In the ‘Castle of the Island’ in the year 1422, an indenture was drawn up between James, Earl of Desmond, and Fitzmaurice, Lord of Kerry and Lixnaw. The document, witnessed and sealed by the Bishop of Ardfert, reveals how two powerful families engaged in a treaty for peace.

Indenture of Agreement between the Earl of Desmond and Patrick Fitzmaurice of Lixnaw, 1422

This indenture, made at Castleisland the next March following the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin in the IX year of King Henry V, 1422, Lord James Fitzgerald, Earl of Desmond, Lord of the Liberties of Kerry, and Patrick Fitzmaurice Fitzthomas, Captain of his Nation, of the other part witnesseth that the aforesaid Earl and Patrick are agreed, and at peace, in form of this treaty, in respect of all strifes, bad and moved between them up to the date of these presenting.1

All this however, did not prevent the Fitzmaurices from kicking against the goad of the all powerful Earl of Desmond and their kinsmen and neighbours, as we see in the Battle of Lixnaw.2

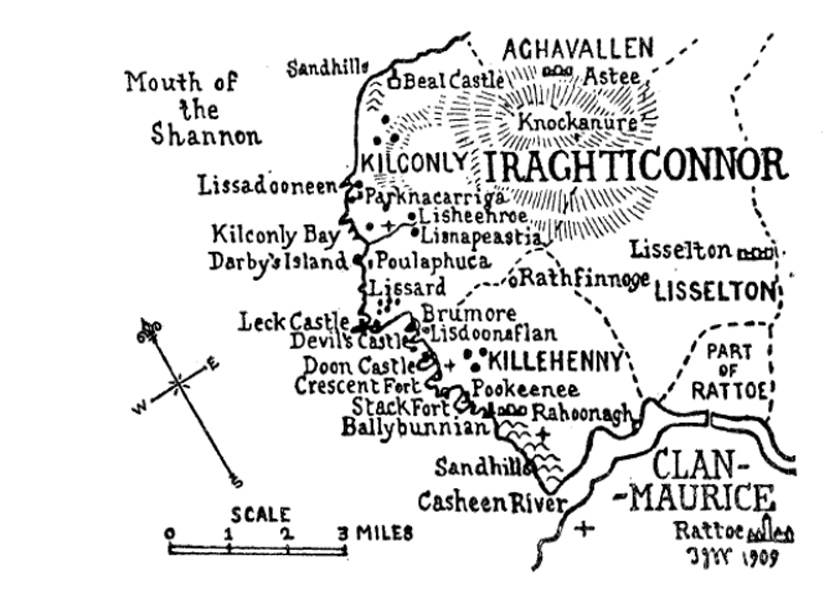

This battle was fought at Lixnaw and Ballynageragh in 1568 whilst Gerald, Earl of Desmond, and his brother, Sir John Desmond, were undergoing captivity in the Tower of London. At this time, James, son of Maurice Dubh, Mac-an-Earla, assumed the Palatine power ‘and preyed and plundered, wasted and burned the lands of Fitzmaurice to the very gates of Lixnaw.’

James attacked Lord Kerry’s Court on the western side while he sent O’Connor Kerry with the Clan-Sheehy and their predatory forces to the eastern side of the town so that the Lord of Lixnaw and his forces were thus surrounded on every side.

Edmond MacSweeny, son of Gilla-Duv, son of Donough, son of Donnell-na-madhman (Donald of the Victories) was constable or leader of the troops of Fitzmaurice and though he had scarcely fifty galloglasses or fighting men under him, he did not think it honourable to desert the Lord of Lixnaw in this great danger.

Let us attack at once

Fitzmaurice dreaded to attack such a large party of well armed men but MacSweeny bravely cried out: ‘Let us attack at once the Clan-Sheehy for against them our indignation is greatest.’ The Clan-Sheehy on their side was delighted to see Fitzmaurice’s party approach for they felt confident that so small a number could be easily overcome.

They were, however, mistaken.

MacSweeny and his galloglasses, assisted by Captain O’Malley and his marines, made such a brave attack on the MacSheehys and the Geraldine forces that they were completely routed and a great number of the Geraldines and the MacSheehys were killed. There fell Edmund, son of Edmund MacSheehy, Chief Constable of Desmond, ‘a wealthy and affluent man’ say the Four Masters, famed for his dexterity of hand and house of hospitality.3 Murrogh Balb, son of Manus MacSheehy; Teig Roe O’Callaghan, son of O’Dwyer, son of the White Knight; Faltagh (Wall) of Dun Moilin (Dunmoylan Castle); John, son of Gerald FitzGerald, heir of Lickbevune Castle.4

Also slain was John O’Connor Kerry, otherwise ‘John of the Battles’.5 Another John, son of Garret Fitzgerald, was taken prisoner, and many others were either killed or made hostages during this battle.

After the Battle

The battle was fought, but conflict was ongoing, as seen in the following letter of Thomas, 16th Lord of Lixnaw, who wrote to the Lord Deputy, Sir Henry Sydney some years later complaining of the harassing wrongs inflicted on him and his tenants by the Lord Palatinate:

My bounden duty premised to your good lordship advertising your lordship that the 12th of ths present month certayne of the Erle of Desmond’s men, in several companies, came to my poore country. One companie to the south side of the country and one to the north side, and from one of my tenants (being my chaplain being about the edge of four score years) tooke awaie his plough garrens, killed two of my men, and left not so much as my poore greyhounds unkilled, so that the man’s guts from the dogges could sears be discerned; and the same night another companie came to one of my horsemen in the north side of my countrie and tooke from him 15 stoode (stud) mares, and drowned three, and the next night after, being the 24th of this month, another companie of the M’Aghe M’Tirrelaghe, with the Erle’s Constable of Carrig-an-Foyle, came to another of my poore tenants, being the best I hadde, and from him tooke awaie his plough to his utter undoing; all this being done the first or second night after his lordship coming to Kerry, and as I am informed by his lordship’s procurement. The which I humbly beseech your honor to consider and being not therewith contented, but swares and says that he will with all his power come to invade my country, praieing your honour (if there be anie remedie) to see through my afflicted case remedied, being one always ready to answer to onie right and lawrie before your honor and thus I humbly take my leave committing your honour to the keeping of God, from Lixnawe, the 25th of August 1576. Your Lordship’s alwaies to command. Thomas Lixnawe.

He complained again that on September 1st, the earl took 2,100 kyne (cattle) and 200 copuls (horses) besides 600 kyne and 800 sheep already lifted.

The Four Masters relate another raid in 1578 as follows:

A contention arose between the Earl of Desmond, ie, Gerald, the son of James, the son of John, and Fitzmaurice of Kerry, namely, Thomas, son of Edmond, son of Thomas, and the earl took Bally-mic-an-chaim Castle from Fitzmaurice.

The young Abbot O’Torna (or O’Dorney) having joined the earl, was killed at the castle door of Lixnaw by a ball shot after the earl had entered the castle; and had there been no other evil done than the killing of this abbot, it would have been great enough. A great number of Fitzmaurice’s people were killed and drowned the same day.

They continued for some time thus at war with each other until at last they made peace and Ballymacaquim was restored to Fitzmaurice together with his hostages and a countless number of herds of kine and horses.6

Demise of the Lords of Lixnaw

It does seem strange, observed a nineteenth century writer, that the long descended family of Fitzmaurice of Lixnaw, dating in Kerry from the English Conquest, should not now have a trace or memorial in the county from which it took title except the empty modern monument at East Clogher and the ruined chapel adjoining the cathedral at Ardfert.7

The ‘empty modern monument’, a mortuary chapel to Thomas, 21st Lord Kerry and 1st Earl of Kerry, was in such condition because tradition held that the lead coffin was utilised for bullets in the rebellion of 1798.

It would seem that Lord Kerry built the chapel at Kilbinnaun, site of an ancient church, at some period before his demise in 1741.8

In the centuries that followed, it remained a symbolic landmark of the Lords Kerry, the first of whom died in 1280, and the last in 1818.

In 1934, a writer observed that ‘the shadow of ruin’ was creeping around the old monument of Lixnaw. ‘Up to a few years ago,’ he continued, ‘money came from some source for its annual repair but the trustees must have died or its appropriated funds exhausted for no one no longer seems to care about it’.9

The writer acknowledged that it was a sacred, if not historic, place and predicted its ruin: ‘In five years from now, grass and weeds will mark the place where it stood.’

It was demolished in 1957:

The total area of the hill was about 14 acres and its summit rose 70 feet over the level of the surrounding land. The monument itself was an imposing edifice and no doubt reflected credit on the architects and stone masons of the bygone days. The tower, 40 feet high, had a circumference of 100 feet being circular in shape with walls four feet thick. The tomb, also circular in shape, was a spacious one, being about 15 feet in diameter and having a flat stone roof. As the tomb lay directly under the tower, this roof also comprised the tower’s floor and down through the years sustained the weight of many herds of cattle.10

Fitzmaurice, Lords of Lixnaw by Senectus

The following account of the Lords of Kerry and Lixnaw was published anonymously in 1865 in an effort to rescue the history of the family from oblivion.11

For more than six hundred years the Lords of Lixnaw (in Irish, Leac Snamha) distinguished themselves as much for their indomitable courage and love of chivalry as for their princely munificence and boundless hospitality. In its day, the old Court of Lixnaw was a fountain of charity from which freely flowed the milk of human kindness.

The walls of the old house, and only the walls, are still extant and though they are broken and crumbling now, one can gather from them a ray of past glories, of fallen greatness and faded grandeur. Just at its base flows the old river Brick where many a time the young lords beguiled the hours away in capturing the salmon which abounded there. In those days the country around must have been very wild and wet as it was in a great part boggy land.

In early times the sept was always faithful to the English Crown with the exception of the fourth Lord Kerry. They were mostly of a religious temperament, advancing the interests of the Catholic Church.

Religious houses were erected by them in many places of which nothing is known and which it escaped even the diligence of Smith in his history. At Lerrig, near Ardfert, a religious house of some kind was built but not a stone stands there now to mark the place. Some persons attribute the founder to one of the Lords of Kerry. Indeed the 3rd Lord Kerry must have been a nobleman of a very pious disposition for he built the Leper or Lazar House at Ardfert, now thrown down and the stones used for other purposes.

There are many stories told of the Lords Kerry. One of the Barons of Lixnaw is said to have killed his servant in a fit of rage and to atone for it, had a shrine erected in Kiltomy churchyard dedicated to St John the Evangelist. A stone from Rome was laid on the shrine which was said to possess powers against epilepsy. To this place the Lord Kerry went every morning to pray in the manner of Henry, the royal murderer, at the tomb of Thomas A Becket.

Another strange tale is told of Hanora, wife of the 19th Lord Kerry, whose mysterious death in the presence of an archdeacon caused the people to believe in his superhuman powers. Her remains became a gruesome curiosity in the locality.

Another Lady Kerry suffered a strange death after dining at Beal Castle with Maurice Stack in 1600. The occasion ended with Stack being hurled to his death from a window into the courtyard. Lady Kerry died about a year later.

Origins of the House of Lixnaw

If we come at once to the root of this ancient family tree we must turn to the shores of Italy where flourished Otho, a baron of the land and a descendant of the Duke of Tuscany. This Otho was father of Walter, who came into England with William the Conqueror in 1066 and was made a baron and constable of Windsor by that monarch for his services against Harold at Hastings.

This Walter married Gladys, daughter of Ryall-ap-Coyn, by whom he had issue three sons, Gerald, Robert and William. Gerald, who was, according to the custom of the time, surnamed Fitzwalter, had from Henry I a grant of Molesford, County Berks, and married in 1108 Nesta, daughter of Resap-Griffith, prince of South Wales, who had it is said been previously the leman of Henry I. This Nesta was by Henry, the mother of De Marisco, Constable of Cardigan, and the celebrated Robert Fitzstephen, the first English invader of Ireland in 1169.

Gerald had issue by her three sons, William, Maurice and David. William was the ancestor of the Lixnaw family, Maurice of the Ducal House of Leinster while David was consecrated bishop of St Davids in 1147.

William, who was married to Catherine, daughter of Sir Adam De Kingsley of Cheshire, was sent over to Ireland by Strongbow with his eldest son, the celebrated Raymond Le Gros, in 1171, and assisted materially in the advancement of the Norman interest. But shortly after returning to England, he died there in 1173.

Raymond remained in Ireland and soon after married Baselia, sister of Earl Strongbow, and had as a marriage portion with her a large temporal grant and the constableship of Leinster. Some time afterwards McCarthy, King of Cork, solicited Raymond’s assistance against the attacks of his rebellious son, Cormac O’Lehanagh, and after subduing him, received from McCarthy for his valuable services a large tract of land in Kerry where he settled his eldest son Maurice Fitzraymond.

Maurice espoused the daughter of Miles Fitzhenry, founder of Connell (or Connal) Abbey, Kildare, and Chief Governor of Ireland, with whom he got the lands of Rathivoe (Rattoo), Killury and Ballyheigue in Clanmaurice as a marriage portion. By this lady he had Thomas and Gerald.

The twenty-three Lords of Kerry and Lixnaw

Thomas, Justiciary of Ireland, who first assumed the surname of Fitzmaurice (that is, son of Maurice) became 1st Lord of Kerry and Lixnaw. From him the barony of Clanmaurice takes its name.

His brother Gerald was ancestor to the family of Liscahane and Kilfenura called the tanistry or second house, which was attainted in Elizabeth’s reign and whose heiress general, Ellice, was mother of Conor O’Connor of Carrigafoyle. He was married secondly to Catherine, daughter of Milo de Cogan and had by her a son William from whom sprung the families of Fitzmaurice of Brees in Mayo and of Ballykealy in Clanmaurice, anciently barons thereof.

Thomas, 1st Lord Kerry, had in his youth a grant of ten knights fees in Kerry from King John in the first year of his reign and an ancient rent of 4d by the acre was reserved to the family for a length of time from Bealtra to Crahane (probably Carahane).

He married Grace, daughter of McMorrough Cavenagh (or Kavanagh) and granddaughter of Desmond, the detested King of Leinster, and founded the Grey Friary of Ardfert in 1253.

At his death in 1280, he was buried on the north side of the great altar of the Grey Friary of Ardfert, which he had built. He died it is said at the house of his son-in-law, Sir Otho de Lacy, in Browry (perhaps Bruree in Limerick) on the feast of Saints Peter and Paul.

He had two sons, Maurice and Pierce and two daughters.

Pierce became ancestor to the families of Meenogahane, Ballymacaquim and Croshnishane in Clanmaurice. The greater part of a huge castle or keep still rears its head over the quiet plains of Ballymacaquim and is now used by the farmers who hold the land around it for various purposes of utility.

Maurice, the eldest son, 2nd Lord Kerry, married Mary, daughter and heiress of John McElligott of Galey in Clanmaurice (not McLeod of Galway as some writers say) by which alliance, the family obtained from Richard I an inheritance of five knights’ fees in Coshmany and Molahiffe in Desmond.

This Maurice sat in the Irish Parliament in 1295 and attended a writ of Ed I in 1297 after which he proceeded on an expedition against Scotland; Wallace the deathless being about that time at the head of his faithful men of Lanark against English domination. He died in Lixnaw in 1303 (or 1305) and was buried with his father in Ardfert.

He was succeeded by his eldest son Nicholas Fitzmaurice, 3rd Lord Kerry. He received the honour of knighthood at Adare from John, Lord Offaley, for assisting him to suppress the rebellion of the Irish in Munster and in the same year, 1312, he also went against the Scots. He must have been a nobleman of a very pious disposition as he made several grants of land for religious purposes, built the Leper or Lazar House at Ardfert and the old bridge at Lixnaw.12

He also built the castles of Portrinarde and Ardfert.13

He married Slany, daughter of Connor O’Brien, Prince of Thomond. He died in 1324 leaving three sons and six daughters.

He arranged the marriage of one of his daughters, Elinor, to Maurice, the 1st Earl of Desmond, and gave as a marriage portion with her the lands of Killury and Ballyheigue and ‘the Island of Kerry and the whole seigniory thereto’.14

Another daughter, Margaret, married Donald MacCarthy More, Prince of Desmond. Maurice and John, the two eldest of his sons, were successive lords of Kerry and were not, at least the former, very lucky in their fortunes.

Maurice Fitznicholas Fitzmaurice, 4th Lord Kerry, had a dispute with Dermod Oge McCarthy and killed him on the bench before the Judge of Assizes in Tralee in 1325. He was tried and attainted by the parliament at Dublin but was not put to death. His property was confiscated on account of this outrage and fourteen years later, 1339, he revolted against the English government and otherwise raised disturbance.

He was ultimately taken prisoner by Maurice, Earl of Desmond, who slew nearly 1500 of the then rebels. Maurice Fitzmaurice died that year, his death being accelerated, it is said, by the scantiness of his diet during his imprisonment. He was interred at Ardfert.15

Having no issue, his brother John succeeded him in honours as 5th Lord Kerry and enjoyed them but nine years for he died in 1348 and was succeeded by his son Maurice.

Maurice Fitzmaurice, the 6th lord of Kerry, fighting for Edward III against the Irish in 1370, was taken prisoner on the 6th of July in that year with Lord Thomas Fitzjohn and several other men of note. Maurice was a Lord of Parliament in the 48th of Edward III and departed this life in 1398 at Lixnaw.

His eldest son, John, dying before himself, he was succeeded in the family honours by his second son, Sir Patrick, by some called Barbatus (bearded) as 7th Lord of Kerry. James, the 7th Earl of Desmond, having obtained the custody of the counties of Kerry, Cork &c, entered into a deed as lord of the liberties of Kerry with Patrick, Lord Kerry, styled then Patrick Fitzmaurice Fitzjohn, Captain or Head of his Nation, whereby the said Patrick was bound to answer to the earl and his heirs at his assizes to which agreement William Stack, Archdeacon of Ardfert, and Nicholas, Bishop of that See, were witnesses.

Patrick was married to Catherine, daughter of Teige MacCarthy More. Patrick is recorded as having been killed in Clare in 1410.16 He was succeeded by his eldest son Thomas as 8th lord while his second son Nicholas became Bishop of Ardfert in 1420.

Thomas died in 1469 and was represented by his second son Edmond as 9th Lord Kerry. In 1485 Edmund appeared in the Court Palatinate of Dingle before a Mr Coppinger and there recovered lands which had been granted to his ancestors by King John but which were taken from, we believe, Maurice, 4th Lord Kerry some 146 years before.

This nobleman died at Lixnaw in 1498 when the title devolved on his eldest son, Edmond, as 10th Lord Kerry who, after the death of his wife, became a lay-brother in the Grey Friary of Ardfert. He took little or no part in mundane affairs at any period of his life, his spirit dwelling in a loftier sphere.

His son Edmond was now 11th Lord Kerry but of him we can record nothing save he led a quiet secluded life, never caring to go beyond the pale of his own hillside keep. He was created Baron of Odorney and Viscount of Kilmaule by Henry VIII in 1537 which title became extinct on his death, without male issue, in 1541.

He was succeeded by his brother Patrick as the 12th Lord of Kerry. He married, by dispensation from the Pope, Slany, daughter of Murrough, the 1st Earl of Thomond and 1st Baron of Inchiquin and had issue but Patrick, Lord Kerry, died young, from a cold caught while hunting at Drumleggagh in the year 1547.

It is worth remarking that Patrick’s widow Slany remarried Sir Donald O’Brien of Duagh, second son of Connor, Prince of Thomond. The couple had three sons and three daughters, Turlogh, Mortogh, Connor, Mary, Sarah (who married O’Sullivan Beara) and Penelope, who married as her first husband (and his third wife) the 16th Lord Kerry.

Patrick left two sons minors, Thomas and Edmond (or Edward), who became successively lords each in his turn. Thomas, 13th Lord Kerry, being a minor, was placed under the guardianship of his grandfather James, the 15th Earl of Desmond, and continued so until his death at the Castle of Listowel in 1549, a little more or less than a year after he had attained his majority.

The title and honours devolved on his brother Edmond (or Edward), 14th Lord, who was also under the guardianship of the Earl of Desmond. In two short months after his brother’s death, while at the castle of Beaulieu (Beal), he too died.

The estates and honours reverted to his uncle, Gerald Rua (the red-haired), third son of Edmond, the 10th lord, who became 15th Lord Fitzmaurice of Kerry but he too, one month later, as if some unknown power was warring against his race, was called away with startling suddenness. He was killed in Desmond, whether by accident or design or how we are unable from the records to say. He had been married not more than a month to Julia, daughter of Cormac Oge McCarthy, Lord Muskerry. He was interred in the family vault at Ardfert on 1st August 1550.

In less than one year, three distinguished nobles of this house had been hurried into eternity.

Gerald’s brother, Thomas, who was born in 1502, succeeded to the dignity and estates at 16th Lord of Kerry. He served in the Milanese as an officer under the German emperors before the honours accrued to him. And being in Milan at that time, Gerald Fitzmaurice, the next male heir presumptive, took possession of Lixnaw.

Gerald held Lixnaw for about a year when an old woman named Joan Harmon, who had been a nurse to Thomas, 16th Lord, set out in her old age to Italy with all the vigour and earnestness of youth, accompanied by her daughter. At Dingle she boarded a small vessel then in the harbour bound for France from where she proceeded to Italy and Milan where she sought Lord Thomas. She told him of Gerald’s actions but she died on her return voyage to Ireland.

Lord Thomas however reached Ireland safely but Gerald would by no means give him the estates and so disputes and quarrels grew between them for two years or more until Gerald finally surrendered to Thomas. In a deed made to Thomas by John FitzRichard, 5 Edward VI, he is designated Lord of Kerry and Captain of his Nation.

In the first year of King Philip and Queen Mary, Thomas received a letter from their majesties dated at Hampton Court, the 23rd September and directed to ‘their trusty and well-loved subject the Baron of Kierry’ informing him of their marriage and requiring him to assist the Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam to redress those disorders which had crept into the State since the death of Henry VIII, both in matters of religion and to preserve the kingdom in peace, tranquility, justice and honour.

Also, by a patent dated by the queen at Westminster on the 23rd of October following, in consideration of his good services to her, and Edward VI, he received a grant and confirmation of his estates to hold them forever of the crown by the same rents and services as any of his ancestors. He sat in parliaments by the title of Thomas FitzMaurice, Baron of Lacksnaway, vulgariter vocatus Baro de Kery.

He and his son Patrick were subsequently involved in the rebellion. In the period following 1579, Sir John of Desmond having been executed in 1582 and the Earl of Desmond nowhere to be found, the government began to feel secure that the Celtic spirit of the province was entombed in the bowels of the earth and reduced its army to about three hundred foot and horse.

Upon this reduction, the 16th Lord Kerry and his son saw an opportunity and entered the town of Adare and attacked the greater part of the men there, attacked the castle of Lisconnell, throwing the English soldiers over the walls. Lord Kerry was pursued by Captain Dowdal who overtook him near Glenflesk and defeated him there, killing nearly 200 of his men and taking all his provisions, 800 cows and 500 horses.

Lord Kerry applied to the Earl of Ormond by whose influence a pardon was granted to him. He died at Lixnaw on 16th December 1590. Governor Zouch refused his burial in the family vault and he was buried in the tomb of Bishop Stack in the old cathedral of Ardfert.17

His son Patrick Fitzthomas Fitzmaurice, 17th Lord Kerry, born in 1541, was sent to England when very young as hostage to Queen Mary. He had only returned to Ireland after twenty years when he joined Desmond.

O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone came into Munster in 1599 and the 17th Lord Kerry brought a great number of men to the side of his relative, the Sugan Earl. Carew, at Carrigafoyle, sent Maurice Stack to Liscahane Castle who surprised the insurgents who were there in occupation and put the Irish warders of it to the sword.18

Soon after it was retaken by the Fitzmaurice family. Carew sent Sir Charles Wilmot into Clanmaurice where he attacked Lixnaw Castle and placed a garrison there.19 He attacked and took possession of Rattoo and subsequently came to Liscahane Castle which he restored once again to the English.

In 1600 Lord Patrick demolished the fortifications of Beal Castle.

However, the sight of his chief seat at Lixnaw possessed by the English caused him great grief and he died on 12th August 1600 at Downlogh and was buried with his uncle Donald, Earl of Clancare, in Muckross Abbey (Irrelagh).21

He was succeeded by his eldest son Thomas, 18th Lord Kerry. Thomas was born in 1574 and resided peaceably at his castle of Ballybunion, the English garrisoned at Lixnaw.22

On the death of his father, he sought the protection of the English through his wife, sister of the Earl of Thomond, but was refused and his castles and territories were attacked.

In August 1600 Maurice Stack was invited to dine with Lady Kerry at Beal Castle during the course of which she accused him of abusing her at which Stack was murdered and thrown out of a high window into the courtyard. Lord Thomond refused to see his sister after this incident and she died within a year.

In September 1600 Lord Kerry’s castle of Ardfert was attacked by Wilmot in a conflict that lasted nine days. Lord Kerry surrendered and all were taken prisoner with the exception of Constable John (Shaun Mollohagh) Fitzmaurice who was hanged outside Ardfert.

On 5th November 1600 the castle of Listowel, the last and only stronghold of Lord Kerry, was besieged and taken by Wilmot.

On 21st December the queen sent express directions that ‘in every pardon granted to Irish rebels there should be an exception that the name should not extend to Thomas Fitzmaurice, son of the late Baron of Lixnaw.’

Lord Kerry continued in arms and in 1602, Wilmot arrived at Lixnaw and there found Gerald Fitzmaurice, brother of Lord Kerry, with men assembled. Lixnaw was again in the hands of Lord Kerry. Wilmot cut off the water supply to the castle from the nearby river and ultimately Gerald Fitzmaurice capitulated. Lord Kerry finally made submission to King James I in 1604 whereupon he was pardoned and his estates granted to him by letters patent.

It is said that with his submission, the family became Protestant. Lord Kerry died at Drogheda on 30th June 1630.23

He was succeeded by his eldest son Patrick, 19th Lord Kerry, born in 1595. He sat in parliament in 1634 but after rebellion broke out in 1641 Patrick was appointed Lord President of Munster as a token of his loyalty. He raised an army to support English law and appointed Pierce Ferriter captain, who later carried off the arms for faith and fatherland.

Lord Kerry quitted his castle of Ardfert on 13th February 1642 and fled to England where he died on 31 January 1660. He married Hanora, daughter of Sir David Fitzgerald of Ballymaloe, Co Cork, eldest son of Sir John Fitzgerald of Cloyne, who survived him by 29 years.24

Lord Patrick was succeeded by his eldest son William, 20th Lord Kerry, born in 1633, who married Constance Long, a member of a Yorkshire family. Constance was the first Saxon spouse of a Lord of Kerry in the long line of descents and was deemed by her husband worthy of having a church built and a handsome altar tomb within it to her memory.

Close to Lixnaw in a state now of irretrievable ruin, of modern date though in an ancient burial ground, stands the church of Kiltomy. Two slabs fixed in the south wall now fallen to the ground and almost illegible tell its history:

This church was built and monument erected in the year of our Lord God One thousand, Six hundred and Eighty-five by the Right Honourable Lord Baron of Kerry in memory of his virtuous and well-beloved Lady Constance who dyed the 12th day October and was interred.25

He died in 1697 and was succeeded by his eldest son Thomas, 21st Lord Kerry. Thomas, born in 1668, sat in the Irish parliament for County Kerry in 1692 as Hon Thomas Fitzmaurice and took his seat in the House of Peers on 17th August 1697. George I advanced him to Viscount Clanmaurice and 1st Earl of Kerry on 17th January 1722 and in May 1726, he was called to the Privy Council.

He married 14th January 1692 Anne Petty, only daughter of Sir William Petty. Thomas died at Lixnaw in March 1741 leaving issue by Anne five sons and three daughters. Before he died he selected a burial place for himself apart from his whole family on the slope of a green hillside at east Clogher about a mile from his mansion where he erected a plain monument (Lixnaw Monument) in a vault below which he sleeps today.26

His eldest son William, 22nd Lord and 2nd Earl of Kerry, baptised in Dublin in 1694, was a colonel in the Coldstream Guards and in January 1721, was appointed governor of Ross Castle. On 24th October 1743 he took his seat in Parliament and in 1744 became a member of the Privy Council and was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Kerry.

He married Gertrude Lambart, daughter of Richard, Earl of Cavan on 19th March 1738 and dying at Lixnaw on 4th April 1747 left Francis Thomas, born in Dublin on 9 September 1740 and a daughter, Lady Anne, born at Ardfert in October 1741. 27

Francis Thomas succeeded his father as 23rd Lord and 3rd Earl of Kerry. He married Anastatia, daughter of Peter Daly Esq MP of Queensbury, Co Galway and resided for a considerable part of his life at Petersham in Surrey. After the death of Anastatia in 1799, ‘he regularly repaired to Westminster Abbey at three o’clock daily to pray at or near the tomb of his deceased wife.’28

He died at his residence in Hampton Court Green on 4th July 1818, without issue, at which time the direct line of the great family became extinct. 29

The title merged in that of the Marquis of Lansdowne, descended from John Fitzmaurice, second son of Thomas, the 1st Earl of Kerry.

It might be asked how the ancient house of Lixnaw came to fall. Francis Thomas, the last earl, having been involved with the wife of a Counsellor Daly, the learned Ponderoso took law proceedings and a verdict found against the Earl of Kerry for £40,000.30

The estates thus went under the hammer. The earl left the country and went into retirement in England and never returned and thus ended this illustrious Anglo-Irish sept.31

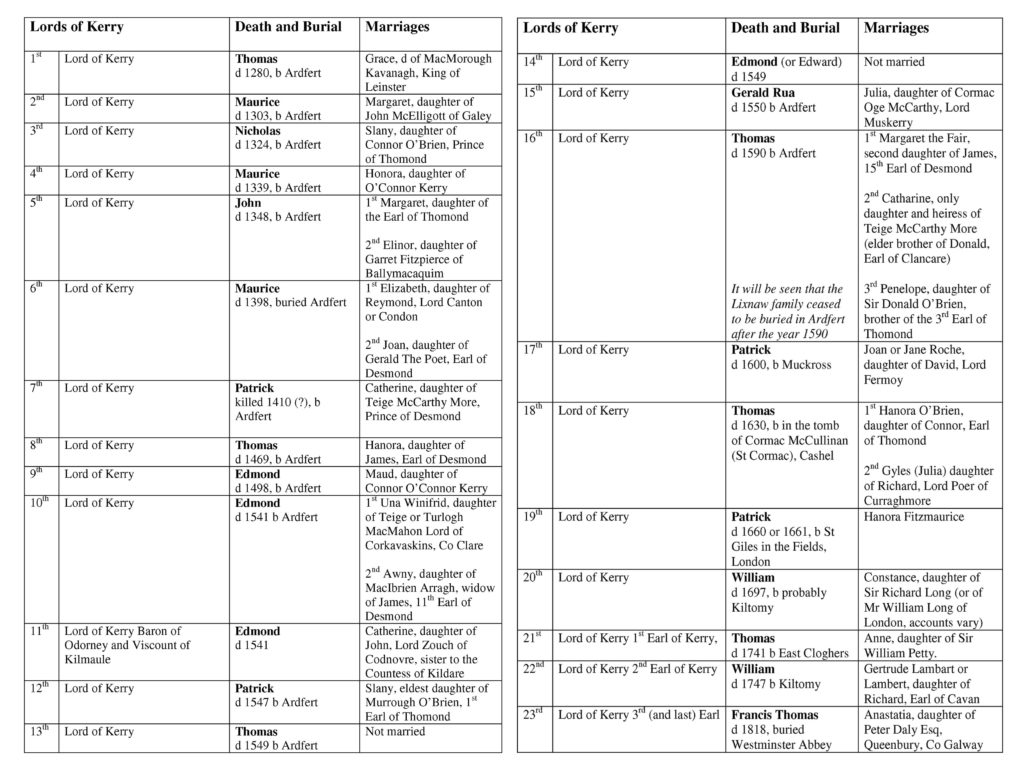

Lords of Kerry taken from old family records32

_______ 1 The document continued as follows:

-

That the said Patrick, for himself, his heirs, and all his people, are in other respects bound to answer the said Lord Earl and his heirs at their Assizes, in all appointments and levies whatsoever, in like manner as all others holding under the aforesaid Earl.

-

That should any controversy arise between the aforesaid Patrick and the son of McMorrish Geraldyn, or the sons of Richard McMaurice, or any tenants of the parties aforesaid … in such cases it shall be lawful for the aforesaid Earl to determine such controversy by his own arbitrament. If the aforesaid Patrick should rebelliously and disobediently refuse or omit to pay the aforesaid burdens, then the aforesaid Patrick binds himself and his heirs together with the lands, tenements and possessions of Fitzgemond, with its appurtenances, Boseday, Tullagh, with its appurtenances and Killuwragh, with its purtenances, to pay the aforesaid Earl and his heirs £300 in silver or gold, and customary money.

-

If the aforesaid Patrick shall not observe this agreement in respect to bearing the aforesaid burdens, then that Gerald Fitz-Dermod, John Fitz-John, Fitz-Maurice, Fitz-John, Thomas Fitz-Patrick Stacke, Captain William Fitz-Richard Stacke, Maurice Fitz-Redmond Stacke, bind themselves and each of them, their lands and tenements, goods and chattels, in twenty pounds (about £300 [1897]) of good and legal money, to be paid by any of them, in case the obligation to pay and support said burdens, to the said Earl shall not be discharged.

-

That Fitzmaurice is released from all past burdens of the said Earl.

-

The Earl is to protect Fitzmaurice when attending the Assizes or ‘going and returning’.

-

The Earl grants Fitzmaurice all the offices which his ancestors held from the Earl’s predecessors.

-

It guarantees ‘to defend and stand by’ Fitzmaurice throughout all his territory, against all and sundry, as well as all his other tenants, at the costs and charges of the Earl and the said Patrick. And for the greater security that the said Patrick (Fitzmaurice) and those of his people aforesaid will faithfully observe all and singular the said promises they have by their corporal oath submitted themselves to suspension, excommunication, and interdict of the Venerable Lord Bishop, Nicholas of Ardfert, which said Lord Bishop engages to fulminate the said censures against them as often as by the aforesaid Earl he shall be required, in case the said Patrick and the rest of his people shall be found wanting in the observance of the aforesaid agreement.

Witnesses: The Lord Bishop of Ardfert; Master Williame Stacke, Archdeacon of Ardfert; Henry Hubbart, and others. Seal of the Bishop of Ardfert. 2 This account of the Battle of Lixnaw was written by Fr J Prendergast of Killarney Friary as part of a history of Muckross Abbey and published in the Kerry Sentinel in the late nineteenth century. Muckross Abbey: A History (2018) will be published shortly. 3 Fr Prendergast added (in 1898): ‘Mr Bryan MacSheehy, Dublin, late Head Inspector of National Schools, is the lineal descendant of this Chief Constable or Field Marshal of the Desmond forces in the Elizabethan wars. The only representative of the great MacSheehy family in the female line in Kerry is Mrs James Curtayne, Belleville, Killarney, Apostolic Syndic of the Friary at Killarney.’ The following obituary was published in 1899: ‘In recording the death of Bryan MacSheehy Esq, HI NBE LLD, this last of the great and illustrious family of the MacSheehys of Kerry, we have the melancholy duty of chronicling the extinction of one of the oldest and bravest families of our kingdom. The MacSheehys, like the MacSweeneys, were the free lances of all our Anglo Irish wars during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries and always the ‘bravest of the brave’ …They were originally standard bearers of the MacDonnells of the north from whom they descended … In the year 1583 we find the illustrious Morrogh Bochagh, son of Edmund Sheehy, dying of a broken heart at Tralee on account of the murder of his liege lord, the Earl of Desmond, to whom he was secretary and confidential friend during many years of that last and most unfortunate of the great Geraldines … Bryan MacSheehy Esq was the eldest son of Michael MacSheehy Esq of Ballycarrig … this branch of the MacSheehys was allied to all the old Catholic families of Kerry, the O’Mahonys, the MacDonoghs, the Curtaynes, the MacSweenys, the O’Moriartys, the McCarthys, the Murphys, the Fagans and the Coppingers and Morroghs of Cork … Bryan MacSheehy was born in the family mansion at Ballycarrig on 16 June 1828 and at the age of 71, died on the 26th September 1899’ (obituary and genealogy, Killarney Echo, 11 November 1899). ‘Died on Tuesday morning in the prime of life Jane, wife of Michael MacSheehy Esq of Clahanemore’ (Chutes Western Herald, 9 May1833). ‘We feel much pleasure in announcing that Michael M’Sheehy Esq of Clahanemore in the County of Kerry has been appointed an Inspector of Schools under the National Board’ (Kerry Evening Post, 14 March 1838). It is not clear where ‘Ballycarrig’ was situate. In Kerry, the townlands of East and West Ballincarrig (or Ballynacarrig) lie in the parish of Aglish. One Michael MacSheehy Esq of Clahanemore held land at East Ballincarrig, Barony of Mahonihy, in 1829. Fr Prendergast also observed that the daughter of Nicholas MacSheehy of Limerick married John Browne of Hospital in 1540 from who descended the noble House of Kenmare in the female line. 4 The ruin of Lickbevune Castle, otherwise Leac-Beibhionn, Lackbevune, Lick or Leck, lies at Leck Point in the parish of Kilconly in North Kerry (GPS 52 34 33.017 -9 36 33.457). Image shown here from ‘Promontory Forts and Allied Structures in Northern County Kerry. Part I. Iraghticonnor’ by Thomas Johnson Westropp, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Fifth Series (1910) Vol 40, No 1, pp6-31. 5 The nephew of Conor Fion, who was slain at Lixnaw in 1568, was called John of the Battles from the many wars he waged against Elizabeth at the side of the unfortunate Earl of Desmond. He was chieftain or head of the family during 60 years. His brave and ‘almost unparalleled’ retreat under Donald O’Sullivan from Glengarriff to the country of the Rourkes is celebrated in all our modern histories. Conor Fion (the Fair), a Chief of this Sept, who also fell at Lixnaw in 1568 fighting against the Fitzmaurices, is mentioned in this year by the Four Masters. ‘There was one in particular slain there, whose fall was the cause of great grief, namely O’Connor Kerry (Conor the son of Connor); his death was one of the mournful losses of the Clauna Rory at the time; the lively brand of the tribe and race, a junior to whom devolved the chieftainship of his native territory, in preference to his superiors; a sustaining prop of the learned, the distressed, and the professors of the arts; a pillar of support in war and contest against his enemies, the foreigners’. A chapter on the family of O’Connor Kerry is contained in Muckross Abbey: A History (2018) to be published shortly. 6 The ruin of Ballymacaquim (Baile-mhic-an-Chaim) Castle is situate at Ballymacaquim East, parish of Killahan. The north west walls still remain. 7 Reference, ‘Some Kerry Mortuary Inscriptions, &c’, Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol 4, No 19 (Oct 1917), p202. The article was reproduced from a letter to the editor published in The Kerry Magazine, August 1854, entitled ‘Destroyed Tombs’, pp121-123. It was signed ‘Scrutator’, 8 ‘Benin was sent from Patrick to Ciarraighe as he sent Erc from him to the work he did not do – give the people of Chiarraighe to faith’ (An Seabhac). The townland was later named Monument. John O’Donovan, in his name books of 1841, parish of Kilcarah (Kilcaragh), observed, ‘In the townland of Monument Farm on a round hill which commands a fine prospect of the adjacent country, stands a monumental tower, in which the second last of the Earls of Kerry lies interred. This monument occupies the site of a church called Kilbinnaun (or Kilbinane), ie the church of St Benignes, from which the townland now called the Monument Farm was formerly called and which ought to be its name still, as the monument is not a century old.’ Almost forty years after O’Donovan’s observations, the poor condition of the monument was called to public attention, ‘At a very little cost this grand old reminiscence would be put into repair. The gentleman who owns the farm on which it stands, Mr Jeremiah Behan, and his father who held it before him, were most particular about the preservation of the monument but despite what can be done it is fast falling away’ (Kerry Evening Post, 4 September 1878). A lecture, ‘Some Historic Ruins of North Kerry’, delivered by Richard O’Shaughnessy at the Carnegie Library Listowel on 3 November 1919, included ‘the unsightly mausoleum at Lixnaw’ and gave its date of erection as about 1747. 9 Kerry Champion, 11 August 1934. ‘It sheltered the dead body of the greatest tyrant that ever served his imperial masters. It is without doubt a monument to British rule in Ireland and allowing it to stand there is but perpetuating the forms of injustice that were practiced to a great extent on a defenceless people’. 10 The description continued: ‘Large window shaped niches were prominent both on the external and internal sides of the tower while these were duplicated in the inside of the tomb. The whole structure was protected by a 12 foot high wall, the distance between the wall and the tower being several feet … The tricolor was a familiar sight on the pinnacle of the monument during the time of the Black and Tans but neither the Tricolour nor the monument can be seen today. It was blown up and destroyed by the Kerry County Council 25 years ago’ (Kerryman, 10 September 1982). The date of demolition is given as 10 September 1957. In 1958 the land was acquired by Kerry County Council for quarrying. Given its location, it is difficult to understand the reasons for the destruction of the monument other than to allow for quarrying at the site. Photographs of the monument in 1956 during quarrying on the Feale Drainage Scheme are held in the Kennelly Archive. In 1959, a silver coin was unearthed by workmen during quarrying operations there which belonged to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and bore the date 1585 (Kerryman, 6 June 1959). 11 The account was published in instalments in the Tralee Chronicle, 16 May 1865, 2 & 6 June 1865, 7, 11 & 25 July 1865, 1 & 4 August 1865 under the penname Senectus of Ardfert, who also contributed an article on the history of Ardfert to the same journal (‘Ardfert in Times Past and Present’, 1 November 1864). The articles have been edited with a small number of supporting footnotes. The identity of ‘Senectus’ who may have also used the name ‘Scrutator’, is not known. The following have been speculated on and mostly ruled out by Tralee historian Russell McMorran and Janet Murphy: Rev John O’Connell (later archdeacon of Castleisland), Rev Denis O’Donoghue, parish priest of Ardfert and author of Brendaniana (1893) and Thomas De Cantillon Church (1845-1884). 12 Lazar House was thrown down a few years ago by the lord of the soil and the stones taken away for other uses. An old Franco-Hibernian named Feviere lived in this house up to about ten years ago [1855]. It was thrown down about six years ago by Mr Crosbie. What a pity. It is said that a subterranean passage leads from this old house to the Grey Friary. When it was being thrown down we actually saw ourselves an arching under the walls which may be the opening of the passage, if tried. 13 ‘There were no less than four or five castles in Ardfert’ (Tralee Chronicle, 11 July 1865). The ivy-clad ruin of Port (or Purt or Portrinard) Castle, Abbeyfeale, can be seen on the Great Southern Trail. 14 ‘The Island of Kerry, and the whole Seigniory thereto belonging passed as dower to Earl Maurice by his second marriage with Ellenor, daughter of FitzMaurice, third Lord of Kerry and Lixnaw’ (‘The Earls of Desmond’ by James Graves, The Journal of the Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Vol I, 1869., p473). Maurice and Elinor had two sons, Nicholas and Gerald. Gerald ‘The Poet’ was 3rd (or 4th) Earl of Desmond and died c1397. The father of Maurice, 1st Earl of Desmond, was Thomas-A-Nappagh or Thomas-an-apa Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, 3rd Lord of Decies and Desmond. The appendage is explained as follows: ‘Thomas, being in his swaddling cloaths accidentally left alone in his cradle, was by an Ape carried up to the battlements of the monastery of Traly, where the little beast, to the admiration of many spectators, dandled him to and froe, whilst everyone ran with theire beds and caddows, thinking to catch the child when it should fall from the Ape. But Divine providence prevented that danger; for the Ape miraculously bore away the infant, and left him in the cradle as he found him, by which accident this Thomas was ever after nicknamed from The Ape’ (‘The Earls of Desmond’ by James Graves, The Journal of the Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Vol I, 1869. p462) . Thomas married Margaret, daughter of Walter de Burgo, son of Walter, Earl of Ulster. He died in 1298 and was succeeded by his son Maurice FitzThomas, 4th Lord of Decies and Desmond, created 1st Earl of Desmond and Lord Palatine of Kerry on 27 August 1329. Further reading, The Legend of Lough Brin and other Irish Legends (2017), ‘The Earl, the Monkey and the Battle of Callan’, pp39-42. 15 ‘He tooke Morrice Fitz Maurice Lord of Kerrie prisoner and sterved him in prison. He was the first of the English blood that yunforced coyne & liverie upon his tenants. The peere of Ireland that refused to come to the Kinges Parliament, being summoned. The first that by extortion and oppression enlarged his territories, and the first that made distinctions between English blood and English birth. This Maurice Fitz Thomas attended John Darcy Lord Justice of Ireland when he invaded Scotland, Anno 1334’ (‘The Earls of Desmond’ by James Graves, The Journal of the Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, Vol I, 1869. p473). 16 The deed referred to above was signed in 1422. Clearly a discrepancy exists in the date of this document or the date of Sir Patrick’s death. 17 His wife died during the Desmond wars and was buried in Muckross Abbey (Irrelagh). The Annals of the Four Masters record the burial under AD 1582: ‘Cathleen, daughter of Teigue son of Donal, son of Cormac Ladrach MacCarthy, the wife of FitzMaurice of Kerry, died. Her funeral proceeded to Lochlein-Linfiaclaigh, and her remains were conveyed from one island to another through fear of the plunderers, and were interred in the Monastery of Oir-Bolach (Muckross). 18 Note on Liscahane Castle: The ground about the place is very level and by no means high while the site itself resembles in every way one of those huge Danish forts that turn up before us through the country and was completely surrounded by a deep circular lake which was enclosed by a large and very strong fosse. Thus the castle was shut in and securely fortified while access to and fro was by means of a draw-bridge which spanned the lake and upon which was erected a portcullis. The castle belonged to a younger branch of the Lixnaw family before it was attainted by Elizabeth and given to Sir Edward Denny by whom it passed to an Englishman, Edward Gray, This lake was about 30 feet in breadth and every trace of it remains still but it is now passable and pastured, it having been filled up with earth and stones and debris of the old castle some fifty years ago by the Denny family in whose hands the land is still. Of the old castle not a trace or vestige now remains, the whole place being carpeted over with nature’s downy velvet. Many a sunny summer eve the writer of this spent on its verdant and historic apex (Tralee Chronicle, 23 June 1865). 19 In 1841, no part of the original castle was observable. 20 There is no trace of Beal Castle, in the parish of Kilconly (GPS 52 34 33.017 -9 36 33.457). 21 The following is from Mary Agnes Hickson’s historical records regarding a daughter of the 17th Lord Kerry: ‘Donogh MacGillacuddy, eldest son of Connor or Cornelius MacGillacuddy of Castle Currig, chief of the Sept in 1620 by his wife, the daughter of John Crosbie, Bishop of Ardfert in 1613, and his wife Joan, daughter of an O’Lalor of the Queen’s County. The bishop’s wife seems to have brought up her eldest son, Sir John Crosbie, and her four daughters (who all married Roman Catholic gentlemen) in that faith but her younger son David, who succeeded to an estate in and around Ardfert, adhered to his father’s creed and was a Protestant Connor, or ‘The MacGillacuddy’, as the old Celtic title ran, often dropped when the chances of war and political exigencies made it expedient to Angliccise names, died in 1630. His Funeral Certificate, preserved in the office of the Ulster Kings’ Record Tower, Dublin Castle, and an Inquisition taken at Killarney on the 16th April 1633 (before Henry Harte, gent; Colls Joy, gent; and Thomas Joy Esq) state that he left three sons, viz, Donogh, the above testator, aged ten years and nine months in 1630; Donnell and Connor and two daughters minors and unmarried. The Inquisition further states that the deceased Connor, alias Cornelius MacGillacuddy, was seized in his lordship as of fee of Ardlaghas (Ardglass?) and Bauncloon (the modern Whitefield), of Cahirdonnellieragh, Ardshilane, Gowlans, Glaneloghy, Callinafercy, Bracaharagh, Annagarry, the tow Carrunahones, Carrubeg, Gortnessig and Ardea, the last three of which he had demised to Dermot O’Leyne of Kiloytran … Dermot O’Leyne seems to have been the maternal grandfather of Connor MacGillacuddy because Sir George Carew in his mss preserved at Lambeth Library, written in or about 1590-1600, says that Donell, youngest son of Owen O’Sullivan More (whose name is inscribed on the ruined Dunkerron Castle) married the daughter of Dermot O’Leyne, widow of the Macgillacuddy. Donogh, the testator of 1696, must have been born in or about 1620-1 if the statement of his age in the Killarney Inquisition of 1633 be correct … In 1641 he was married to his cousin Mary O’Sullivan, youngest daughter of Donell O’Sullivan Mor by his wife, the Hon Joan Fitzmaurice, daughter of Patrick, 17th Baron of Kerry and Lixnaw and grandniece of Gerald, the last Palatine Earl of Desmond killed at Glannageentha in 1583’ (Kerry Evening Post, 17 May 1893). 22 Otherwise Ballybonany Castle, Bale or Bonan Castle. Further reading, Cavern of the Seven Daughters A Legend of Ballybunion Castle (2018). 23 ‘The burial in Cormac MacCullenan’s tomb at Cashel seems strange, for we read that he died at Drogheda in 1630; and seeing that his remains were moved thence for interment, it appears remarkable that they were not brought to the burial place of his ancestors’ (‘Some Kerry Mortuary Inscriptions, &c’, Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol 4, No 19 (Oct 1917) p202). 24 Authorities differ on the father of Hanora viz Sir James Fitzgerald of Carrigaline or Sir Edmond Fitzgerald of Ballymaloe and Cloyne. Some strange tales are told of Hanora, one of which tells how she fooled a clergyman, Maurice O’Connor (later Archdeacon of Ardfert, a convert from Catholic to Protestant) by feigning approaching death and requesting his administrations. She pressed him on the surest way of salvation and he assured her it was the Catholic faith. For this she cried out and tried to expose him but when the servants rushed to enter the room, she was in a state of syncope. She died soon after and was buried in the small transept attached to the old cathedral: This monument was erected and chapel re-edified in the year 1688 by the Right Honourable Honora, Lady Dowager Kerry, for herself, her children and their posterity only, according to her agreement with the Dean and chapter. The general belief was that she was anathematised by the minister who possessed as priest superhuman powers. Her remains never fell into a state of decomposition but became withered and shrivelled and so remain. ‘We saw the body, which has become a curiosity, some three years ago and can vouch for this but whether this has been wrought by way of embalmment or the malediction of O’Connor we cannot say. Thomas De Cantillon Church remarked that a few years ago the embalmed remains of this lady were dragged from the tomb by the unhallowed curiosity of the peasantry, flung about and exposed to the public gaze and tumult in the most revolting manner.’ 25 John O’Donovan, in his name books of 1841 (parish of Kiltomy) cites a tablet in the south wall of the church near the south east corner, indicating the church was built in 1623. 26 There is a story still about the 1st Earl of Kerry’s connections with the Lambarts or Lamberts of Cavan and worse again when it descended to his son, Lord William, on his marriage with Gertrude Lamberte. This union was against his wishes and so appalled was he at the connection that he presaged the ruin of Lixnaw House in another generation and built a monumental urn for himself away from the family vault hence the Lixnaw Monument. ‘The only members of this family buried in The Monument at east Clogher in Clan Maurice was William the first Earl of Kerry and possibly his son and successor. It was reported that in the rebellion of 1798 one or two lead coffins were taken from this monument and converted into bullets for the use of the rebels. If so, they were probably the coffins of the last mentioned noblemen’ (‘Some Kerry Mortuary Inscriptions, &c’, Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol 4, No 19 (Oct 1917) p202). In a lecture delivered by Richard O’Shaughnessy in 1919, it was stated that the monument was ‘built over the remains of the second Earl of Kerry about the year 1747’ (Kerryman, 15 November 1919). Various sources also give the date of erection as 1692. 27 Further reference, The Right Honourable Francis Thomas, Earl of Kerry and Lixnaw, in the Kingdom of Ireland, an infant, by the Right Honourable Robert, Baron Newport of Newport, in the said Kingdom, his guardian and next friend. appellant. The Right Honourable John Petty, Lord Viscount Fitz-Maurice, in the said Kingdom of Ireland. respondent. The case of the respondent (1752). 28 ‘Some Kerry Mortuary Inscriptions, &c’, Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol 4, No 19 (Oct 1917) p202. 29 A near relative, Mrs Hinde, sole executrix. 30 The case of Charles Daly Esq against Anastatia Daly can be read in Trials for Adultery: or, The History of Divorces (1779) pp1-40. The Earl of Kerry was married to Mrs Daly, sister of the Countess of Lough, and of the Countess of Kingsland, at South-hill in Berkshire in 1768. She died in 1799, at which time the Earl of Kerry retired to seclusion. 31 Further reading, The Fitzmaurices, Lords of Kerry & Barons of Lixnaw (1993). 32 See also ‘Some Kerry Mortuary Inscriptions, &c’, Kerry Archaeological Magazine, Vol 4, No 19 (Oct 1917), pp199-204 (reproduced from the Kerry Magazine, August 1854, ‘Destroyed Tombs’, pp121-123).