It is difficult today to imagine how life must have been for the religious in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries during Penal oppression. Glimpses are given in notices from the times, this one from 1650:

All the Papists are to be turned out of the city; and from the Jesuits, priests, friars, monks, and nuns, twenty pounds will be given to any one that can bring certain intelligence where any of them are. And whosoever doth harbor or conceal any of them is to forfeit life and estate.[1]

Irishman Most Rev Patrick Francis Moran, Archbishop of Sydney, writes of the martyred Kerry priest, Fr Thaddeus Moriarty who was executed at Fair Hill, Killarney in 1653, and observes that Fr Moriarty’s father ‘was the head of the sept of the Mac Moriartys whose hereditary possessions lay on the banks of the Mang.’[2]

The landscape of Kerry, ‘its bare and inhospitable mountains, its impregnable position’ made it the refuge of the fugitive or those ‘who sought fame and fortune in the armies of the continent where, as the Wild Geese, they upheld the Celtic reputation for valour.’[3] The same landscape helped to shield the clergy in Penal times:

Many a priest returning from Salamanca, Louvain or St Omers found a refuge amongst the peasantry while waiting for brighter days. These devoted sons of Ireland, men of worldwide culture and fame, had perforce to live the lives and share the privations of the people but if they were denied the right of returning to their native parishes, they well repaid the poor peasants who sheltered them by teaching them and their children with the result that it was commonplace a couple of centuries ago to find poor herdsmen in the Kerry hills who, though ignorant of English, could speak Latin and Greek fluently.[4]

In the 1700s, a report to Joshua Dawson (1660-1725) MP, dated 16 October 1712 from Captain Richard Hedges, magistrate, Macroom, shows the dangers faced by the religious:

Sir – As soon as I received their Excellencies the Lords Justices’ Proclamation about Roman clergy I made search for the priest of the parish, but he having absented himself, I got two of our clergy to go with me to examine his books and papers. We had his doors and trunks opened, but found nothing but a great number of mouldy books, some papers of no consequence to the public, and a parcel of bones made up in a box of cotton with inscriptions of saints names on them … I gave a warrant to the High Constable to bring him and others before me … On my return from Kerry, I found the priest of this parish returned and had him apprehended yesterday and sent him to Cork Gaol after his refusal to take the oath proscribed by the Act. His name is Donagh Sweeney, a doctor of Sorbonne, registered in this parish.[5]

On 2 April 1715, a list of Roman Catholic priests who had not taken the Oath of Abjuration was given at a general assizes in Tralee. In the parish of Castleisland, unregistered priest, Fr Charles Dorane, was recorded as officiating in place of Charles Daly, deceased.[6]

Other local clergymen whose names come down to us include Father Denis Sughrue, born in 1705, ministering in Castleisland c1750; John Mallone (1710-1781), ordained at Douai, was ministering c1761 and Maurice Fitzgerald (1746-1830), who ministered in Castleisland from 1781, when ‘Father Darby’ (Father Jeremiah O’Shanahan,1745-1781) died.

Father Darby Shanahan was appointed parish priest of Castleisland c1774. He had been ordained in the Church of St Nicolas du Chardonnet, Paris, in 1770.[7] Castleisland historian, T M Donovan, in an account of Fr Shanahan’s tomb in St Stephen’s Churchyard, Castleisland, alluded to the Penal Days and how worship was conducted before the erection of Fr Shanahan’s thatched church later in the eighteenth century:

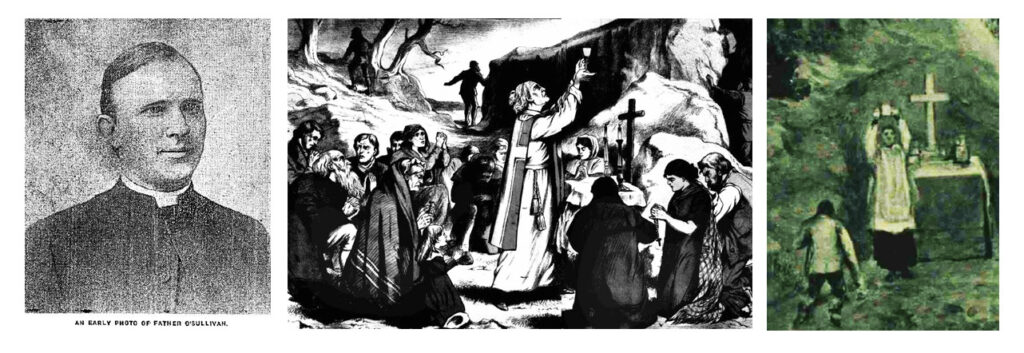

The hunted priests of the Penal days said Mass in the Gloun an Affrins, or Mass Rocks, of East Kerry at Gortglass, Foyle Philip, and Glounaneenta – out in the mountainside, the bog, the glen, the mud cabin or the wood.[8]

In the century that followed, the religious did not forget the plight of their predecessors. On Tuesday May 26th 1903, the Golden Jubilee of Archdeacon Fr John O’Leary (1821-1918), later Right Rev Monsignor John O’Leary, was celebrated. He had been serving the parish of Castleisland since 1894.[9] After High Mass was celebrated in the parish church, Very Rev D J Canon O’Riordan, Parish Priest of Kingwilliamstown, delivered a sermon, a good portion of which alluded to the plight of the clergy in Penal Times:

This summer, fifty years ago, Fr John O’Leary came into this mountainous region of the Kerry diocese. At that time the surroundings of a priest in Ireland were very different from what they are today. The penal days had passed. The priest and the school teacher had been removed from the category of wild beasts whom it was the duty of so-called good citizenship to hunt down and to destroy. The old priests who then lived formed the connecting link with the terrible penal days. To the young priest coming then amongst them, they had many a gruesome tale of oppression to relate, but they had also many a proud and noble story to tell of the fidelity and sanctity and self-sacrifice of their predecessors and their people.

Canon O’Riordan described how many of the old priests had crossed the seas ‘in the small smuggling boat which, while it carried one brother or one cousin to join the Irish Brigade, not infrequently carried the other to return with his life in his hands to bring the consolations of religion to the old race at home, and to suffer and die as so many of them did, in the same good cause.’

He continued:

I remember an Irish-American priest who was born in the parish of Newmarket, adjoining mine, telling me that when a child he always accompanied on Sundays his grandfather over a mountain road to Mass. When they came to a certain point of the road the old man was accustomed to turn and face a rock on the mountainside and, removing his hat, to bow down before it. He was often wondering at this action of the old man and when he grew older, he asked him one Sunday morning why he did this. ‘Don’t be surprised my boy,’ said the old man, ‘that I revere that place. For twenty years of my life, kneeling on the heath, I attended Mass celebrated on that rock.’

Canon O’Riordan spoke of entering on ‘what seems a most hopeful period of our history’:

Those hostile to our race say we ought to forget those terrible days. The Irish Catholic who would forget those days is absolutely unworthy of the priceless heritage of the true faith transmitted to him … the simple heroism of our fathers, both priests and people, in those terrible penal days, will ever remain the brightest gem in the diadem of Erin.[10]

Cahirciveen born priest, Fr Timothy (Thade) O’Sullivan (1856-1934), who was a trusted friend of Parnell and whose sister was the wife of Kerry politician and author, Seán Ua Ceallaigh (John Joseph O’Kelly ‘Sceilg’), won a prize at Maynooth in the 1870s for his Solus Essay in Irish, ‘The Irish Priest in the Penal Times.[11] If this work could be unearthed in the archives of the college, it would be of great interest to modern-day scholars of the period.[12]

_____________________

[1] Transcript given in the Kerry News, 17 December 1913, signed ‘Your humble servant, Evans Vaughan, Dublin, 1650.’ [2] Historical Sketch of the Persecutions Suffered by the Catholics of Ireland under the Rule of Cromwell and the Puritans (1884) by Most Rev Patrick Francis Moran DD Archbishop of Sydney (p381). ‘The Rinuccini MS further attests that the father of this heroic martyr was the head of the sept of the Mac Moriartys whose hereditary possessions lay on the banks of the Mang in the county of Kerry’. An account of Father Thaddeus Moriarty, OP, last prior of the Dominican Convent in Tralee, is contained in Muckross Abbey A History (2018), pp285-287. [3] Kerry People, 15 February 1913. [4] Ibid. [5] Southern Star, 27 June 1931. Some years earlier, in March 1707, Captain Hedges, writing from Ross Castle, Killarney, advised that he had taken up one priest and signed warrants for six more, who he hoped would be in gaol in a few days. He had put all the Protestants under arms from Macroom to Killarney. The following year, 1 April, 1708, he reported that several Irish gentleman near this place had refused the Oath of Abjuration, and were prisoners at Tralee. They were Sir Nicholas Browne, ‘called Lord Kenmare,’ Colonel [Maurice] Hussey and his two sons, McCarthy More, and others. He urged that they should be removed to Ross Castle ‘as they could be supported there by their friends and not put the government to any great expense.’ In the same article above, a note about the building materials of Bantry House is given: ‘A respected parishioner of Kilmocomoge, a Gaelic speaker, a sterling Nationalist, and an interesting shanachie, writes: ‘When the French fleet arrived in Bantry Bay, Mr White rode his black mare to Cork in four hours through a path leading eastward through Shehy mountain. For his service he was raised to the peerage as Earl of Bantry. He or his successors built Bantry House with stones taken from the old Franciscan friary at Ardnambraher; and for the same purpose, he picked out the corner stones from what was left of Carriganass Castle. In my young days, I heard an old man telling the story of White’s destruction of the Abbey. He prophesied that the Whites would melt away like froth for laying their impious hands on God’s House; and that Franciscans one day would occupy White’s mansion and would place on it the old Abbey bell which lies buried in the strand, but was heard tolling in the penal days at Clashanaffrin (hollow of the Mass) in the mountain west of Keimaneigh, where the Holy Sacrifice used to be offered up in those dark and dismal times. When Father Crowley, the then pastor, heard of the arrival of the French sailors, he was celebrating Mass. He quenched the candles and cursed the invaders, whereupon there arose a terrible storm which prevented the landing of Wolfe Tone and the French troops. This story was told me by a person whose father was present at the Mass. Father Crowley, no doubt, having seen the sufferings of his flock during the penal days, did not want any more trouble for his parishioners’ (Southern Star, 27 June 1931). [6] The Irish Priests in Penal Times (1660-1760) by Rev William P Burke (1914), pp388-389. The late Fr Kieran O’Shea recorded same in his parish records of Castleisland. He noted that Father Charles Deorane was born in 1667, ordained in 1691 and in 1715 was acting in place of Charles Daly, deceased. [7] More on Fr Shanahan at this link: http://www.odonohoearchive.com/castleisland-the-early-roman-catholic-church/#_ftn3 [8] ‘In the Penal Days. An East Kerry Pastor’ by T M Donovan, Kerry News, 9 September 1935. See also Kerryman, 16 August 1941. A short story, ‘In the Penal Days When Priests were Educated in France’ was published in the Kerryman, 28 January 1933. It is worth noting here that T M Donovan was related to the Shanahan family, as shown in an anecdote made about his brother: ‘The old tomb of Fr Darby Shanahan is one of the oldest tombs in the St Stephen’s graveyard. Close beside this old tomb the remains of the late Rev John Donovan SJ,MA the defender of the Gospel of St John lies buried in his grandmother’s grave. This grandmother of the learned Jesuit Father, Mary Shanahan, was a niece of Fr Darby Shanahan. Had Father Donovan known that his remains would lie so near his 18th century kinsman, it would please him to think of his burial so near the tomb of the first parish priest of Castleisland.’ (‘In the Penal Days. An East Kerry Pastor’ by T M Donovan, Kerry News, 9 September 1935). [9] An account of his namesake, Fr Jeremiah O’Leary (1788-1866) who served Castleisland at this link http://www.odonohoearchive.com/castleisland-the-early-roman-catholic-church/ Right Rev Monsignor John O’Leary, who served under seven bishops, died at the Presbytery, Castleisland on 24 June 1918 at the age of 96 years, removing ‘one of the oldest, if not the oldest, priest not only in the diocese of Kerry but in Ireland.’ John O’Leary was born in Tralee in November 1821, educated at Maynooth, ordained at the age of 27 and spent 69 years in the ministry. His first and only curacy was Castletownbere, from there he took charge of Bere Island. He was afterwards parish priest of Dromod (Waterville), the united parishes of Ballymacelligott and Clogher (for nine years), and made Archdeacon of Castleisland after the death of Ven Archdeacon Irwin. Monsignor O’Leary was responsible for the erection of the spire on the parish church, he built a new parochial house, and was present at the consecration of the then bishop, Most Rev Dr O’Sullivan. He was a distinguished scholar and theologian and always remained aloof from politics, confining his energies to that of churchman. (Obituary, Irish Examiner, 27 June 1918.) [10] The Kerry People, 30 May 1903. Canon O’Riordan returned to the subject of Archdeacon O’Leary: ‘Fifty years ago the young Irish priest was brought into close contact with the noble and glorious traditions of those Penal days. The rural population were serfs on their own lands and were groaning under oppression. The priest was the one friend into whose ears they could pour their tale of misery and distress knowing that he would help them if he could … How often in those days had he to listen to the wild wail of the emigrants driven from their homes to what was then a distant and unknown land. Only the recording angel knows how often he prayed to God that He would stay the injustices inflicted on the people.’ Canon O’Riodan listed the services carried out by the archdeacon for the good of the community and asked ‘How many a hard journey through storm and rain often on the wild mountainside has he not made to bring the sacraments to the living and the dying.’ and continued: ‘When I consider the lives of priests like your venerable pastor in many districts in Ireland who are not moving among the homes of the wealthy nor enjoying the society of the cultured and the scholar, but who are living among the poor, working for the poor, in the school, in the pulpit, in the Confessional, on the altar, in their own homes, I am reminded of the Sermon ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.’ After the ceremonies, the nuns of the Presentation Convent provided a dinner during which an illuminated address, the work of Mr T Fitzpatrick, Upper O’Connell Street, Dublin was presented to the archdeacon by his parishioners, accompanied by a richly wrought silver tea service. The address was signed by Jeremiah Roche JP, Daniel O’Callaghan, Jeremiah Nolan, Maurice Murphy, Thos S Prendeville, Thos Kearney, T O’Connor, Brosna (Hon Treas), John P Rice MD, Patrick Broderick (Hon Sec). Archdeacon O’Leary replied to the Address, accepting the exquisitely designed testimonial that showed ‘striking evidence of the unfailing love and large-hearted generosity lavished on me by the people of Castleisland since I came among them.’ The party proceeded to the Presentation Convent schools after the meal where a Jubilee Chorus by Mother De Sales to music by Arthur O’Leary was rendered, and another illuminated address, the work of Mr O’Reilly, Westmoreland-street, Dublin together with a silver tray, was presented to the archdeacon by the teachers. An address from the children of the Presentation School was also read, and another from the Sodality of the Children of Mary, Castleisland. Mr Buckley of the Castleisland Gaelic League also delivered an Address in Irish. [11] The prize was won earlier by Very Rev Daniel O’Keeffe (1849-1895), parish priest of Killarney, a native of Cuillan, Co Cork who was regarded as the best Irish scholar at Maynooth in his day. Fr O’Keeffe was ordained in 1873, and appointed to Killarney in 1889. His early death caused widespread upset, ‘the crowd of poor who surrounded the hearse mourned more deeply his loss. One old tottering woman of seventy clutched one of the hearse pillars and spoke broken words of thanks to the coffin. Another poor old man, lame and blind, hobbled alongst the hearse side on his crutches. He had lost a friend from whom he ever received kindness and sympathy’ (Kerry News, 20 September 1895). Very Rev Canon Michael Hamilton (b1894), parish priest of Newmarket-on-Fergus, Co Clare, won the Solus Prize, the most coveted award in the seminary, three times in three languages, Irish, French and English. A Mass in the Mountains and Poems (1881) by S M is ‘A brief tale dealing with the days of persecution that followed the violation of the Treaty of Limerick … a vivid glimpse of the vicissitudes which well-to-do Catholic families encountered and the dangers which pastors and their flocks ran when the administrators of the penal code made their chief effort to root out Catholicism in Ireland’ (Dublin Weekly Nation, 13 August 1881). The Penal Mass and Other Poems by Canon Cunningham, parish priest of Templederry, with an introduction by Rev Joseph Darlington SJ was published in 1930. [12] Father Timothy (Tadhg) Ó Suilleabháin (1856-1934) otherwise Fr Timothy O’Sullivan, son of Patrick O’Sullivan (died 1908) and Catherine O’Kelly, was born at Lisbawn (Lisbane) Caherciveen on 17 May 1856. He was educated at St Brendan’s Killarney and at Maynooth College, which he entered in 1875. While studying there he won the Solus for an essay in Irish on ‘The Irish Priest in the Penal Times.’ He was ordained in 1883, and went to England where he served the Archdiocese of Westminster. His first appointment was as assistant priest of the Hounslow and Sunbury Roman Catholic Mission. In 1884, Hounslow was created a distinct Mission and he was placed in sole charge there as RC priest of the Church of Saints Michael and Martin where he remained for twenty-one years building there, in 1885, a school/chapel at 94 Bath Road. He was chaplain to the military forces there until the end of 1904. He was appointed to the Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel at Harwich (built in 1869, since demolished) in 1905 (where he kept a fine library almost destroyed in a fire). In 1914, it was reported that ‘Rev T O’Sullivan, who was for so long a period Catholic Priest at Hounslow, and one of the most active and popular public men of the district, has been appointed a chaplain to the British troops at the Front and will shortly proceed to France to take up his duties. When the worthy priest left Hounslow about nine years ago, his health was greatly impaired by overwork and anxiety and although he battled manfully against his weakness, and filled various appointments, he was at last compelled to go into Retreat at Twyford Abbey for rest and treatment. The fact that he has been accepted for active war service implies that he has entirely recovered his health and his many friends in this neighbourhood will rejoice at this’ (Middlesex Chronicle, 19 December 1914). His last mission was at Hoddesdon where he remained until about 1928 when ill health caused his retirement (in October 1999, the funeral of former child star Lena Zavaroni, 35, was held at St Augustus RC Church in Hoddesdon where she had lived for several years). Fr Thade O’Sullivan died in Dublin on 6 August 1934, ‘It was consoling to see at his graveside in Glasnevin the Venerable Archdeacon Casey of Castleisland who, as a young curate in Caherciveen, walked with him as far as Carhan Bridge before taking ‘the long car’ the day he first left for London. Had he been buried in the grounds of the O’Connell Memorial Church, as was long the intention, Kerry would have given him a funeral memorable as that of his kinsman, Father Eoghan’ (Obituary, Kerry Reporter, 22 September 1934).