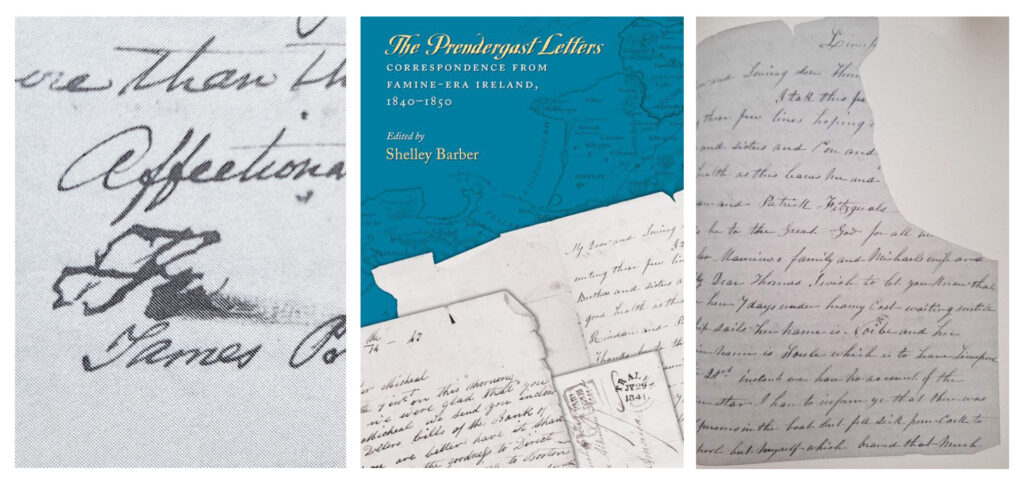

An almost unique opportunity to study the raw material for judging both the lives of a family in Ireland during the famine years and the lives of the emigrant children in America – Ruth-Ann M Harris, Historian, Boston College

During the period 1840 to 1850, James Prendergast and his wife Elizabeth (née Hurley) of Bleach Road, Milltown, Co Kerry, parents of six children, corresponded regularly with three of their offspring in Boston, who had emigrated there in succession. The letters survived, and in recent times, were transcribed, edited and published.[1]

Musician, artist and author Thomas O’Sullivan of Beaufort, who contributed to the book and attended its launch in Boston, has kindly donated a copy to Castleisland District Heritage.[2]

When do ye intend coming to the native isle as we are always impatient to know

The principal author of the correspondence, James Prendergast, employed his neighbour as amanuensis.[3] It is a one-way correspondence for there is no evidence that the replies to James’s letters survive. James continues as principal author until his death in 1848, after which the correspondence is continued by his widow Elizabeth. The letters end with Elizabeth’s emigration to Boston in 1850 at the age of about eighty.

Let us know in your next letter when do ye intend coming home

In content, the letters are full of family and community news, and enthusiastic enquiry about friends or acquaintances in America. In one letter alone dated 20 April 1842, the names mentioned are Quirk, Riordan, Donoghue, Lynch, Sullivan, Fleming, Mahony, Connell, Moynihan, Buckley and Kerrisk.

Health is of the greatest consideration in the entire correspondence and the anguish of James and Elizabeth for the wellbeing of their offspring is communicated from letter to letter.

There is constant reference to missing letters and discussion about the reliability of the post. James frequently writes about ‘the fraud in our home post. I strongly suspect it is for the lucre of the shilling they delay the letters.’[4]

News of deaths in the locality is frequently given. James mentions the death of Rev John Quill in 1842, former parish priest of Milltown, remarking on ‘the magnificent procession at his funeral to Milltown.’[5] Elsewhere he mentions the death of John Thomas Eager and that ‘Rathpogue is now in the hands of the Godfrey family.’ ‘Let Mrs McKenna know that her father Roger Sheehy is dead these two months past,’ he advises in another letter, and laments that ‘young Patrick Heffernan of Rathpogue died within a few hours sail of Quebec,’ adding that ‘Mary Connor, sister to Jerry Connor late of Milltown who was going to her brothers in Hamilton I heard died after landing.’[6]

The state trials is still in the Lords … all other news is disregarded here (July, 1844)

In the early 1840s, discussion about O’Connell and repeal dominates. James informs his children, ‘Repeal is carrying on in great splendour by our Liberator, Daniel O’Connell, we are all in this country repealers.’[7] James conveys news of Daniel O’Connell’s arrest and trial in Dublin to Boston:

The Liberator was on trial in Dublin this time past for treason against the government for holding repeal meetings for enticing the people at those meetings and for introducing arbitration courts in Ireland and also for collecting money at home and from foreign lands called America they say for the dismemberment of the Empire but, they are liers. Daniel means no such thing. He means equal laws equal justice and equal right to Ireland together with some means of support for the poor of all Ireland. He has beaten them upon their causes.[8]

Inevitably, as the decade progresses towards famine, the mood of the correspondence changes, with echoes of The Diary of Robert O’Kelly.[9] James first mentions that ‘a disease has seized the potato crop’ in October 1845, and in November the following year, he writes, ‘The state of this country is almost beyond description.’[10] By the summer of 1847, James tells his children, ‘Our hope is in God.’[11] One year on, ‘people were doing crime to get something to eat or to be transported, preferring it to be a better life.’[12]

Your brother Michael has buried two children, Mary and James (October 1843)

The recipients of the correspondence were the three youngest children of James and Elizabeth’s six children, only daughter Julia (Mrs Cornelius Riordan) and sons Jeffrey and Thomas. The letters make regular reference to Julia’s brother-in-law, Daniel Riordan, who was employed at the Victoria Hotel in Killarney. Of this employment James confides, ‘Daniel Riordan is still at Finn’s Hotel in Killarney. He has plenty to eat and drink but got only 15s last season and no promise of wages this season.’[13]

John, Maurice and Michael remained at home, and seem to have worked for the Eager (Agar) and Spring families at varying intervals.[14] John had a position with Charles Agar but left after Charles died, which left him and his family in ‘low circumstances.’[15] He was living in Tralee in 1844. John died in 1847, and by 1850, his eight-year-old daughter Elizabeth was orphaned.[16] Maurice wrote to his brothers in December 1847, ‘I assure you I don’t forget him, the thought of him often gives me a lonely feel.’[17]

Maurice, who lived at Ardagh, Dromin and Ballyoughtra, worked for Richard Eager until 1841, and hoped to work for another member of that family at Curraglass, Glenflesk. One of the letters bearing date 11 October 1842 carries the news that attorney Richard Eager Esq had died.

At some point Michael and his family moved next door to his parents. The family was often in poor circumstances. In May 1844, four of Michael’s sheep were killed and stolen from his field. As James informed the family in America, ‘The heads and trotters he found after the night in the field with young lambs in them. I say that he would be capable of pulling out were not for that occurrence.’[18]

Michael was anxious to join his siblings but was encouraged by his father to remain at home until 1847, when he left on 27 March of that year. His wife Ellen and their four children remained behind. In December 1847, Ellen, destitute but for family support, wrote: ‘The children are bare and naked from cloaths.’[19]

The hand-to-mouth existence of the Prendergast family, and the countless others in Ireland, is starkly illustrated in the letters. ‘I feared I would have died before your relief would reach me,’ writes James to his children in 1848, ‘and I would be a burthen on the parish for my funeral.’[20]

Nothing is so precious as health as without it, the wealth of the world can scarcely yield comfort

James and Elizabeth were immensely proud of their children’s conduct in America, particularly in responding to repeated requests from concerned families in the locality hoping to hear news of their loved ones, or asking for help to find employment for members of their families who wished to take their chances overseas. Their continued assistance of others caused James to write: ‘Ye are the best children that left this country for the last 100 years. Those who never saw ye or knew ye are thankful to ye and pray for ye in consequence of the kindness ye have shewn.’[21]

The praise was not without merit for it is very clear that the family in Boston kept their family back home alive. The money they continually sent was a lifeline. Maurice and his family were saved from death in 1847, ‘They may thank ye for their lives … what ye sent was a principal means to recover them.’[22] James repeated the thanks in August, ‘They can never return ye thanks. It was what ye sent your mother and me that kept them alive.’[23] Maurice, once recovered, was able to thank his siblings himself: ‘The last three pounds was a total means of recovering me an my family.’[24]

On 15 December 1848, James Prendergast wrote his last letter to his children:

The last six weeks I am confined to my bed … I cannot expect to hold out long. The only regret is that of leaving your mother alone … I am pennyless … there is not a shilling in the house to defray my funeral expenses … Maurice is writing this, he attends me in raising and laying me on my bed. I attempted to write my name and tho’ I was supported by Maurice and your mother I was unable to.

James passed away three days later, on 18 December 1848. He was interred in Keel cemetery alongside his son John. Elizabeth, his widow, wrote to her children in Boston, ‘Not a farmer in the parishes here was attended to the grave with greater respect.’[25]

Elizabeth Prendergast departed Milltown for Boston with her eight-year-old granddaughter and namesake, Elizabeth, the orphaned child of her son John, in the summer of 1850. She was to be reunited once again with her daughter and sons and their families. She died there on 15 March 1857 aged 87 and was buried in Cambridge Catholic Cemetery on St Patrick’s Day. The fate of her granddaughter is not known.

Genealogy of the Prendergast family in America by Marie E Daly, Director of The Research Library, New England Historic Genealogical Society, with some photographs, occupies pages 171-190 of The Prendergast Letters. It shows that Maurice and his family may also have gone to Boston.

Two of Jeffrey’s children, James Maurice Prendergast and Julia Catherine Prendergast, were patrons of Boston College. James Maurice contributed to the first building on the Chestnut Hill Campus in 1909, and his sister donated money to Boston College Library in the 1930s to help purchase the Seymour Adelman Francis Thompson Collection in memory of her brother.

In all likelihood, they were the donors of the letters.

__________________________

[1] The Prendergast Letters are held in John J Burns Library, Boston College. The Prendergast Letters Correspondence from Famine-Era Ireland, 1840-1850 edited by Shelley Barber was published in 2006, in which it is observed that ‘The letters demonstrate the importance of such communication during this period of mass emigration. Over a hundred individuals, other than immediate family members, are named in the correspondence. The letters ask for and offer information about neighbors on both sides of the Atlantic. They convey details of weather, crops, local economy, and banking and postal services. The politics of the day, including the proposed Repeal of the Act of Union and the trial of Daniel O’Connell, are mentioned. There are accounts of illness, births, and deaths. Family members in Ireland acknowledged the receipt from Boston of over £139 in monetary assistance. It is clear that this money was the means of preserving the family. The letters are most notable for the descriptions they contain of the potato blight, subsequent years of famine and hardship, and the response of the family, community, and nation to these extraordinary circumstances. The letters provide insight into the life they left behind, the parents and traditions that gave them a solid foundation and skills which allowed them to succeed in the face of adversity’ (pp1 & 18). [2] Thomas O’Sullivan contributed a map which appears on pages 10 and 11 of The Prendergast Letters Correspondence from Famine-Era Ireland, 1840-1850 (2006) Edited by Shelley Barber. Thomas, founder of the World Bodhrán Championships in 2005, has also contributed a copy of his recent composition, ‘Jarvey Song.’ Thomas has contributed a typed copy of the Prendergast letters held in IE CDH 215. [3] James had some literacy skills but as he explained in a letter dated 1845, ‘Our scrivener or writer Patt Mahoney is as free to us as if one of yourselves were at home. Therefore do not neglect writing to us often, as it is my chief object’ (The Prendergast Letters Correspondence from Famine-Era Ireland, 1840-1850 (2006) Edited by Shelley Barber, p85). [4] The Prendergast Letters Correspondence from Famine-Era Ireland, 1840-1850 (2006) Edited by Shelley Barber, p48. [5] Ibid, pp43-44. [6] Ibid, pp65, 67, 110-111. [7] Ibid, p54. [8] Ibid, p63, December 1843. [9] Robert O’Kelly was born in Castleisland in 1835 and left a memoir for his children and grandchildren. https://www.odonohoearchive.com/the-diary-of-robert-okelly/ [10] Ibid, pp94 & 99. [11] Ibid, p106. [12] Ibid, p135-136. [13] Ibid, p69. Daniel remained in this employment for many years but by 1850, he was working at the Kenmare Arms Hotel, Killarney. [14] News of the Spring and Eager families features with some prominence. A portrait of Francis Spring (1780-1868), land agent for the Godfreys, is on p51. A portrait of Fr Batt O’Connor (1798-1890) also appears on p52. Fr O’Connor is discussed in the letters. [15] The Prendergast Letters Correspondence from Famine-Era Ireland, 1840-1850 (2006) Edited by Shelley Barber, p67. [16] Ibid, p18. The correspondence mentions a daughter of John’s named Julia (Jude) but it would seem that only Elizabeth survived. James writes in 1847, ‘I need say nothing to you about John’s death. Michael can tell you every thing. I went to his wife and asked if she would suffer her child to go to America. She said she would let her come to myself but would be unfond to let he go to America however that she would consider for some. I released some frocks of hers that were pawned and I intend bringing her. She is a fine child and much like her father in her way. I must always have an eye to her. She is the only one now living that was called after your mother Elizabeth’ (Prendergast Letters, pp102-103). The date of death of John’s wife is not known but had occurred by the time Elizabeth Prendergast took her granddaughter to Boston in 1850. [17] Ibid, p124. [18] Ibid, p67. [19] Ibid, p119. The family eventually joined Michael in the early 1850s. [20] Ibid,p130. [21] Ibid, p115 James to his children in 1847. [22] Ibid, p107, James to his children 25 July 1847. [23] Ibid, p110. [24] Ibid, p124, December 1847, [25] Ibid, p147.