ‘Thousands will say, Behold the greatest of patriots, and thousands will say, Behold the greatest of knaves.’

So it has proved with the recent suggestion by Castleisland District Heritage to rename its Main Street ‘O’Connell Street’ for the sestercentennial. The response was rapid: Oh yes he’s The Liberator cries one, He was no freedom fighter cries another.[11]

O’Connell Street or no, the Liberator’s birth is a matter of national celebration this August 2025. Castleisland District Heritage plans to publish a commemorative account of the ailing politician’s harrowing last months when he was taken across the continent, his health subjected to treatments by English, French and Italian physicians whose practice it was to apply leeches, perform enemas, or let blood for ‘congestion of the brain.’

O’Connell’s frail and pitiful state coincided with the famine. As life drained from him, his powerlessness in the face of national calamity greatly affected him. He looked to parliament for fifty million Sterling ‘to be got at any sacrifice’ and urged the gentry of Ireland to rally together if hundreds of thousands of lives were to be saved.

In February 1847, the same month that a rumour went out that O’Connell was dead, the greatly troubled man recognised that England would not go far enough in aid, and rightfully predicted that it would not be until after the death of millions that ‘regret will arise that more was not done to save a sinking nation.’

In O’Connell’s last weeks, determined efforts were made to keep the news of Ireland from him to limit his pained and depressed state.

Had he enough life left to him, the outcome of the famine may have been very different.

________________________________

[1] London Courier, 6 December 1833. [2] The News and Sunday Herald, 24 October 1836. In Kerry in 1829, Richard Meredith of Dicksgrove Esq presided at a conciliation dinner in Castle Island ‘attended by clergymen of both persuasions’ (Chutes Western Herald, Monday 27 April 1829). [3] Dublin Morning Register, 7 December 1833. ‘Daniel O’Connell Esq MP Darrynane Abbey and its Surrounding Scenery The Residence of Mr O’Connell, County Kerry.’ An inscription on one of the prints held in the National Gallery of Ireland gives background: ‘The above picture of my residence Darrynane Abbey and its Surrounding Scenery is a fac simile of the original in my possession drawn by Mr John Fogarty whilst at Darrynane and presented by him to me on my return to London in the year 1831 [signed] Daniel O’Connell’. Reference national Gallery of Ireland: JOHN FOGARTY pinx.t / As the Act directs, July 26 1833/ Published for John Fogarty by Robert Havell, Engraver, No. 77 Oxford Street, London / DARRYNANE ABBEY The Residence of Daniel O'Connell Esq.r M.P. [4] Dublin Morning Register, 7 December 1833. There was an issue with piracy on another view of Darrynane Abbey in the same year: ‘We are authorised by Mr Thomas James Mulvany RHA to state that a spurious copy of his lithographic view of Darrynane Abbey from an authenticated sketch by Christopher Fitzsimon Esq MP has been exhibited for sale in Dublin. Mr Mulvany deems it due to his interest and character to state that he has no connexion with any view of Darrynane Abbey but that which bears his name and that of Mr Fitzsimon’ (The Pilot, 13 February 1833). See the National Library of Ireland https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000547916 [5] Kilkenny Moderator, 22 October 1834. Extracted from The Angler in Ireland or An Englishman’s Ramble through Connaught and Munster during the Summer of 1833 (1834) by Rev William Bilton (1798-1883) MA FGS, Incumbent of Lamorbey, Kent. [6] The Pilot, 9 November 1835. From Ireland and O’Connell: A Historical Sketch of the Condition of the Irish people, Before the Commencement of Mr O’Connell’s Public Career; A History of the Catholic Association; and Memoirs of Mr O’Connell (1835) by William Tait. ‘No vestige now remains of the house in which Daniel O’Connell was born, but Carhan House was built out of the stones of that old house ... No attempt was ever made to preserve Carhan House, it was dilapidated and abandoned even in the Liberator’s lifetime. When I explored the roofless shell, cattle were huddled in it as if weary of the coarse grasses in the marshy field around the ruin’ (‘O’Connell’s House,’ by Alice Curtayne, Dublin Leader, 17 May 1947). ‘Carhan House, the Liberator’s family mansion, there both his parents died towards the end of the second decade of the present [19th] century; but it became uninhabited and dismantled some forty years ago, and now its ivy-clad walls only remain’ (Dublin Weekly Nation, 22 January 1887). [7] Limerick Reporter, 15 August 1843. [8] Maur-Ni-Dhuiv, grandmother of the Liberator. Further reference to Maur-Ni-Dhuiv in The Last Colonel of the Irish Brigade Count O’Connell (1892) by Mrs Morgan John O’Connell. [9] O’Connell was accompanied by William Smith O’Brien, John Primrose and J H Dunne Esq. He had been released from Richmond Prison the year before. His subsequent poor health was frequently attributed to this incarceration: ‘Many attempts have been made to put his deteriorating health down to his conviction and imprisonment but I am not one of them. First of all I heard him complain of the head pains long before he was imprisoned. I can tell you too that his spell in gaol did not impose any real hardship upon him. The Richmond Penitentiary in Dublin had dank and squalid cells to be sure but these were reserved for prisoners who had no influence in the outside world’ (Duggan’s Destiny (1998) by Séamus Martin, p45). [10] Freeman’s Journal, 7 October 1845. [11] In the absence of a body prepared to take up the gauntlet in this respect, it is a case of ‘go on quietly.’