‘The Moonlighters were the first that put hope into the nation’

– Memoir of Jerry Lyons, 1951

Castleisland District Heritage this week (19 July 2023) pays homage to Bob Finn, Captain of the Castleisland Moonlighters, at a Grave Renewal Ceremony in Old Kilbannivane Cemetery, Castleisland. The historic memorial has been refurbished, with substantial financial support from John Haniver, Bob Finn’s last surviving grandson. Donations have also been made by the Presentation Convent, Castleisland; Noel Browne, Charlie Horan, Pat Mahony and Denis Divane, Divane’s Volkswagen, Castleisland. The grave renovation has been carried out by O’Connor Memorials, Castleisland, who have kindly sponsored a memorial plaque which will be unveiled during the ceremony.

The name of Bob Finn is today synonymous with the Land War in the Castleisland region. Bob Finn’s remarkable achievements are described by John Roche, Chairman of Castleisland District Heritage, in the following essay:

Late summer 1879 was a horrendous time for the great mass of the common people of Ireland, particularly in the western half of the country. One report is vital to understanding the real misery that prevailed in that, the third year, of what was later described as ‘the three wet years in a row.’ There were 10,000 evictions that year – how many thousands of families were living in fear that their turn was coming up? Seed was scarce and late sown. Weeds dominated over crops and hay or turf couldn’t be saved. Cattle and sheep were pining and dying from malnutrition and parasites, such as Liver Fluke, which thrived on wet conditions. The spectre of Famine was ever more visible, and landlords were on an orgy of rent increases. This orgy was to later prove to be those landlords’ suicide mission – every human has a breaking point, every community too. A large percentage of the ruling Gentleman Class – though not all, it must be said – were completely out of touch with the situation on their great estates, having handed total control to unscrupulous agents. They were only concerned with the gross return in cash on Gale days – tenants weren’t regarded as human beings. The great movement of people power amassed by O’Connell which ran aground through a combination of a physical force movement, organised by dreamers, and the horror of the Great Famine, was still fresh in the collective memory. Two great men from vastly different backgrounds, but patriotic Irishmen, started another mass movement, committed to democratic means, to bring an end to the murderous system that prevailed. Michael Davitt and Charles Stuart Parnell formed the Irish National Land League. Again, the people flocked to the new movement and monster meetings once again became the order of the day. About the same time, three young friends met in Castleisland, namely 19-year-old Robert (Bob) Finn, and his contemporaries, Batt O’Leary and Justin McCarthy. Here we are blessed because we have an authentic written account of the founding of The Castleisland Moonlighters, written 50 years later. It was from the pen of a man whose integrity is beyond question – Timothy M Donovan, East Kerry’s best historian. Timothy was a neighbour, friend and contemporary of Bob Finn. He was unambiguous in his language about the Landlord Class and the culture of the era. He was truthful to a fault, and the only written alternatives are the police and landlord reports, in the mainly Unionist newspapers of the time. The Moonlighters/Land League left no written records. I defer to T M Donovan in his Popular History of East Kerry: ‘One evening in 1879, Robert Finn, then a young athlete of great promise, met two friends of his own age, Batt O’Leary and Justin McCarthy and they asked him to form a secret society:

-

-

For the purpose of freeing Ireland.

-

To help put down land-grabbing.

-

Bob’s leanings were towards Fenianism, but with his trade as a cooper, the rural troubles had his full sympathy. A few days later he consented to form the society, and at a meeting that night in the Cahereens, south of Castleisland town, the Castleisland Moonlighters Association was formed. They swore an oath of allegiance to the captain, and Bob Finn was made the 1st captain of the infant organisation.’ Having made that move, their first objective was to procure arms, and afterwards they became known as ‘The Three Axateers,’ after they raided the police barracks at Farrenabrack outside the town. Their weapons were their father’s axes. They procured eight guns and a bullet mould. There were suggestions that their job was made easy from the inside. The membership mushroomed and Donovan names the original twenty young men who joined, but numbers went far higher than that. Despite his youth, Bob Finn maintained great discipline. Their first Moonlight foray was a journey of about eight miles to East of Scartaglin to reinstate a mother and her family who had been evicted while her husband was in America trying to earn the rent money. Their action was successful and success breeds success, so that Donovan records – ‘By 1881 land-grabbing was history in the Castleisland region.’ ‘Of course, they broke England’s laws,’ wrote Donovan, ‘and they put the fear of God (or is it the devil?) into the hearts of the landlords and land grabbers, but that first company of Moonlighters never committed a dishonourable crime.’ This statement is important. On the 10th of October 1880 at a monster meeting on the Main Street, chaired by the great Land League priest, Fr Arthur Murphy, and addressed by Joseph Bigger MP, who was introduced as ‘the veteran obstructionist of the House of Commons,’ – the Castleisland branch of The Land League was formed. This branch embraced the parishes of Currow, Scartaglin and Cordal, and in tandem with Bob Finn’s Moonlighters, were the leading force of Land Leaguers in the country. The Land League now had what O’Connell’s great movement previously lacked – namely, teeth! Some time later, when Mr Parnell was asked who would take his place if he was arrested, his reply was ‘Captain Moonlight.’ As a result of obtaining those ‘teeth,’ the whole movement was able to employ another devastating weapon – the boycott. With the threat of a Moonlight raid, and being shunned in their community, and publicly shamed at mass meetings of thousands, there were no takers for an evicted farm. It was so simple in hindsight. A phrase from that time – what makes the land dear? When one moves out there’s another ready to move in! Just stop the ‘another’ from moving in and Landlordism is finished. Property without a tenant is just a big liability. ‘Only a madman would risk grabbing an evicted farm and face the wrath of the League and the Moonlighters,’ wrote Donovan. Robert Finn was the original Captain Moonlight of the revolutionary Land War of the 1880s which drove landlordism out of Ireland, bag and baggage, forever. ‘In a short while Bob Finn had imitators in nearly every town in Munster,’ recalled Donovan, ‘without the help of the Moonlighters, Land League meetings, resolutions, speeches and loud cheers, would be unsuccessful against the power of the alien land owners.’ The last dying kick of the disgraced system of Irish Landlordism, cosseted by a corrupt political system, was Mr Forster’s Coercion Bill, when they adopted ‘Internment Without Trial’ into the British legal system. This they implemented for the first time ever in a raid in Castleisland in March 1882. At this stage police numbers in the Castleisland region had mushroomed from about ten to one hundred and fifty. They were dotted around the countryside in ‘police huts’ in a vain attempt to ‘protect’ evicted farms. In the Powell farm alone, a Protestant family whose lands stretched almost to the town boundary on the Killarney road, there were three such huts, but they failed miserably to find a tenant. That eviction was the most gross act of the tyrant land agent, Samuel Hussey. It’s a separate story in itself, as the Powell tenants in a row of thatched cabins had them all razed in a conflagration that left the people with just the clothes on them, while their poultry and small animals went in terror through the countryside. During that first police raid of 1882, they lifted up to twenty of the real leaders of the Castleisland Moonlighters. This included Captain Moonlight, Bob Finn, the chairman of the local League, PD Kenny, the secretary Terence O’C Brosnan, Moonlight vice-captain ‘Major’ Hussey, and many more including many of the recognised leaders. The ‘Major’ Hussey became friendly with Parnell in Kilmainham jail. A number of those interned were close relatives of my late father, including three of his uncles, which gave me an almost first-hand knowledge of much of the campaign. I might add here that in my movements through Kerry, as county chairman of Macra in the 1950s, I was regularly greeted with ‘Castleisland – home of the Moonlighters!’ In honouring the memory of Bob Finn in a Grave Renewal Ceremony, we also place on record the established fact that the Moonlighter/Land Leaguers of the Castleisland, Brosna, Knocknagoshel and Abbeyfeale areas of East Kerry and West Limerick led the campaign that resulted in ending Irish Landlordism, and the tenants in all 32 counties gaining ownership of the properties they occupied. It culminated in the negotiation of very reasonable terms of purchase via a series of Purchase Acts from which we all benefit so much up to this day. We tend to take ownership of our properties for granted, but we should be aware that the Landlord system is still alive and well in much of Britain.

The Land War in Letters

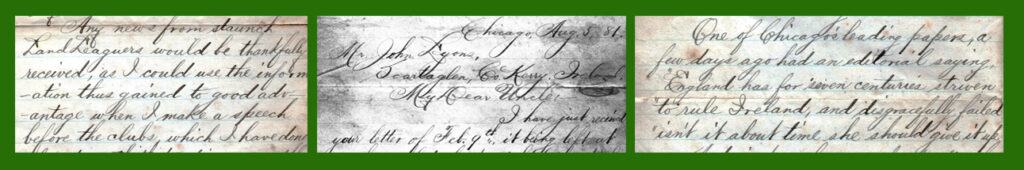

By a strange coincidence, Castleisland District Heritage has been contacted by a local family who have in their possession a number of letters contemporary to the Land War period. They were written by young Irish American, John Douglas Lyons, whose father, James Lyons of Scartaglen, was ordered out of Kerry in about 1854 by landlord, Herbert of Muckross, for shooting game.[1]

James Lyons, who fought in the American Civil War, later died from deprivation in Camp Douglas Prison, his wife only able to identify his remains by a ticket with his name on ‘tied round his neck.’[2] James Lyons schooled his young son against English policy well as demonstrated in young John Douglas Lyons’s fiery correspondence home.[3] Writing from Chicago to his uncle in Scartaglen on 4 November 1881, he declared:

God Speed the day of vengeance upon the heads of those who are the cause of our people being so widely scattered as wanderers over the face of the earth! I hope you are doing your share in the noble work and brotherly struggle which is going on in your poor downtrodden country … keep your mind centred on the men who today linger in sickening cells for the cause of downtrodden humanity … pray fervently and work strenuously to have the end for which Davitt, Parnell, Dillon and other noble souls struggled, brought to a successful termination.

Writing again on 19 May 1882, he hoped that Daniel O’Connell’s words would ‘yet be proven true,’ and underscored the support that America offered to Ireland:

‘No honest man ever despaired of his country, for as sure as tomorrow’s sun will rise, Ireland will yet be free.’ God grant that the near future has that bright boon in store for your poor downtrodden country … as long as she keeps the cradle-land of 10 millions of America’s citizens in chains just so long will we here in America struggle to assist the Land League and like efforts in attempting to wring justice from that stupendous structure of villainy, the landlord system of Ireland, and its partner in crime the British government.

John Douglas Lyons believed Davitt to be ‘the Moses that is destined to lead the people out of the darkness of slavery and if ye only stand by Parnell and him.’ He also believed that ‘God will bless the land of Ireland and drive out the tyrant of landlordism.’

In another letter, John Douglas Lyons speaks of his poor health. His fate is given in an unpublished memoir written in 1951 by Jeremiah Lyons:

John was a great young Irishman, and he mentioned in a letter one time that folks there said to him he worked too hard for a country he never saw. It was the days of the Land League at home, and in America, they had eighteen Land League clubs in Chicago. John met Michael Davitt, and every nationalist from Ireland who went to Chicago, he was a great speaker, spoke at several meetings in Chicago, he wrote some lovely letters home, and sent several papers of his meetings and speeches. He was wonderful, with a youthful appearance. He died in Chicago in October 1882 aged 22 years. We got a Chicago paper with two columns of praise: ‘The sad loss of a young hero’s death.’

With men like Bob Fiun at home working in unison with men like John Douglas Lyons overseas, the fate of Irish landlordism was firmly sealed.

___________________________

[1] Unpublished Memoir of Jeremiah Lyons (1951). ‘James, the eldest son, had to emigrate to America very young. He never done anything but shooting, every day while game season was open, game was plentiful in them days, he was summoned several times for shooting in preserved places, the landlords wanted all things for themselves. It was given in Castleisland court by a gamekeeper who swore young Lyons would shoot the devil. His mother was notified by landlord Herbert of Muckross if she did not send him out of the country she would be evicted from her home for Lady-day 25th March and a letter back from him to be taken into his office to prove he was gone. That was landlordism in Ireland in them days, to be evicted out of a house she built herself, the landlord never lost a penny to, he was boss. James had to go, he got on top of one of Bianconi’s coaches at the cross before day one morning for Cork and Queenstown about the year 1854, the coach was running from Tralee to Cork at the time, and his first letter had to be sent into the estate office. He settled in Chicago.’ [2] Unpublished Memoir of Jeremiah Lyons (1951). ‘My uncle Jim lived for some time in Chicago, got married to a Fitzgerald girl, he then went to the Southern States. At that time you could get all the land you wanted from the government for very little money. He bought up a great deal of land, lived among the native Indians, and would have made a fortune. The Civil War broke out, he was in the South, and he joined the Southern Army (of course he had to). South and north fought for years, the north won, he was taken prisoner. He would not take an oath of allegiance to the north, he claimed they would have all his land and money. He was confined in a prison camp named Camp Douglas Prison, where he died after some time from hunger and dirt. His wife went to get his remains, she would not know him only for a ticket tied round his neck and his name. He had several escapes during the war. He was captain in a cavalry regiment, there were two horses shot dead from under him, and he got through the whole war unharmed with the exception of a slight wound in the face from a shell, only to die from dirt and hunger.’ [3] Unpublished Memoir of Jeremiah Lyons (1951).