Erin! Beloved motherland! May Kerry’s dead inspire Our youth today to take its stand, Alert with olden fire. For Erin and her freedom too, All round from sea to sea, May all her children still be true, Like those of Oilean Chiarraighe.[1]

Insular art is an impressive and imposing feature of the Irish landscape, a wholly recognisable symbol of ancient societies, connecting old to new.

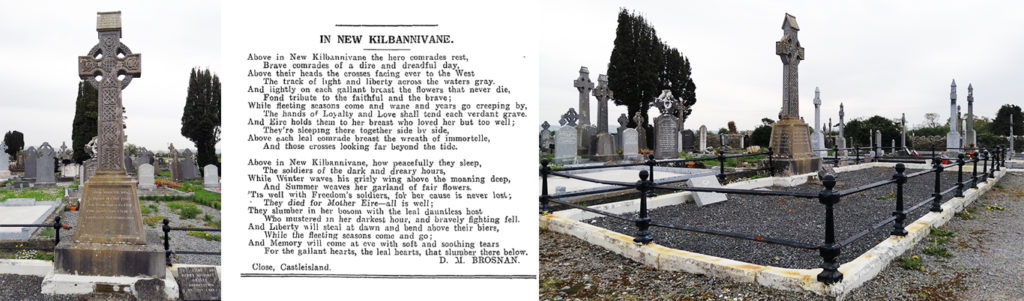

Castleisland has its share of this art form. In Kilbannivane Cemetery stands a handsome monument to commemorate the place where rest thirteen soldiers of the Castleisland Battalion of the Irish Republican Army, who fell 1916-1923.

The Tricolour hung in graceful folds above the Republican Plot which was becomingly decked with flowers and evergreens … a work of perfect art stands there in New Kilbannivane forever[7]

On Sunday 6 October 1929, in dire weather conditions, some 3,000 people gathered in Castleisland to form a procession – headed by the Killarney kilted pipers’ band – which started at the ruin of Desmond Castle. The spectacle can only be imagined as the procession moved through the town to Kilbannivane cemetery for the unveiling ceremony.

The Celtic Cross, draped in black, was the work of sculptor, P O’Reilly, Castleisland. It was carved from Duhallow limestone,12 feet, 8 inches high, interlaced on four sides with drawings from the Book of Kells, its panels ornamented in old Irish scroll work. It was supported on a pedestal of die stone and inscribed:

I gcuimhne brodach agus gradach na ndaoine so a thuit in san troid ar san saoirseachta a dtir o 1916 go 1923 agus a bhfuil a nainmneacha mar ieanas annso: Michael O Brosnacain Tomas Pleimionn Risteard O Seanachain Seaghan De Prendibhile Cormach O h-Analain Partolan O Murcadha Scaghan O Sabhain Padraig O Buachalla Seaghan O Dalaigh Micheal O Conaill Seumas Breathnach Diarmuid O Laoghaire Padraig O Ceannaigh[8]

The erection of the Celtic Cross was the result of a fund raising initiative by a committee headed by T T O’Connor, Cordal. Financial aid also came from committees formed in New York, Chicago and San Francisco, who worked under the direction of Sean O’Riada, New York.[9]

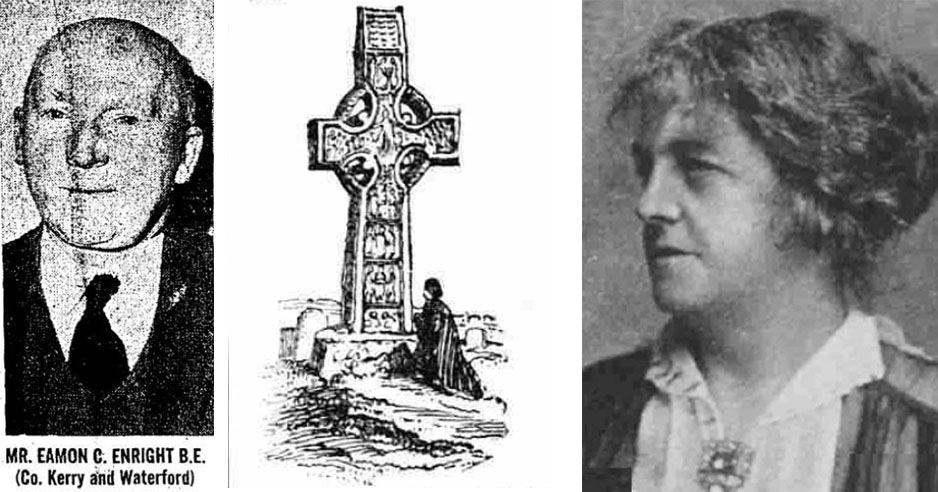

The monument was unveiled by Eamon O h-Ionnrachtaig, otherwise Eamon Enright. His eloquent speech, reproduced below in full, underlined the meaning of the occasion: to place on record with the greatest honour those who had given their lives in the cause of Irish freedom. The speaker, acknowledging the fulfilment of this desire, stressed that the Kilbannivane Memorial – decorated from the Book of Kells – was but ‘a fresh link’ in a chain to the struggles of the past, the ‘long chain of sacrifice.’ This chain, he informed his audience, was ‘a golden chain’ which linked age to age to the very moment in which they stood:

Here by the graves of our heroic dead it is well for us to take thought. By this public act of homage we join in communion of soul with all those of our race who in other times and in other places performed the same proud duty. We are the heirs both in the body and in the spirit of the men who bore Tone to his rest in Bodenstown and buried with that fiery heart the splendid hopes of a generation. Our faith is the faith of the trusted few who smuggled the headless corpse of Emmet in secret and by night to its obscure grave. We are one with the clansmen who laid the wasted body of Owen Roe in the clay before turning leaderless but undaunted to face Cromwell. We commemorate today not merely the men who lie around us and whom we knew in life but through them all that high and gallant company, the Irish dead. It is well to be mindful of these things. It is well to remember that the cause that filled these graves is of no new date, neither of yesterday nor of 700 years. In that same cause nine centuries ago aged Brian fell on the field of his fame. It is a far cry from our day to his but still farther, perhaps, from the great king, the wielder of armies, to those sons of the people who in small and scattered bands fought the same fight no less bravely. Yet they had much in common. Brian, too, lived the hard life of the irregular, hiding in woods and mountains, often with only a handful about him, striking his blows when he could, hunted and harassed, but never despairing. The very enemy was the same, for those whom he drove out what were they but the fathers of the Normans whom Ireland has ever since been striving to dislodge. These graves are fresh links in the long chain of sacrifice. The men who lie therein have entered the noblest brotherhood of patriots this world has ever known. These are high words, but they are used deliberately. Other nations have gone gaily to battle and fallen in face of numbers. We ourselves have seen a world upheaval where numbers were pitted against numbers and science on the one side harnessed itself against science on the other. But few nations have fought against such terrific odds of man power, equipment and resources as have the Irish. None have so repeatedly and in the face of such crushing blows renewed the struggle. The agony of Poland, of which so much has been heard, lasted little more than a century and a half. The struggle for Greek liberty was neither so long drawn, nor so sustained. Not even the history of the early church can show a longer or a nobler list of martyrs. In the ever recurring conflicts of the centuries this ancient country has taken no mean part. Among these hills the great Desmond line forgot their Norman blood; forgot their feudal pomp and old allegiance and softening in the kindly Irish air became more Irish than the Irish themselves. Over in Glanageenty the great Earl, the last of his line, fell at the hands of a traitor. His head was cut off, salted, and sent over to Elizabeth. Here Pierce Ferriter, impassioned poet, gallant soldier, cultured gentleman, maintained himself in arms against Cromwell long after the rest of the country had been compelled to swallow the British peace. Here he held the last outpost of Gaelic Ireland till he, too, fell, by treachery. In the Maine Valley, Eoghan O’Rathaille sang his songs, raising the courage of his countrymen, steeling their hearts against the foe. From the Cork-Kerry border came the first whispered stories of marching men and midnight drillings which heralded the birth of Fenianism. That our day and our generation had not been behind hand, let these graves bear witness. One may ask why, with so many and such noble adherents, the cause for which they died is still unattained, the battle un-won. We must first look to ourselves for the answer. The Irish Nation has, in every age, flung up men of high ideals, of great moral strength, and desperate courage. Their deeds have bound age to age with a golden chain of vast endeavour and heroic failure. But we are not all a nation of heroes. We have had our weakness, our apathy, our dissension, our war of brothers. We have had our faint hearts, our self-seekers, even our traitors. No people has risen to greater heights; few have sunk to lower depths. We have the Celtic fire but with it the lack of staying power that may be Celtic also. Irresistible in our moments of enthusiasm we chafe and falter at the grim and protracted struggle that calls for long endurance. Should proof be needed, look for it in our own time. Could these dead rise from the grave, would they recognise the new Ireland? Where are the courage, the high spirit, the aspirations which flamed in our people when these men lived and walked amongst us? And yet our sufferings are not to be compared to those of our fathers. In Elizabeth’s time so great was the havoc wrought in this very spot that an English observer recorded that one could traverse the length and breadth of Desmond without hearing the lowing of cattle or the voice of man. The men of 1798 suffered much more barbarously and in far greater numbers. Cromwell butchered more men, women and children in a day than fell in Ireland in our generation. Freedom is a glorious thing, splendid in its growth, dazzling and magnificent in the fullness of its strength, but it is born in blood. You may see in the rise of the Dutch Republic to what lengths a brave and stubborn people has gone in its zeal for liberty. Time and again in the struggle against the might of Spain the insurgent Dutch broke down the dykes that guard their hollow land from the sea, flooding the soil won by centuries of grinding toil. Time and again fields and homes and harvests were given over to the waves till the gallant people had little left save their swords with which to fight. Such an appeal to a just God was never made in vain. Holland is now a great nation, prosperous and enlightened. The dead beacon the way our steps should go. Homage such as this is either honest or a mockery. If we who render them lip service rest in contented apathy, then it would be more decent to forget them. But if we be false to the ideals for which they died, not on the heads of those who slew them but on our heads shall their blood be. They were brave and thirsted for justice. Do you likewise. A united people firmly rooted in the right has never been and never shall be broken. The rocks are harder than the sea, but the sea wears them. Right is weaker than Empire, but empires confronted with right loosen and crumble away. Time is strewn with the wrecks of vast dominions. They have their mighty day, and flourish exceedingly, filling the earth with their pomp. Then growing over-proud they crash to ruin. But a nation is indestructible, self-renewing, lasting as long as earth will last. We unveil today a monument of perishable stone. If we be true to the dead and to ourselves then one day we shall raise a monument that time will never take away – the one adequate and fitting memorial to our fallen soldiers of freedom. When this ancient nation, sundered by the seas from all lands and peoples puts on again her unity and her sovereignty and neither oppressing, nor oppressed resumes her olden mission of culture – then only shall we fittingly honour our dead.[10]

At the conclusion of Mr Enright’s speech, the last post sounded, and proceedings terminated.

Eamon Enright, Listowel

The selection of Listowel man, Eamon Enright for the ceremonial task was apposite. A little over five years earlier, he had been released from Mountjoy Prison barely alive, having participated in the mass hunger strike by Republican prisoners, which began in Mountjoy in October 1923, to protest at continued incarceration at the end of the Civil War.

The 21-year-old went without food for 48 days, ‘tortured and broken in health’ but ‘like so many Kerry boys, he stood for the glory of the Republic.’[11] He was released from Mountjoy in December 1923 and spent eight months in hospital.[12]

In the years that followed his recovery, Eamon, who wrote poetry, read widely, and was conversant in Irish, French and German, appeared on the committee of the Gaelic League in Tralee, and delivered a number of orations in the county, including one at the Republican plot in his hometown of Listowel to commemorate ‘the men of all generations who gave their lives for Irish freedom.’[13]

He later lived in Dublin and numbered among those who represented the Republican organisations at the funeral of Austin Stack in April 1929. In that year, he joined the ESB and in November 1930, as Assistant District Engineer, went to live and work in Waterford. A few years later he was appointed District Engineer. He was president of the Waterford and Lismore Diocesan Hospitalite de Notre Dame de Lourdes.

On 25 April 1932, in Waterford, he married Catherine, eldest daughter of wool merchant, Thomas Wyse Power, whose American born wife Letitia (1871-1924) was proprietress of the Hotel Metropole, Bridge Street, Waterford.[14] The hotel was said to have been favoured by Eamon de Valera.

Thomas, one of the nine children of James Power (1832-1895) and Catherine Wyse (1837-1901) of Carriganore, Knockhouse, Waterford, was brother of journalist and Irish nationalist, John Wyse Power, whose wife Jennie, daughter of Eamonn O’Tuathaill (O’Toole), was Senator of the Irish Free State from 1922-1936.[15]

Eamon and Catherine Enright had one son, Pat. Mrs Catherine Enright of Church Road, Tramore, died on 16 July 1977. Eamon died in May 1981, survived by his son and a sister. In 1982, his library was donated to the Waterford Municipal Library.

___________________

[1] From ‘Castleisland Celebration of the Memory of the Dead’ by ‘Hawthorn’, Kerry Champion, 12 October 1929. Kilbannivane Cemeteries are situated in the townlands of Anglore, Bawnluskaha and Kilbannivane, Castleisland. [2] Image from Genealogical Memoir of the Family of Montmorency, styled De Marisco or Morres (1817) by Hervey de Montmorency-Morres. The image is captioned ‘Ancient stone cross at Armagh, 18 feet high, erected to Neill-Callan, King of Ireland ab anno 833 to 863 – His cross at Kilree is quite plain and much shorter.’ Neill-Callan drowned in 1846, his reign 832-846; his son, Edan VI, Finliat, King of Temoria, reigned 863-879. The dates on the caption appear to cover two reigns. The kings of this period, according to Catalogue of the Kings of Ireland from Laegarius (463), Son of Neal, till the coming of Henry II under whom that Island was made Subject to the Crown of England … As for the Predecessors of Laegarius, I have purposely omitted them because most of what is deliver’d of them (in my opinion) is either Fabulous or very much intermix’d with Fables and without Chronology in The Antiquities and History of Ireland (1705) by Sir James Ware (pp11-16) were: ‘Neal Cail or the Lean Son of Edan the V. Succeeded Concobar in the year 832. And was drowned at Callina, in the year 846. Aged 55. Melfeclin I for the better sound called Malachias son of Maelruan. Reigned 16 years and died in the year 862 and was buried at Clonmacnoise. Edan VI, Son of Neal, called Finliat, King of Temoria, succeeded and Reign’d almost 17 years, he died in the year 879, at Druim-Inisclain, in Terconall.’ The cross at Kilree, alluded to in Montmorency’s caption, is sited near Kilree Round Tower, Kilkenny. In 1825 it was described as ‘curious’ in The Beauties of Ireland: Being Original Delineations (1825) by James Norris Brewer, Vol I, pp489-490: At Kilree is to be seen a curious stone cross, about eight feet in height, and of great antiquity. The cross is formed from a single block of free-stone, and has no other ornament whatever than orbicular figures or rings, one within the other, placed on the centre and extremities of the fabric. According to tradition, this monument is referable to Neill Callan, monarch of Ireland, who is said by Macgeoghegan to have been drowned in the river of Callan in this county (since called Aunree or the king’s river) whilst vainly endeavouring to rescue a nobleman of his suite, with whom he perished in the stream. A footnote to the above stated: ‘In contradiction to the above tradition, it is asserted by some writers that King Neill did not perish in this neighbourhood [Kilkenny], but in the river Callan which waters the city of Armagh, and which is, assuredly, a more rapid and dangerous stream than the Aunree. The probability of the latter assertion is strengthened, in the opinion of its advocates, by the existence of a magnificent stone cross in the square fronting the cathedral church of Armagh, dedicated to the venerated monarch in question. Upon this subject it is correctly observed in the MSS of Chevalier De Montmorency, that crosses were frequently erected, as pious memorials, on places where the bodies of royal personages were temporarily reposited. Thus, when Brien-Boiroimh fell at Clontarf, his remains were first removed to Kilmainham Priory, and a cross was at that place erected to his memory, although his body was finally conveyed to Armagh for interment. The instances, indeed, of such erections are very numerous. In consideration of this custom, the learned and ingenious Chevalier believes the cross at Kilree to have been designed, as the very prevalent tradition asserts, in commemoration of King Neill, although, in common with that constructed at Kilmainham in memory of Brien, it cannot be thought to cover the ashes of the deceased. King Neill, who was probably drowned in the river Callan in this vicinity, was the son of Hugh VI, monarch of Ireland, and his premature death occurred about the year 860.’ It is not known if the cross remains ‘in the square.’ It is worth noting that there are two cathedrals dedicated to St Patrick in Armagh, Roman Catholic and Church of Ireland. Both are built on holy ground. The Church of Ireland structure (Cathedral Close, Armagh BT61 7EE) is built on the site where St Patrick is believed to have built his first stone church in the fifth century. The cornerstone of the Roman Catholic structure (Cathedral Road, Armagh BT61 9DY) was laid on St Patrick’s Day 1840 and it was completed in the early 20th century. [3] ‘It is the memorial of a grateful people to a landlord who is justly regarded as having been upright, and anxious for the welfare of his dependents. By its situation, it will prove a conspicuous object in a region where the wonders of nature are so remarkable, and we are quite sure it will be found on completion, a creditable specimen of Irish talent. It is to be a Celtic Cross of no less than twenty eight feet high, and it is intended to stand on the summit of the highest mountain upon the estate. The design has been furnished by Mr W Atkins who, in addition to the ordinary ornamental carving on such monuments, inserts two panels, one with a medallion of the deceased, and another with symbolic figures. The execution has been entrusted to Mr P J Scannell, like Mr Atkins, a fellow townsman’ (Tralee Chronicle, 13 December 1867). It is inscribed: In Affectionate Memory of The Right Honorable Henry Arthur Herbert Born 1815 Died 1866 His Tenantry have Erected This Cross to Record their Sense of His Virtue and their Grief for His Loss. [4] For an account of the erection of this memorial refer to The Diary of Robert O’Kelly (2015) published by the Michael O’Donohoe Project Committee. [5] The monument, 24 ft in height, was unveiled by the Right Hon Earl of Kenmare on 26 September 1906 on a site given by ‘the late Lord Kenmare on the Railway Hotel grounds … The Memorial, which was designed by Mr Frank Richards, 36 Victoria St, London is made of Kilkenny cut limestone and the enclosing of the site, the concrete foundation for the cross trunking and forming the grounds and the putting up of the stands were done by Mr P Murphy, contractor, Tralee’ (Kerry Evening Post, 29 September 1906). ‘The memorial has been erected on the boundary of Home Park’ (Mid Sussex Times, 2 October 1906). ‘It is the habit of certain circles in this country to regard the Irish soldier as an outcast. He is shunned, partly because his manners are said to render him unfit to associate with decent folk but principally upon the ground that by taking service under the Crown he has behaved as a traitor to the National Cause’ (Irish Times, 27 September 1906). A sign at the site states: ‘This Monument is Erected to the Memory of the Members of The Royal Munster Fusiliers from the Counties of Kerry, Cork, Limerick and Clare Who Died on Active Service in Burma, South Africa and West Africa 1881-1902.’ On the front of the monument is inscribed: Erected by the Counties of Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Clare and by their Surviving Comrades of The Royal Munster Fusiliers to the Glory of God and in Honoured Memory of The Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Men of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th Battalions who gave their Lives in the Discharge of Duty on Active Service. In the outer ornamentation is engraved (anti-clockwise): Plassey Masulipatam Buxar Carnatic Guzerat Bhurtpore Chunzee Sobraon Chillianwallah Pegu Lucknow South Africa 1899 1900 1901 1902 Burma 188(?) Delhi Goojerat Punjaub Ferozeshah Afghanistan Deig Sholinghur Rohilcund Badara (?) Condore. The left panel of the monument, in three columns, under heading Burma 1887-1888, records the following: Col 1 Pte (Private) T Allen Pte T Banks Pte A Bishop Pte E Blair Pte J Brien Pte J Burt Lt Cpl C Carpenter Dr S Campbell Pte J Campbell Pte J Carey Pte J Clifford Pte M Collins Pte D Crimmins Pte M Cullen Pte J Cusack Pte W Dickinson Pte P Doherty Pte J Donoghue Pte D Donoghue 59o Pte D Donoghue 1212 Pte T Donovan Pte D Donovan Pte D Dorgan Pte N Dunne Pte R Dunne Pte J Ervine Pte J Everett Sergt H Farmer Pte J Finn Pte W Finney Pte J Fitzgerald Pte W Foster Pte J Frahill Pte J Giggle Pte J Green Pte W Griffin Corp P Hymes Pte T Hanley Col 2 Pte M Hannon Pte J Harrington Pte J Harris Pte M Healy Pte J Hoare Pte M Holmes Pte C Jackson Pte J F Jones Pte M Kelly Pte M Kiely Pte J Kinlon Corpl W Lambley Pte J Lawless Pte C Logan Pte M Maguinness Pte M Magner Pte P Mangan Pte D Mills Pte W Mohan Pte J Moran Pte M Morley Pte C Mulcahy Pte J Murphy Pte T Murray Corpl D McGillycuddy Pte D McCarthy Pte J McIntyre Pte M McKenna Pte J McMahon Sergt T Norris Pte J Nealon Pte P Norris Sergt D O’Connell Pte W O’Brien Pte D O’Callaghan Pte W O’Regan Pte J Pearson Pte A Potter Col 3 Pte W Quinn S.I.M. E Rice Pte H Reed Pte J Rielly (sic) Pte J Roche Pte M Rourke Pte T Ryan Corpl J Scholey Pte J Sanderson Pte R Schofield Pte C Shanahan Pte J Sheehan 81 Pte T Sheehan Pte J Sheehan 2723 Pte Sherman Pte J Sliney Pte P Smith Pte P Sullivan Pte D Sullivan Pte M Sullivan Pte E Sullivan Pte D Sweeney Pte J Sweeney Pte S Thompson Pte A Turner Pte W Turner Pte S Turner Pte J Turphy Lieut C Williamson Corpl C Webber Pte M Walsh Pte C Ward Pte J Watson Pte R Watson Pte W Willerton Pte A Willis Pte A Winter Pte W Wyatt Pte M Young The right panel of the monument, in three columns, under the headings, South Africa 1896 Captain W J Harold-Barry West Africa 1900 2nd Lieut H J Burton South Africa 1899-1902 records the following: Col 1 Lt-Cpl E Ahern Pte J Ahern Lieut F R Brown Corpl E Buckley Pte C (or G) Bailey Pte J Barry Pte J Bourke Pte W Brown Pte J Buckley Pte W Burke Pte J Butler 2nd Lieut W C R Croker LcCpl (Lance Corporal) J Cahill Pte T Cambridge Pte D Cambridge Pte P Carlton Pte J Carroll Pte W Casey Pte B Chaplin Pte C Connors Pte T Cottrell Pte H Cournane Pte J Creedon Pte J Deegan Pte T Dennehy Pte M Donovan Pte K Driscoll Pte P Driscoll Pte J Fitzpatrick Pte J Flaherty Col 2 LcCpl C Grimes Pte M Grady Pte C Griffin Corp W Holloway Pte T Hallinan Pte R Healy Pte M Hogan 5852 Pte M Hogan 5529 Pte A Howard Pte R James Pte W (?) Jordan Pte P Kenny Pte P King Pte J Lagan Pte J Lawlor Pte M Leary Pte F Leary Pte W Lemaine Pte J Lyttleton 2nd Lieut C R Moore LcCpl P Moore Pte C Maher Pte J Malley Pte J Manning Pte J Moate Pte J Murphy 6017 Pte J Murphy 2083 Pte N Murray Corpl M McSweeney JCl (?) T Mc Dermott Col 3 Pte J McCarthy Pte T McCarthy Pte T McGrath LcCpl B O’Neill Pte D O’Brien Pte J O’Callaghan Pte J O’Donnell Pte M O’Halloran Pte T O’Keeffe Pte A O’Neill Pte M O’Shaughnessy Pte H Pratchett Pte M Quinlan Pte T Reidy Pte J Roche Pte J Ryan Pte P Ryan 2nd Lieut R C Shaw 2nd Lieut C N Shea Cr Sgt W Sullivan Pte H Searls Pte J Singleton Pte J Small Pte D Smith Pte M Sullivan Pte J Sullivan Pte J Synan Major R Whitehead Corpl T Walsh See also, The Story of the Munsters at Etreux, Festubert, Rue Du Bois and Hulloch (1918) by Mrs Victor Rickard, Dedicated to Victor Rickard and His Comrades in all Ranks of the Munster Fusiliers who Fought and Fell in the Great War 1914-15. A second monument alongside the above was unveiled on 24 September 2009 by Mary McAleese, President of Ireland, inscribed: ‘This Monument is Erected in Memory of those People from Killarney and Surrounding Areas who Served and Died in the 1914-1918 War Solas na bhFlaitheas ortha go Síoraí [6] ‘In New Kilbannivane’ by D M Brosnan, Close, Castleisland, published in the Kerryman, 30 November 1929. [7] Kerry News, 9 October 1929. [8] Kerryman, 12 October 1929. [9] The following committee had charge of the collection of funds and erection of the memorial: T T O’Connor, Cordal, chairman; Mossie Keane, Tullig, vice-chairman; Jack Shanahan MPSI Castleisland, secretary; Jerh Long MCC, Knocknagoshel, treasurer; Rev Fr Lyne CC Currow; Thos O’Neill, solicitor, Castleisland; David McCarthy, Brehig, Cordal; Humphrey Murphy NT, Ballybeg, Currow; Pat O’Connor, Dromulton, Scartaglin; Thos Lawlor, Castleisland; Michael Doody, Knockafreachane, Brosna; David McAuliffe, Brosna; Michael Doody, Knocknaghosel; Jack Walsh, Lyre, Farranfore; Wm Nolan, Carrigcannon; Michael Collins, Carrigcannon; Maurice Buckley, Scartaglin; James O’Connor, NT, Knocknagoshel; John Kerin, Scartaglin; James Lacy, Castleisland; Denis Prendeville, Cordal; M D Loughlin, Cordal; Michael O’Leary, Brehig; David Griffin, Castleisland. [10] Kerryman, 12 October 1929. Further reference, Dying for the Cause: Kerry’s Republican Dead (2015) by Tim Horgan. [11] Kerryman, 15 March 1924. [12] He was also interned in the Glasshouse, Curragh. 'We are informed from a Sinn Fein source that Mr Eamon Enright had been released from Mountjoy Jail and was brought to Miss O’Donell’s Nursing Home, Eccles Street' (Dublin Evening Herald, 12 December 1923). ‘A Republican Statement: The mental condition of E Enright grows worse and no nurses have been admitted to Mountjoy Jail since the strike. In Kilmainham, the Mayor of Limerick, Austin Stack and Tom Derrig are all seriously ill’ (The Liberator Tralee, 11 December 1923). ‘It was stated that Mr Enright was delirious and that his condition was considered to be very serious’ (Irish Independent, 12 December 1923). ‘On enquiry today at Miss O’Donnell’s private nursing home, 62 Eccles Street, it was learned that Eamonn Enright, a Co Kerry ex-hunger-striker, yesterday released from Mountjoy prison, is in rather serious condition’ (Evening Herald, 12 December 1923). ‘We are pleased to be able to say that Mr Eamonn Enright who has been in hospital ever since his release from Mountjoy Prison, after the hunger strike last November, is now completely recovered. He was discharged from hospital a few days ago but is remaining in Dublin for now’ (Kerry Reporter, 23 August 1924). [13] He contributed material to Ireland Today, July 1936. [14] The couple married at Piltown Catholic Church. Mrs Letitia Power applied for a transfer of licence from Quinn’s Hotel, Bridge Street, in 1904. Catherine and her sisters, Letitia and Mary Agnes, carried on the Hotel Metropole after the death of their mother in 1924. Letitia married in 1928 Sean F Lane, Principal of Waterford Tech. She kept a fancy goods shop in Michael Street, Waterford. She died in 1976. [15] Siblings included William, James, Catherine, who married Patrick O’Keeffe (1881-1973) and Anne, who married R F Phelan, Waterford Corporation. John Wyse Power (1859-1926) and his wife Jane Wyse Power (1858-1941) met when John was imprisoned under the Coercion Act (he was arrested in Baltinglass in December 1881). Jane (Jennie) was working for the Land League and distributing literature. In 1903, both learned Irish at Ring (Ringagonagh) in Dungarvan, Waterford. John Wyse Power subsequently wrote an article which helped to make known to students of Irish the Ring Gaeltacht (Gaeltacht na nDéise). Iol-scoil na Mumhan (or Muman) (University of Munster) was subsequently established at Mweelahorna, Ring, in 1905. It is now Coláiste na Rinne; further reference, Pádraig Ó Cadhla (1875-1948) at aimn.ie. They had three children, Maire (1887-1916), Nancy (born 1889-1963) and Charles Stewart (1892-1950). Charles married a sister of Michael J Quirke, solicitor, Carrick-on-Suir.