The Beacon Towers Rev Gayer had nearly finished are, as it were, his own tombstones[1]

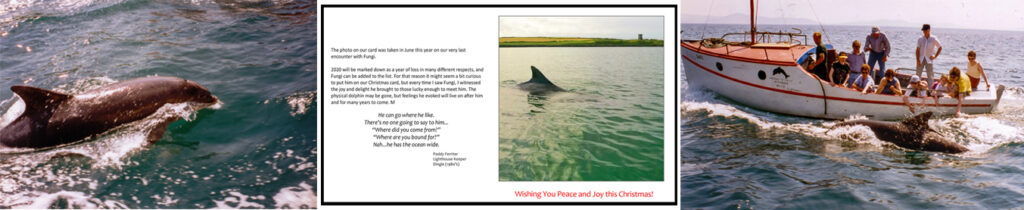

Long before Fungi the dolphin put Dingle Harbour on the map in the 1980s, this particular stretch of water was more renowned for its treacherous conditions and shipwrecks.

Newspapers of the time carried reports of disasters and near-disasters as ships were blown off course by the weather into Dingle Bay. A brief survey of same illustrates the point.

On 17 January 1773, the brig Industry from Philadelphia with a cargo of flax seed, timber and apples was wrecked in Dingle Bay, the captain and cook drowned. Some years later, an unidentified sloop was wrecked on a rock near Dingle harbour and all crew perished. Some empty caskets were discovered the next morning marked ‘Butter, Cork.’[3] In early December 1828, the Belfast brig Veronica was wrecked outside Inch Bar in Dingle Bay.[4] The brig Alarm, laden with coal, put into Dingle harbour having had a very narrow escape of being totally wrecked on Inch Bar ‘with probably the loss of the lives of all on board’ in 1840.[5] The dinghy of HM steamer Pluto capsized near the coastguard station on 7 April 1845 and the corporal of marines was drowned.[6] In October of the same year, the Princess Royal almost perished at Inch Bar but succeeded in getting into Dingle harbour.

It was not just to ocean-going vessels that dangers presented. On Monday 9th April 1838, a young woman named Mary Foley residing at Ballymacadoyle on the south side of Dingle harbour went down the ‘tremendous cliff on the iron bound coast’ to collect shells, as was the custom of the ‘hardy females on that part of the coast.’ A rapid incoming tide left her clinging to a rock for four hours before she was rescued by local man Michael Ferriter, ‘lately a police constable in the district of Kanturk, county Cork.’[7]

The Ballast Board

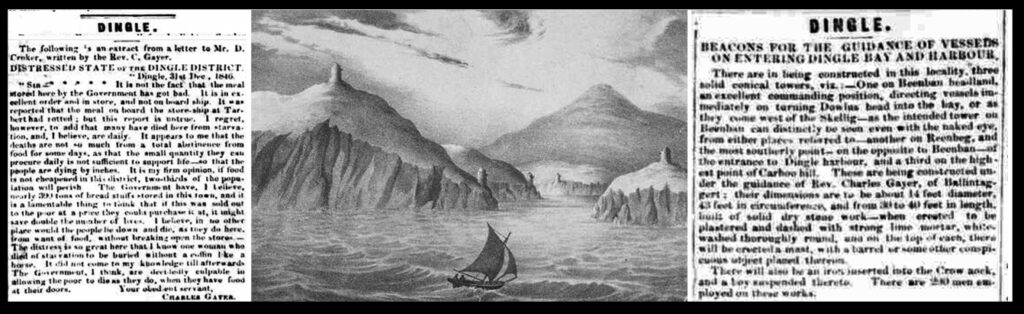

In the early 1840s, the people of the district appealed to the Ballast Board about the need for a small lighthouse at the point of the harbour.[8] It was not until February 1846, at a meeting of magistrates and taxpayers in Dingle courthouse, that approval was given for public works which included a lighthouse at the mouth of Dingle Harbour in the sum of £2,000.[9]

In the meantime, the hazards remained. On 30 December 1846, a vessel laden with about seventy tons of bread stuffs for the Killorglin relief committee went on Inch Bar during a thick fog but was rescued by the coast guards of Lack station. Two-thirds of the provisions were injured.

By the following September, it was reported that ‘the Rev Mr Gayer is preparing the foundation for a lighthouse at the entrance to the Dingle harbour at which he has a number of men employed.’[10]

The construction was timely for in November 1847, another disaster was averted in a ship laden with desperately needed cargo:

Put into Dingle, by stress of weather, on the 7th November 1847, the French brig Leontina, William Morris, master, from Galatz, in the Mediterranean, 79 tons register, laden with Indian corn, bound to Cork for orders. Ship and crew are all well. The above vessel was driven into this bay by the violent gale on Sunday last, running before the wind, not knowing where she was, and no pilot able to get on board. Had it not been for the towers built outside the harbour’s mouth by Rev Mr Gayer, in which there are large hands pointing to the harbour, she would have been wrecked on the dangerous bar of Inch.[11]

In total, three ‘lighthouses’ or beacons were reported to have been constructed in the vicinity of Dingle Bay: one at Beenbane, a second at Reenbeg and a third on Carhoo hill.[12] Two hundred men were employed on the towers, giving much needed work during the Great Famine.[13]

On 20 January 1848, two months after the completion of three beacons, Rev Charles Gayer died from typhus fever at his residence, Ballintaggart, Dingle.[14]

Eask Tower

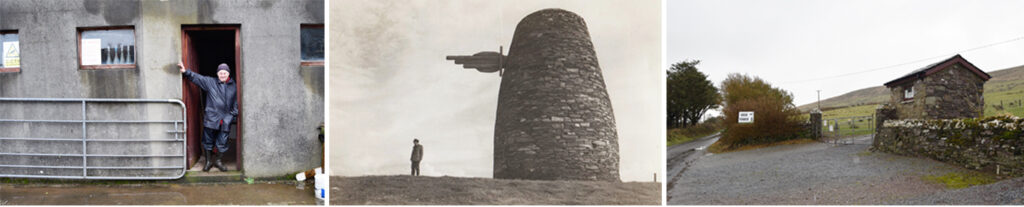

Today, just a small heap of stones remains of the beacon at Beenbane (otherwise Beenbawn) and the construction at Reenbeg has been reduced considerably by the elements. The beacon at Carhoo hill, known locally as Eask Tower or the Mariner’s Beacon, survives relatively intact.[16]

It remains a commanding sight on the journey by road into Dingle. It functions today as a lookout point for visitors wishing to take in the panoramic views of the Dingle Peninsula and beyond. It is on private land, but open to the public.[17]

______________________

[1] ‘The Beacon Towers he had nearly finished to guide vessels to the blind harbour of Dingle are as it were his own tombstones, and will ever remain monuments of his concern for the Roman Catholic poor who alone were employed at them’ (Kerry Evening Post, 5 February 1848). [2] This artistic tribute to Fungi (or Fungie) is held in the archive of Castleisland District Heritage courtesy Marcus Counihan, ref: IE CDH 06. Fungi first appeared in Dingle Harbour in the spring of 1983, discovered by divers Ronnie Fitzgibbon, Tralee and John O’Connor, Beenbane, Dingle. Further reference, ‘Meet Fungi the dolphin,’ Kerryman, 17 October 1986. In 1996 Fungie featured in the TV holiday programme Holidays Out presented by British pentathlete Kathy Tayler. Fungi was last sighted on 13 October 2020. [3] Hampshire Chronicle, 28 January 1788, [4] www.coastguardsofyesteryear.org. [5] Limerick Reporter, 21 January 1840. [6] ‘On the afternoon of 7 April 1845, the dinghy boat of HM steamer, Pluto, was coming on shore with the corporal of Marines and two seamen when a few hundred yards from the coastguard watch-house, the sail jibed and the boat capsized. One of the crew swam to shore but the remaining two were entangled in the boat ... a fishing boat nearby came up to them and were in the act of being taken on board when the chief boatman of the station came up and succeeded in getting the drowning men on board the fishing boat. They were carried into the watch-house and the sailor was saved, but the corporal of Marines did not. The sailors were Edward Launcelott and Thomas Haley. The drowned marine was named Clout. ‘Haley owes in a great degree his preservation to the prompt measure of Edward Stack, a coast guard, who resorted to the means advised by the humane society for the resuscitation of drowning persons’ (Kerry Evening Post, 9 April 1845). [7] Kerry Evening Post, 14 April 1838. ‘This brave fellow on perceiving the great danger of his fellow-creature, immediately descended the precipice and springing into the surge from the lowest spot where he could obtain a floating, swam to her relief, carrying a rope which he tied round her body, and, with the help of two of her brothers, who remained on the cliff, succeeded in bringing her to the summit and thence to her home where she now languishes in a precarious and dangerous state. Ferriter is, we understand, a man of excellent character and served faithfully in the police but was dismissed for taking unto himself a wife without the leave or consent of his superiors.’ [8] ‘In conversation with a gentleman from Dingle, we were this morning informed that for five years past the people of that district have been memorialising the Ballast Board for the establishment of a small light house at the point of the harbour as a guide to the entrance by night. It is a cause of much just complaint that the Ballast Board, one of the richest in the empire, should have so long refused to do its duty towards Dingle. The usefulness of this work is fully proved by the fact that no sooner are these towers erected by the Rev Mr Gayer than they prove the means of saving a vessel from inevitable destruction. For there is no doubt but that the French brig would have gone on Inch bar if it were not for their guidance. But in the darkness of night these towers can afford no protection, so that we would suggest to the Dingle folk to press the Ballast Board again on the subject’ (Kerry Evening Post, 13 November 1847). [9] Kerry Evening Post, 4 March 1846. [10] Limerick Chronicle, 29 September 1847. [11] Kerry Evening Post, 10 November 1847. ‘Had these towers been built, as long since pointed out by Lloyd’s agent, Captain Eagar, many a life and much property would have been saved.’ On November 18 1847, it was reported that ‘Mr Gayer’s Towers are finished. They will, as in the late instance of the French vessel which sailed on Tuesday, prevent the destruction of much life and property’ (Tralee Chronicle, 20 November 1847). [12] As recently as December 1989, a bed of rock was blasted ‘to allow free passage in and out of the harbour for ships’ (Irish Press, 11 December 1989). [13] Tralee Chronicle, 2 October 1847. ‘Dingle. Beacons for the guidance of vessels on entering Dingle Bay and Harbour. There are in being constructed in this locality three solid conical towers, viz, one on Beenbane headland, an excellent commanding position, directing vessels immediately on turning Doulus head into the bay, or as they come west of the Skellig – as the intended tower on Beenban can distinctly be seen even with the naked eye, from either places referred to – another on Reenbeg, and the most southerly point – on the opposite to Beenbane – of the entrances to Dingle harbour, and a third on the highest point of Carhoo hill. These are being constructed under the guidance of Rev Charles Gayer of Ballintaggart; their dimensions are to be almost 14 feet diameter, 43 feet in circumference, and from 30 to 40 feet in length, built of solid dry stone work – when erected to be plastered and dashed with strong lime mortar, white-washed thoroughly round, and on the top of each, there will be erected a mast with a barrel or some other conspicuous object placed thereon. There will also be an iron inserted into the Crow aock (sic), and a boy (sic) suspended thereto. There are 200 men employed on these works.’ [14] Charles Robert Gayer 1804-1848 son of Col Edward Echlin Gayer and Francis Christina Dobbs of Castle Dobbs, Carrickfergus and brother of Arthur Edward Gayer, QC. Short biography in The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry (2011) ‘Parish of Dunurlin’ pp91-96. Ballintaggart House, Dingle, now operates as accommodation and wedding venue on the Dingle peninsula, www.ballintaggarthouse.com. [15] ‘Beacon Towers’ Erected by Reverend Charles Gayer 1847 Entrance to Dingle Harbour from the Joly Collection © National Library of Ireland – Drawn on Stone by Samuel Watson, 17 Richmond Cottages, Dublin. It is not clear if Samuel Watson used artistic license in his illustration or if an additional two towers were erected during the distressed times. Cork City born Samuel Watson (1818-1866) ‘the talented draughtsman,’ died on 22 July 1866 at 4 Bessborough Place, West-road, North Strand, Dublin. He was brother of painter Henry Watson (1822-1911) and uncle of painter Samuel Rowan Watson (1853-1923). Samuel Rowan Watson, son of Henry, was discovered dead in his studio at 34 Upper O’Connell Street, Dublin in November 1923. He was unmarried, and a director of Messrs Boland Ltd and Messrs Duffy and Co publishers. His nephew, George Watson, attended the inquest which found death by heammorhage. Samuel Rowan Watson’s only surviving sister, Helena Watson, died at 79 North Strand on 22 August 1929. Her funeral was attended by nephews and nieces. [16] See Peter Goulding’s blog with images of the remains at http://irishlighthouses.blogspot.com. [17] The facility is currently closed due to the Covid pandemic. An information board at the site reveals that the tower originally stood at 27 feet in height but was increased to 40 feet at the turn of the twentieth century, and furnished with a new hand position near where the extension was carried out. Adjacent to the tower stands a World War II lookout post in precast concrete slabs which was manned by local volunteers to warn of military invasion. On the eastern side of the tower are the remains of a timber Christian Cross set in a concrete base erected in December 1950 to celebrate mass on the hill. It succumbed to rough weather before Christmas of the same year.