‘A fascinating house of indeterminate origins’[1]

Kilmurry House, located a few miles from the town of Castleisland in the parish of Ballincuslane, was built about 1839 by Rev Archibald Macintosh as a Church of Ireland rectory.[2] This three-storey dwelling, with entrance set on the side, basement, four bays on south front, and hipped roof, was evidently a work of restoration, as architecturally it suggests an earlier date.[3]

An entry in the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage describes the house thus:

Detached three-bay two-storey over part-raised basement house with three-bay south elevation, built c. 1835, possibly incorporating fabric of earlier house, pre-1726. Now vacant and partly derelict. Hipped slate roof with overhanging plastered eaves. Painted rendered rubble stone walls. Timber six-over-six pane sliding sash windows with limestone sills. Round-headed staircase window. Round-headed door opening having limestone ashlar Ionic doorcase with fragments of wrought-iron decorative fanlight, approached by flight of steps. Panelled window shutters post c. 1835 to interior. Detached eight-bay two-storey stone-built outbuilding, built c. 1835, to west on an L-shaped plan about a courtyard comprising three-bay two-storey block with five-bay two-storey range at right angles to east; now disused. Gateway to courtyard comprising pair of rendered piers with elliptical-headed carriage arch to centre having connecting screen wall to north.[4]

Kilmurry Castle (Bhaile an Chaisleain)

Parliamentary forces attacked Kilmurry Castle and other strongholds in the vicinity in 1650.[5] Two centuries on, John O’Donovan, in his Ordnance Survey Letters, discoursed on the ruined Kilmurry Castle and observed that it once consisted of three divisions, court, and two castles, ‘of which one was attached to the east end of the court and the other ran collaterally from the south side wall being attached to it.’

It may be speculated that Kilmurry House occupies the site of the second castle. Fitzgerald of Kerry (2018) tells of the bravery of Fitzgerald of Kilmurry Castle in rescuing his love, the beautiful Eva O’Connor, from the nearby besieged Ballymacadam Castle. It is but a sideways glance at the history of Kilmurry Castle, explored to some degree by Castleisland District Heritage in Kilmurry Castle, Castleisland: In Search of its History.[6]

In Discovering Kerry: its History, Heritage and Topography (1976), T J Barrington writes:

Kerry gives us no example of a 16th – 17th century manor house, but there are two good examples of a domestic wing attached to an earlier castle, a feature of the period 1600-1640 but that lasted well into the last quarter of the century. Of these the better is that attached to a tower house at Kilmurray, Cordal, Castleisland. This is a fine house, now much ruined, that shows in striking manner the transition from the castle to the great house, but still heavily influenced by the castle tradition. It is typical of a style dating from the first half of the 17th century.[7]

Rev Archibald Macintosh

Rev Archibald Macintosh, who built Kilmurry House c1839, was appointed rector of the parish of Ballincuslane in November 1836.[8] His ministerial career seems to have begun as rector of Dunurlin where due to absenteeism, his reputation suffered during the Tithe War.[9] He was at that time resident in Tralee where he was curate of the Tralee union of parishes.[10]

Rev Macintosh was an advocate of the Kerry Auxiliary branch of the Hibernian Bible Society.[11] In 1840, speaking at the society’s annual meeting, he calculated that ‘more bibles had been distributed during the past year than any preceding year.’[12] In 1841, Rev Macintosh prepared a sermon for the Triennial Visitation of the Lord Archbishop of Dublin to Killarney. However, ‘the greatest disappointment was experienced in consequence of his Grace having dispensed with that portion of the service’:

Whatever may have been his object in preventing the Rev Gentleman’s preaching, is best known to his Grace but we feel bound to tell him that his mandate was anything but agreeable to the assembled clergy or to the numerous and respectable lay congregation who attended for the purpose of hearing the Rev Gentleman’s sermon rather than his Grace’s hacknied charge on Church Government.[13]

In October 1842, as part of the proselytising movement, Rev Macintosh numbered among those who attended the ceremonial opening of a school-house and place of worship erected ‘for the instruction of those poor people in the vicinity of Feale Bridge’:

Rev Mr Norman, curate of Abbeyfeale, and under whose spiritual care the converts at Feale Bridge have, at their earnest request, been placed, proceeded to read a portion of the Book of Common Prayer in Irish, the entire body of the peasantry in the room, at the windows, and at the door, joining in the ‘responses.’[14]

Rev Macintosh was awarded a grant by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to rebuild the parish church and a subscription fund was set up, to include a school-house.[15] Donations poured in. The long list of subscribers included Lady Headley, Lady Olivia Bernard Sparrow (née Acheson), the Dowager Countess Harberton, the Dowager Lady Godfrey and Rev Arthur Blennerhassett Rowan.[16] As the project progressed, a contribution was made by Her Majesty, Queen Adelaide, the Queen Dowager, forwarded to Rev Macintosh by the Hon William Ashley, Her Majesty’s Treasurer.[17] Proposals for rebuilding the church were sought early in 1844 and the work got underway soon after.

Unfortunately for Rev Macintosh, the Great Famine would reduce his plans for progress and education in the parish, as his attentions turned to alleviating the suffering he witnessed. At a meeting of the Castleisland Relief Fund in May 1846, it was noted that a shop for the sale of Indian meal had been opened in the village of Scartaglen at his motion.[18]

Some months later, Captain Fairfield informed the Tralee Board of Guardians that there was not ‘six pecks of sound potatoes in the entire parish of Ballincuslane.’[19] Rev Macintosh organised a fund for the poor; among those who donated were The Society of Friends, the Peas and Rice Fund, and the Irish Relief Association.[20]

Bryan MacMahon, author of The Great Famine in Tralee and North Kerry (2017), writes:

A meeting of landlords and ratepayers was held in Castleisland in September 1847. It was convened by Rowland Bateman of Oakpark, Tralee and the chairman was Charles Fairfield. The object of the meeting was to find some means of employing the starving poor. Many Protestant and Catholic clergymen were present, including Rev Macintosh and Fr O’Leary. An unnamed reporter began by stating that language was inadequate to describe the condition of the people now that all relief had ended: ‘Verily it is not in man to consider without instinctive horror the awful calamities that appear looming in the distance. Only imagine whole families, numbering several thousands, without the smallest earning, without a rood of land to supply food, without shelter from the approaching winter, without a covering save a few rags which leave them almost in a state of nudity, without a hope on earth save in the Almighty, and you have an exact picture of the misery and desolation which pervades this locality, but more particularly on the mountainous districts of the Ballincuslane electoral division.’

The Tralee Chronicle recorded that Rev Macintosh addressed the meeting, saying that the people were living on cabbage, and many did not even have that.

In February 1848, Rev Macintosh attended a meeting of the tenant farmers in Castleisland for the purpose of ‘earnestly soliciting the cooperation of the Landed Proprietors of those districts by procuring employment for the destitute poor.’ A unity of faith was evident when Rev Jeremiah O’Leary, parish priest of Castleisland, entered the meeting room ‘leaning on the arm of the Rev Archibald Macintosh.’ Rev Macintosh praised the work of Fr O’Leary and acknowledged the patience and endurance of the people.[21]

Tragically, Rev Macintosh was to fall victim to the times. He had been in good health, and active, up until a week before his sudden illness. He had visited a cabin which housed a sick family in the locality.

Rev Macintosh died at Kilmurry House on 29 November 1848, just as his church was completed. He was in his 46th year:

We have seldom had to communicate a more startling announcement than this, or one which will take those of his friends, who might have seen him in the course of a short week before his death, in full health, and with every prospect of a long and useful life, with greater and more afflictive surprise. Mr Macintosh’s disease was malignant fever, caught, as is too probable, in visiting the cabin of a sick family near his house, and which terminated fatally after little more than seven days’ illness. To the poor of his immediate neighbourhood, his loss will be severely felt.[22]

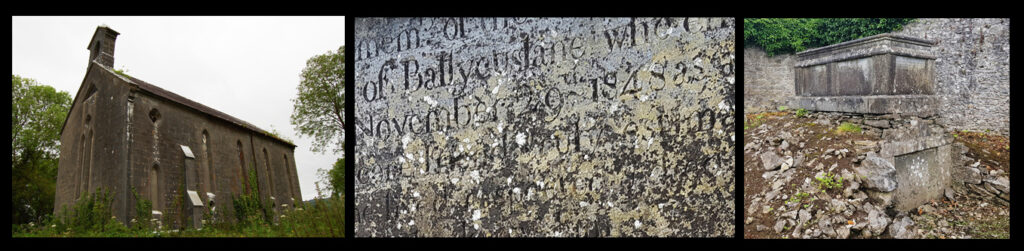

Rev Archibald Macintosh left a widow and young family. He was laid to rest at Ballyseedy, his tomb inscribed:

Sacred to the Memry of the Revd Archibald Mac intosh Rector of Ballycuslane who Entered to his rest November 29th 1848 a faithful Minister and a sincere friend truly estimable in every relation he lived respected and died loved by all who knew him This tribute of affection is raised by his afflicted widow in the assured hope that as Jesus died & rose again Even so them also which sleep in Jesus shall God bring with him Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord that they may Rest from their labours & their works do follow them

Two years after the death of Rev Macintosh, at a dinner held in Castleisland to honour John Sealy, Chairman of the Tralee Board of Guardians, Fr Jeremiah O’Leary, parish priest of Castleisland paid tribute to the work and collaboration displayed by local clergymen during the Famine years. He remembered his friend Rev Macintosh:

Of Mr Macintosh, I will say he always went heart and hand with me. Living, I loved him as a dear friend, and lamented him in death. I think his death has left a vacuum in society which many a long year will not fill.[23]

The Family of Rev Archibald Macintosh

The Macintosh family and relatives continued to be associated with Kilmurry House to some degree throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, and into the early twentieth century.[24]

Rev Macintosh married Catherine Frances Basil Raymond (née Rowan), widow of Samuel Raymond Esq of Ballyloughrane House, Co Kerry, and mother of Anthony Raymond (1816-1895), George Raymond QC (1818-1889) and Samuel Raymond (b1820).[25] The marriage took place at Molahiffe Church of Ireland in May 1828. They had six known children, the youngest, a daughter, born at Kilmurry House in the year of her father’s death.[26]

It is not clear if Catherine Frances Macintosh remained at Kilmurry House with her family in the years after her husband’s death, but it would appear so.[27] She died at Kilmurry on 30th October 1864 aged 65 and was buried with her husband in the family vault at Ballyseedy:[28]

Sacred also to the memory of Catherine Frances Macintosh who died 30 Oct 1864 aged 65 years To her to die was gain Her children arise up & call her Blessed Prov 31 : 28[29]

Kilmurry House was subsequently let at various intervals by second son, Robert Macintosh Esq, and his half-brother, George Raymond Esq.[30] Eldest son, Moore Morgan Macintosh (1829-1853), entered the ministry. He was ordained at Litchfield for the curacy of Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire, in June 1852. The following year, he was drowned while bathing at Nailor’s Hole, Sandycove, Dublin, during a visit to his mother. He had officiated at Dalkey Church on the Sunday previous to his death, the only occasion on which his mother had heard him preach.[31]

Third son and namesake, Archibald Macintosh (1837-1905), joined the Royal Marines. He was appointed to cadetship on board the gunnery ship Excellent at Portsmouth in 1854. His career progressed rapidly. In 1855, he was appointed second lieutenant and in 1858, first lieutenant. He gained the rank of Captain Royal Marine Light Infantry in 1867, and Major in 1878, retiring in 1880 with the honorary rank of Lieutenant Colonel. In 1869, Captain Archibald Macintosh married Mary Anne Taylor Fitzmaurice (1836-1924), widow of the Hon Frederick O’Bryan Fitzmaurice, Commander RN, son of the Earl of Orkney.[32] Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Macintosh died at Fordelands, Newton Abbot on 5 January 1905 aged 67.[33]

Catherine Frances Macintosh (1831-1908) was the eldest daughter of Rev Macintosh. Little appears on record about her life. She died at Kilmurry House on Good Friday 17 April 1908 and was interred in the family vault at Ballyseedy.[34] Second daughter, Agnes, was born in Tralee in March 1834[35] and youngest daughter, Mary De Courcy Macintosh, was born in 1848.

Mary contributed items of historical interest to the Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead in Ireland.[36] In 1909, she applied for and was awarded compensation for the destruction of ornamental trees and a damaged boundary wall at Kilmurry. During the hearing, it was revealed that John Connor was caretaker there, and that the damage was caused to prevent the sheriff and his men from passing through.[37] Mary De Courcy Macintosh, spinster, of 39 Mount Pleasant Terrace, Dublin, died on 22 November 1936 aged 89.

The O’Mahony of Kerry

George Raymond, BL, bequeathed Kilmurry House to Peirce Gun Mahony, BL (1878-1914), elder brother of Dermot Gun Mahony (1881-1960), Fine Gael TD for Wicklow.[38] George Raymond was the second husband of Martha Jane (Montgomery) Collis, Peirce’s maternal grandmother.[39]

Peirce and Dermot were sons of Peirce Charles de Lacy Mahony MP, ‘The O’Mahony of Kerry’ – who assumed the name O’Mahony by Deed Poll in 1900.[40] Peirce Charles de Lacy Mahony (1850-1930) and his brother, George Philip Gun Mahony DL (1842-1912) of Kilmorna, Listowel, were half-siblings of Edith Jane Matilda Vicars (1857-1930), Major William Henry Vicars (1858-1942), Dr Frederick George Vicars (1860-1924) and Sir Arthur Edward Vicars (1862-1921) from their mother’s second marriage, in 1856, to Col William Henry Vicars (1800-1869).[41]

1n early January 1905, Sir Arthur Vicars, accompanied by Peirce Mahony of Kilmorna House visited Brosna in the course of research of the O’Mahony family:

The party, accompanied by Sergeant J Lyons, RIC, and a number of townspeople, visited the local graveyard and inspected the tombstones therein. They succeeded in deciphering sepulchral inscriptions of considerable antiquity, and were supplied with a good deal of genealogical information by a few of the townspeople.[42]

In 1909, Richard Walsh, one of the tenants on the Kilmurry/Mahony estate, was evicted in what would become a public and long running stand-off between landlord and tenant. The affair became known as ‘Walsh’s Fort.’ [43]

In 1913, John Walsh of Kilmurry, in the employment of Mr Mahony, summoned Patrick Connor for obstructing him on a public road.[44] Patrick Connor counter-sued. The episode highlighted deteriorating relations between landlord and tenant.[45]

Peirce Gun Mahony married Ethel Tindall, youngest daughter of John James Wright, MD, of Campfield House, Malton, Yorkshire. The ceremony took place at St Augustine’s Church, Queensgate, on 26 November 1903. The marriage was short lived; Peirce died as a result of a shooting accident at Grange Con, Co Wicklow on 26 July 1914.

Sympathy was extended to Ethel, his widow. The inhabitants of the Kerry parish of Brosna held a public meeting to prepare an address:

Hundreds of years ago, the townland of Brosna was the ancestral home of one branch of this powerful sept, and their old graveyard here, beside where they stood, held inscribed testimony on its tombstones dating back to the year 1741. The great and princely O’Mahonys held sway in Brosna and surrounding districts in the good old days before Ireland was crushed by the unjust laws of her invaders. Hence Brosna was originally known at The O’Mahony country … We express our deepest and heartfelt sympathy to The O’Mahony of Kerry over the sad accident that caused the death of his dear son, also to his bereaved widow, Mrs Pierce Gun Mahony, Kilmurry House, and also to his uncle, Sir Arthur Vicars, KCVO, of Kilmorna Castle.[46]

On 4 July 1917, at the age of 53, Sir Arthur Edward Vicars, one time Ulster King of Arms and Keeper of the Irish Crown Jewels at Dublin Castle – stolen during his custodianship in 1907 – married Gertrude Williford Wright (1854-1946), sister of Mrs Ethel Mahony, at Grange Con, Co Wicklow.[47] The bride’s address on the marriage certificate was Kilmurry, Castleisland. Mrs Ethel Mahony acted as hostess in the celebrations.[48] She returned to Dublin the same evening, but died suddenly on Friday 6th July. Her remains were laid in the private chapel at Grange Con before burial at Ballynure Church.[49]

The premature deaths of Peirce Gun and Ethel Mahony occurred during the Irish Revolutionary period, one which included the capture, at Kilmurry House, of Republican Jeremiah O’Leary who was taken to Castleisland and shot.[50] On 14 April 1921, Sir Arthur Vicars was shot dead by the IRA at Kilmorna House, and the property totally destroyed by fire.[51]

The family links forged between Kilmurry House and Kilmorna House led to speculation that the Irish Crown Jewels were hidden at Kilmurry Castle – the ruin generally believed to be connected by tunnel to Kilmurry House.[52] Stories emerged about people dressing up in the jewels near the castle, which stands within view of Kilmurry House.[53]

Kilmurry House Post Independence

Edith Jane Matilda Vicars, sister of Sir Arthur Vicars, married Daniel Joseph de Janasz of Wolica, Poland. As the Macintosh-Mahony era drew to a close, the de Janasz Estate at Listowel was divided by the Land Commission in 1928/1929.[54]

Various owners occupied Kilmurry House in the years that followed, including the families of Walsh, Brosnan and Hill.[55] Its current owner, Caroline Faulkner, who purchased the property about fifteen years ago, has rescued the house from ruin and is restoring it.

_________________________________

[1] Houses of Kerry (1994) by Valerie Bary, p158. [2] ‘Situated on the S. end of the Td. Of Kilmurry and W. of Ballycushlaan [Kilmurry] Castle. This is a handsome House the seat of the Rev. Archibald McCa(n)toss, who is Rector of the Parish, and built by him in 1839 and is three story (sic) high’ (Ordnance Survey Name Books). [3] Ibid. It does not appear to have been a Church of Ireland property as it remained in the family of Rev Archibald Macintosh. In all likelihood it was alluded to as a rectory by association. [4] Reference courtesy Jane O’Keeffe, Irish Life and Lore. The current owner of the house, Caroline Faulkner, made the following observation by email to Janet Murphy on 5 May 2021: ‘Kilmurry is unusual as it is asymmetrical. It is definitely Georgian and probably only later on in the 1800s was restored for use by Rev Archibald Macintosh from its dereliction … original thin-glazed windows have been found in the walls which have 1mm glass as befitting Georgian eras. Georgian houses were always in symmetry … The 83.5 ft Cedar of Lebanon in front of the rectory blew down and uncovered a cave with a smelting ring.’ Caroline attributes the survival of Kilmurry to its use as an IRA safe house: ‘Prisoners were kept in the jail which was a piggery previously … a little girl burned to death in the byre house which is still extant … The castle has a tunnel between it and Kilmurry. The Kilmurry Hoard in the National Museum was found by Joe Brosnan and his father in 1948 at the cave, now covered up.’ In a later email (28 March 2022) Caroline comments on Kilmurry’s Neolithic importance: ‘The early Halstatt settlers in Kilmurry, especially in the front field, were immigrants from what is now Austria and Switzerland, they undoubtedly had structures there first, and their culture yielded the Kilmurry Hoard, now in the National Museum of Dublin … this bronze work settlement shows human occupancy over thousands of years in this same spot which is riddled with cave systems leading up to Crag Cave … the hoard was found by Joe Brosnan and his father in 1948 at the mouth of the cave opposite the Music Hole cavern entrance. It is likely the Kilmurry spot was initially a devotional place to Isis due to its orientation towards the moon's (feminine divine) apex … the present house faces away from the roads and towards cairns on the hill horizon. This being a pagan goddess, the name of the fields were likely changed to Cill Mhuire (Mary) during the Catholicism roll out over later centuries, as often Isis sites were appropriated to the more acceptable Mary figure who was similarly the Queen of Heaven ... the current Kilmurry grotto was built over this cave's entrance in the 1950s, blocking it up, an act which tends to support this theory of suppression/name change … There is a much earlier building under Kilmurry and recently we found musket-balls from the 1600s which seems to attest to the fighting and the probable razing of the first house in the Cromwellian era.’ [5] Kilmurry (Kilmurray) Castle, otherwise Bhaile an Chaisleain (Ballycuslane Castle). See spelling variations, ie, Ballycushlane, Ballycushlaan, Baile an Chaisleain, Ballinguishlane, Ballyguishlane at logainm.ie. [6] The Ordnance Survey Name Books give the following account of Kilmurry Castle in the early 1800s: ‘Situated in the S end of the townland of Kilmurry and E of Kilmurry House. This castle is in ruins it was once the seat of a man of the name of Fitzgerald, who had 3 other Brothers, one of which lived in Ballyplimmoth Castle and another in Ardnacragh Castle. There was such malice and enmity subsisting between those Brothers, that one dare not walk through the others land or premises, but should go round, even going to Divine Service.’ [7] The second example of a domestic wing attached to an earlier castle is at Ross Castle, Killarney. Reference courtesy Jane O’Keeffe, Irish Life and Lore. [8] Spelling variations include Ballycushlane and Ballycuslane. See The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry a record of church & clergy in the nineteenth century (2011) for further reference to the clergy of Ballincuslane. [9] ‘On Wednesday last, the whole male population of the parish of Ferriter appeared in Dingle before P B Hussey and Robert C Hickson, justices of the peace, in answer to summonses at the suit of the Rev Archibald Mackinsosh (sic), served on them some days before, by George Boyle and Daniel Crean, under the escort of Major Mullins, and a party of the military. Lord Althorpe’s plan respecting tithes was announced in court to the defendants and likewise that it was the opinion of the bench that their parish should be amenable to £260 per annum ... There is neither a church nor a Protestant in this parish except a Mr Gubbins who was lately sent there as curate to keep appearances, and read divine service to a few English Waterguards at an adjoining station. The Rev Archibald Mackintosh, the incumbent, resides in Tralee, and claims the above sum for the spiritual consolation, which he has never occasion to administer’ (Tralee Mercury, 26 June 1833). Further reference to Rev Gubbins in The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry a record of church and clergy in the nineteenth century (2011), parish of Dunurlin, pp91-96. [10] The Church of Ireland in Co Kerry a record of church and clergy in the nineteenth century (2011), pp32-33. ‘The Protestants of Tralee have presented a tea service of plate to the Rev Archibald Macintosh on his departure from that town and promotion in the church’ (Address and response outlined in Kerry Evening Post, 16 November 1836). At this time the rector’s residence was ‘The Spa.’ In 1831, Rev Macintosh performed the marriage of Thomas Trant Esq of Dingle to Mary Anne, eldest daughter of Pierce Chute Esq of O’Brennan in Tralee Church and in 1835, at Ballymacelligott Church of Ireland, of George B Woodley Esq of Ballymallis Cottage to Helena, eldest daughter of late John Drew Esq of Rockfield. [11] The Hibernian Bible Society was established under the title of Dublin Bible Society in 1806, its object ‘to circulate the Holy Scriptures through Ireland.’ It changed its title to the Hibernian Bible Society on 25 February 1808 in order to extend the society throughout the country. The Kerry Auxiliary branch of the Hibernian Bible Society was established during a meeting in Tralee on 11 October 1814, John Bateman Esq, Oakpark, in the chair, and Rev Messrs Benjamin Williams Mathias and William Thorpe, secretaries, Dublin, assisting. Mr Thorpe, from ‘the scarcity of bibles and testaments in Ireland,’ demonstrated the need for the Bible Society and addressed the ladies present to ‘influence and support the sacred cause.’ Two societies formed, ‘one of ladies, and the other of gentlemen, comprising all the rank and respectability of that highly respectable part of the country’ (London Moderator and National Adviser, 7 November 1814). [12] Kerry Evening Post, 13 May 1840. [13] Kerry Evening Post, 1 September 1841. The Lord Archbishop, Richard Whately (1787-1863), was guest of Rev Richard Herbert of Cahirnane House, Killarney. [14] Full report of the opening in Kerry Evening Post, 12 October 1842, ‘Triumphs of God’s Word in the Irish Tongue – Reformation in Kerry and Cork.’ A congregation of between thirty and forty was reported the following year when an appeal for funds was made. The converts were under the care of Rev Edward Norman, who had been appointed rector of Brosna (Statesman and Dublin Christian Record, 9 June 1843). Further reference to the subject of conversion in Faith and Fury The Evangelical Campaign in Dingle and West Kerry 1825-45 (2021) by Bryan MacMahon. [15] The following reference is courtesy Jane O’Keeffe, Irish Life and Lore: The importance of an early church in Kilmurry in the far distant past, are illustrated in an interesting entry in the 1906 edition of the Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland written by Rev. James Carmody P.P. under the heading: The Abbey of Killagha, [Milltown] County Kerry: In the “Papal Taxation” of 1302, Killagha is rated as the third highest of all the religious establishments in the Diocese of Ardfert … [The Bishop] had three sources of income which were severally taxed… Revenue [offerings made to the cathedral church] was valued at £32; Procuration [offerings from incumbents of parishes visited] £10; Administering of justice £7 13s 4d. Next was the Ecclesia Nova, valued at £5. The late Father Denis O’Donoghue, P.P., believed that this was the church of Kilmurry, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, in the townland of Cordal, east of Castleisland. It must have been noted as a place of pilgrimage, and in receipt of a large revenue from the offerings of the pilgrims. [16] Kerry Evening Post, 26 July 1843. Dowager Viscountess Harberton was Elizabeth, daughter of Thomas Kinsley Esq, drug merchant and High Sheriff of Dublin 1799-1800. She married in 1800 the Hon Arthur James Pomeroy (1753-1832) 3rd Viscount Harberton, and was noted for her ‘numerous acts of benevolence and philanthropy.’ Elizabeth, Viscountess Harberton, died at her residence, 54 Summerhill, Dublin on 10 November 1862. See Henry Pomeroy (1723-1798), Viscount Harberton, in A Biographical Peerage of the Empire of Great Britain (1817) by Sir Egerton Brydges, pp275-276. Lord Harberton of Carbery, Co Kildare, was advanced to Viscount Harberton in 1791. He died on 9 April 1798 and was succeeded by his eldest son Henry (1749-1829), 2nd Viscount Harberton who left no surviving issue by his wife Mary, daughter of Nicholas Grady Esq of Grange, Co Limerick. Succeeded by his brother, Arthur James Pomeroy (1753-1832), 3rd Viscount Harberton, Dowager Lady Godfrey was Eleanor, wife of Sir John Godfrey, 2nd Baronet and mother of Sir William Duncan Godfrey, 3rd Baronet. Eleanor was the daughter of John Cromie Esq of Cromore House, Portstewart. The death in Kerry of Dowager Lady Godfrey, at the age of 81, was announced in early September 1852. [17] Kerry Evening Post, 2 December 1843. Queen Adelaide, the Queen Dowager (1792-1849). Adelaide married King William IV (1765-1837) in 1818. [18] Kerry Evening Post, 19 May and 9 September 1846. [19] Kerry Evening Post, 9 September 1846. Further reference to Major Fairfield in Philip of the Hundred Cows, a folk tale from Cordal (2015). [20] Kerry Evening Post, 31 March 1847. [21] Tralee Chronicle, 5 February 1848. [22] Kerry Evening Post, 2 December 1848. ‘By the inhabitants of this town [Tralee] his memory will be long remembered with respect and affection, as their faithful minister for many years, until advanced by his bishop to the Rectory of Ballincuslane, where his exertions had just completed the erection of a church, and where there was every prospect of his ministry and residence being eminently useful. It pleased his Master to call him hence, most unexpectedly to his friends and sorrowing family, while to himself his early death is ‘rest from labour’ and the ‘great gain’ which is the portion of those who ‘depart hence in the Lord.’ [23] Writing in The Great Famine in Tralee and North Kerry Bryan MacMahon tells us that the population in Cordal West in Ballincuslane parish fell from 512 to 97 during the years 1841-51, a decrease of 81 per cent. [24] In 1887, an inquest was held at Kilmurry House on the body of John Leary, a local man shot dead by emergency-man, James Edward Fisher. John Leary was shot in the vicinity of the house on 5 January 1887. Fisher was caretaker of a nearby evicted farm and claimed to have fired the shots in self defence. He was tried in July, found not guilty, and discharged. [25] The tomb of Mrs Macintosh at Ballyseedy records the death of eldest son, Anthony Raymond, who died at Kilmurry House on 25 November 1895 aged 79. The death of Samuel Raymond Esq of Ballyloughran, at the seat of his son-in-law, George Rowan Esq, Ratanny, was recorded in the Cork Constitution, 27 January 1827. [26] Mary de Courcey Macintosh, born on 26 February 1848. [27] Griffiths Valuation records her resident at Kilmurry and places a value on the property at £50. She also leased a house, offices and garden to John Walsh Jnr valuated at £1.10.0 and a house to Thomas West, valuated at 7 shillings. [28] ‘On Sunday last, after a long and painful illness, at her residence, Kilmurray, near Castleisland, aged 65 years, Mrs Francis Mackintosh, relict of the late Rev Archibald Mackintosh, rector of Ballincuslane’ (Kerry Evening Post, 2 November 1864). [29] A second panel is inscribed: And her eldest son Anthony Reymond (sic)/Died Novr 25th 1895. [30] Kerry Evening Post, 16 November 1864. ‘Interested parties should apply to Robert Macintosh Esq or to George Raymond Esq, Great George-street, Dublin.’ Robert Macintosh, second son of Rev Macintosh, was born in 1832 and married Catherine, daughter of John Buckley, in Killarney Church of Ireland on 14 December 1876. Mary Gertrude Macintosh was born in 1877, the same year in which Robert Macintosh of Kilmurry, Castleisland, was adjudged bankrupt. [31] His death occurred on 28 June 1853 at age 24. He was buried at Mount Jerome cemetery. Report of accident and inquest in Nenagh Guardian, 6 July 1853. [32] Commander the Hon Frederick O’Bryan Fitzmaurice, RN, third son of the Earl and Countess of Orkney, died at Bangor on 26 October 1867 aged 38 whilst in command of the coastguard station there. He married Mary Anne Taylor, eldest daughter of Robert Taylor S Abraham Esq and grand-daughter of Rev Richard Abraham, Rector of Chaffcomb, and Vicar of Ilminster, Somerset, at Countess Weir, Exeter, on 19 April 1853. [33] Lt-Col Macintosh was buried at Wolborough; funeral report Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 11 January 1905. Among the mourners, his daughter, Mabel Frances Raymond Macintosh (1872-1936), subsequently the wife of Commander William Abraham Ludington Quixano Henriques RN (1851-1925) of Newton Abbot; and Mr and Mrs L Fitzmaurice, stepson and daughter. [34] The following inscription is carved below that of Anthony ‘Reymond’: Catherine Frances Macintosh/Eldest daughter/Died April 17th 1908 [35] Perhaps the Agnes Mary Macintosh of Princes Street, Tralee, who died in Tralee and was buried on 2 July 1854. [36] An item about Kilmurry Churchyard was submitted to the journal in 1907 by Miss Mabel Raymond Macintosh (Vol VII, p99). Mrs Mabel Frances Raymond Henriques of Grosvenor House, Grosvenor Place, Bath, died on 27 April 1936, leaving estate £4,763 2s 11d, probate to Lloyds Bank Ltd, sole executor. [37] Damage also claimed by Joseph H Montgomery and C H Monseratt, both of Dublin, for damage caused to dwelling house and out offices at Kilmurry on 22 June 1909. [38] Dermot Gun Mahony married in 1913 to Grace, daughter of James Ledger Hill of Burford, Wilts and Combe Grove, Bath, and had issue one daughter, Helen Lacy, in 1915. Grace died at Grange Con on 2 December 1959 aged 78. Dermot died on 23 April 1960. Buried Ballynore/Ballinure. [39] George Raymond, barrister-at-law, died at 3 North Great George’s-street, Dublin on 21 February 1889 aged 71 years. Funeral to Mount Jerome. The mother of Pierce Gun Mahony was Helen Louise (1853-1899), only daughter and heiress of Maurice Collis, MRIA (1810-1852) and Martha Jane Montgomery (born 1824). Martha Jane (Montgomery) Collis, widowed in 1852, married George Raymond in 1858. [40] Peirce Charles de Lacy Mahony MP was married first in 1877 to Helen Louise Collis who died in 1899. He married secondly, in 1901, to Alice Jane (died 1906), eldest daughter of Lt-Col Francis William Johnstone. [41] George Philip Gun Mahony and Peirce Charles de Lacy Mahony were sons of Peirce Kenefeck (Kenifeck/Kenefick) Mahony (1817-1850), Accountant-General, Court of Exchequer, High Sheriff of Kerry, JP, of Kilmorna and Gunsborough, Co Kerry and of Grange Con, Co Wicklow and Jane Mary (1821-1873), daughter of Robert Gun Cunninghame of Mount Kennedy, Co Wicklow, who married in 1839. Edith Jane Matilda de Janasz (née Vicars) wife of Daniel Joseph de Janasz (1854-1936) of Wolica, Poland, died at Dinard, France, with issue, on 8 March 1930. Major William Henry Vicars, 90th Light Infantry, 2nd Scottish Rifles and The Royal Scots, died on 18th October 1942. He married Edith Chica Sophia Long (1849-1921) in 1912. Dr Frederick George Vicars of Shafte House, Rugby, and of London, died on 4 May 1924 – letters of administration granted to his daughter, Mrs Dorothea Castle, his only next of kin. [42] ‘The party called upon the Rev Father Murphy, parish priest, before departing’ (Freeman’s Journal, 6 January 1905). [43] See ‘Walsh’s Fort Recaptured after 7 Years War’ by John Murphy, Kerry News, 23 February 1916 which gives a summary of the eviction of Dick Walsh in 1909 to the reinstatement of the family in February 1916. A song about the affair by Eugene O’Mara of Ardmona, Cordal, begins: Ye brave boys of Cordal ye made a great stand/Ye worked night and day to keep Walsh in his land, is held in The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0446, pp215-216. [44] There were five unrelated Walsh families in five consecutive farms on the roadside from Kilmurry Cross to Coom. Richard Walsh (Dick Johnny) was the first at the cross; across the road from him was Kilmurry House, owned by Tom (Cragg) Walsh; further up the road towards Coom was Jack Dan Walsh (owned Kilmurry Castle which remains in the family) and next to him, Dick Neddy (Sheheree) Walsh, and in Coom, was Tom Redmond Walsh. Tom (Cragg) and Dick Johnny were cousins. Mai Walsh, the daughter of Tom (Cragg), married Paddy, the son of Dick Johnny. Their son Richard remains on the farm at Kilmurry. Information courtesy John Roche. The relationship between John Connor, caretaker, and Patrick Connor, if any, is not known. [45] During the hearing it was revealed that the men had been acquainted for twenty-five years and Connor had been in the employment of the Misses Macintosh and later Mr Mahony for those years. Connor explained that he had been on good terms with the people of Kilmurry until the eviction of Richard Walsh since when he had been boycotted (Kerry Evening Post, 14 May 1913). [46] Kerry Evening Post, 19 August 1914. [47] Miss Gertrude Williford Wright, Kilmurray, Castleisland, Co Kerry appeared in the list of members of the Irish Georgian Society in 1913 – The Georgian Society Records of Eighteenth Century Domestic Architecture and Decoration in Dublin (Vol 5, 1969, originally printed 1913) with introduction by Desmond Guinness, The Irish Georgian Society. Appendix to the report of the Vice-Regal Commission appointed to investigate the circumstances of the loss of the Regalia of the Order of Saint Patrick, and to inquire whether Sir Arthur Vicars exercised due vigilance and proper care as the custodian thereof: minutes of evidence (1908) was published by the Crown Jewels Commission (Ireland) in the wake of the theft of the jewels. An account of the affair, ‘The Theft of the Irish Crown Jewels, 1907’ was published in History Ireland, Issue 4, Winter 2001. Sherlock Holmes The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans (1908) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle includes a thinly disguised version of events. Irish marriages, being an index to the marriages in Walker’s Hibernian magazine, 1771 to 1812 With an appendix, from the notes of Sir Arthur Vicars by Henry Farrar was published in two volumes in 1897. [48] Maurice O’Keeffe, Irish Life and Lore, has recently acquired the Visitor’s Book for Grange Con, Co Wicklow, which covers the period of c1890s to 1930s. The entry for 4 July 1917 includes the wedding party. A note alongside the signature of O’Mahony states: ‘Ethel was present and gave the tea in gallery after Wedding Service, but forgot to write her name. O’M.’ The signatures include Arthur Vicars and his bride, Gertrude W Wright, signed subsequently Gertrude W Vicars. Among the guests were Norah M Wright, John Pattison, the Dean of Ardfert; William Henry Vipond Barry (1858-1938) of Dublin, organist and choirmaster; Honourable Carroll of Moone Abbey, Moone, Co Kildare and Athelstane George Wolseley (1858-1933) about whom see Patrick Comerford’s ‘A simple inscription that led to stories of theft, scandal, murder and a lost title’ (14 July 2015). [49] Chief mourners The O’Mahony, father-in-law, Sir Arthur Vicars, brother-in-law. Service by Rev A L Rhind, rector, assisted by Rev G Browne, Castleisland. [50] An account of the affair is given in Dying for the Cause (2015) by Tim Horgan, pp218-220. See also ‘Diarmuid Ó Laoghaire / Jeremiah O’Leary (1894-1923)’ on this website (www.odonohoearchive.com), ‘The Republican Monument, Kilbannivane, Castleisland.’ [51] Sir Arthur Vicars was buried at Leckhampton near Cheltenham. Lady Gertrude Williford Vicars of Fairhaven, Walton, Clevedon, Somerset died 16 January 1946 and was buried at Leckhampton. She left estate £21,276 gross. [52] Kilmorna House is named Kilmeany House on the first edition Ordnance Survey map. Nothing remains of the property. [53] Further reference to Kilmurry Castle, see ‘The Cromwellian Butchers’ (Romantic Hidden Kerry (1931) by T F O’Sullivan, p73). ‘In 1650, Colonel Phair, Governor of Cork for the Parliamentarians, took Kilmurray Castle and captured a large number of cattle belonging to the people of the district.’ See also http://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-fitzgerald-castles-of-cordal/ [54] See note 41 regarding Vicars/de Janasz. [55] It is worth noting that Shane McAuliffe of Parknageragh House, Castleisland owns an artefact which once belonged to Kilmurry House. The object, a bird preserved by taxidermy encased in glass dating to c1900, was acquired some years ago from a business in Farranfore.