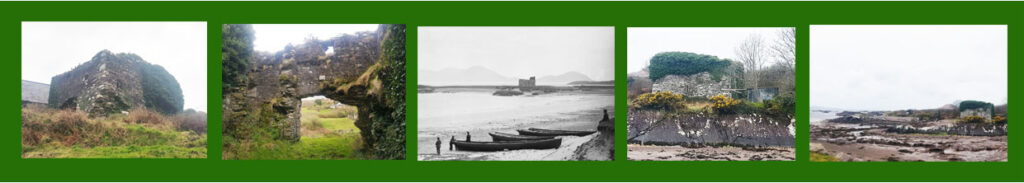

In the disturbed days of the reign of Elizabeth I, the sept of O’Sullivan of Caherdaniel decided to construct a castle at Ballycarnahan, their chief residence in the district.[1] O’Sullivan’s Tanist lived nearby at Liss. The two men were compelled to go away and fight in the Elizabethan wars.

The Tanist’s wife considered herself superior to the lady of the head of the house of O’Sullivan.[2] In her husband’s absence, she decided to build her own castle on the water’s edge at Bunaneer, not too far distant from Ballycarnahan.[3]

The walls of Bunaneer – like Ballycarnahan – were hardly raised when the Tanist returned from the war injured and impaired in sight. He soon discovered what his lady had been doing during this interlude and was furious with her. He realised, in those tempestuous times, that her actions threatened the retention of their old home. Notwithstanding, his wife begged him to finish the castle – but he was in no hurry to do so.

One day at dinner, the Tanist found his sight had almost completely failed him, and asked his wife to place before him a dish which he could not himself see. She answered disparagingly that even a blind man could see the things placed before him on a table.

‘Thank you madam,’ he replied curtly, ‘the completion of your castle will be when the blind can see.’

And so Bunaneer Castle was never completed.

The lands of the Chief and his Tanist at Ballycarnahan and Caherdanielmore were later confiscated and granted to Sir Thomas Roper, the governor of Castlemaine Castle.

As such, Ballycarnahan Castle also remained incomplete.[4]

The Battle of Bunaneer

The following account recalls events leading up to the Battle of Bunaneer from a manuscript history of Kerry.[6] It records how Daniel O’Sullivan More, who was married to Ellen Brown, enjoyed his estate but for a short time, for he joined Daniel M’Carthy, Terence O’Brien, and his two uncles in opposition to Cromwell.

Drumcasseragh

The first action was at Drumcasseragh where they were defeated and where all behaved themselves courageously and where one of the colonels acted such a brave part that his deeds were versified by a Kerry poet.[7]

Knocanoss

The next action was at Knocanoss where the Irish, after a most resolute contest, were defeated; after which there were several treaties for peace set on foot which came to no issue and consequently Knocnaclassi, by mutual consent, was fixed for the field of battle.[8]

Knocnaclassi

In this skirmish, Count Taafe, commander of the Irish, with his army was totally defeated. Soon after which battle, the aforesaid Daniel M’Carthy, Terence O’Brien and many others submitted to much more moderate conditions than they would before have got.

Daniel O’Sullivan More, who had lost a good many of his regiment and name, marched to that part of the county of Kerry called the baronies of Iverka, Dunkerrin, and Glanerough, expecting by the bad passes and roads thereunto leading, that he would maintain said districts till further supplied and relieved.

By this time the aforesaid two colonels, uncles to O’Sullivan More, seeing no further prospect of success, declined that service and went to France; and soon after the Earl of Inchiquin, having a tenderness and concern for O’Sullivan More, sent to him, earnestly desiring him to submit and that he would use his best endeavours with the government to get him good condition.

O’Sullivan, after returning his lordship thanks for his good inclinations, replied that if he had his estates and those of such of his countrymen who were with him granted, then he would submit, but not otherwise.

The said earl having made a report of this negotiation, it was not approved of but, on the contrary, commands were issued that O’Sullivan’s territory should be invaded by land and sea; and in order to bring O’Sullivan speedily to submission, a strong party of effective men was embarked on board of three or four ships from Tralee bay.

Ballinskelligs

O’Sullivan had at this time his little army at Glenbeagh, where late in the afternoon he was apprised that said ships, with a fair wind, were making sail towards the Skeligs. He immediately divided his party into two divisions: one headed by himself proceeded towards the harbour of Poulnanurragh, the other party comprising four companies under Captain Owen O’Sullivan of Fermoyle, an experienced officer, and commander of a regiment, marched towards Ballinskelligs.

The ships containing the invading troops came to anchor in said harbour early that night and sent out three companies of about one hundred and sixty men who surprised most of the inhabitants before day, took all the booty, and drove off all the cattle they could meet to the banks of the harbour.

By this time Captain O’Sullivan had arrived with his party near where the prey was collected, and observing the situation of the English, when resting after the fatigue of collecting their booty, and just preparing to take on board the cattle and the captures, O’Sullivan and his companies made four parties. He ordered Captain John Brennan with his company to take the advantage of a small valley eastwards of Ballinskelligs and attack the enemy, at the same time he would see him fall on. He likewise ordered another company under the command of Lieutenant M’Swiney to proceed along another valley westwards and with the same direction. He himself with a young captain, a namesake of his, the head of the family of Cossanalossy, with two companies marched towards the English who sounded their trumpets and made other demonstrations of joy at seeing them approach.

At the same time they took the advantage of fixing themselves behind a low ditch surround a small field on the brink of the sea which, O’Sullivan observing, he ordered what small arms he had in front of his party to be discharged as soon as well within musket-shot of the enemy and not to wait for charging again, or withstand the English firing, but to rush on and engage with pikes and broad-swords.

The Irish made the first fire which had no greater effect than wounding some few. The English had the patience not to fire even when their opponents were within musket-shot but when they began they made such smart and regular firing that it had the effect of killing seven or eight Irish and amongst the rest the young captain, the cousin of Daniel O’Sullivan, and many more wounded of which number was the captain commandant who, when shot in the thigh, and falling to the ground, the other captain, his namesake, made a motion of stooping to assist him but the courageous captain cried out not to mind him, for nothing had happened but the falling out of a button of his trowsers but to move on to the attack, and that he would be immediately after him.

The young officer dashed into the ditch and succeeded in dislodging the English who lost in this short dispute three or four men, but they withdrew in good order to the strand, the rear fighting and firing while the front were charging, but on their coming to the strand the aforesaid Captain Brennan came up with his division, and fell on furiously so that a most resolute and bloody fight ensued considering the numbers on each side, for Lieutenant M’Swiney did not come up until the action was over.

During this onset the English had not time to make further use of their muskets than to push with the bayonets that were fixed on them and the Irish worked away with their pikes and broad-swords at which they were active and expert so that the said three English companies were either killed or desperately wounded, except a few who begged for their lives, Captain Edward Volier [Vauclier] only excepted, who fought with admirable courage while he had any to stand along with him.[9]

At last, after receiving eighteen wounds which did not prove mortal, he ran into the sea and swam until meeting with the boats coming, too late, with some reinforcements, which took him on board where he behaved like a soldier and a man of honour for some of the English that remained on board, as well as the crews, intended to hang the prisoners they had taken the night before which Volier hindered, declaring that he and his party met with their wished-for enemies from whom they had fair play, and that innocent people should not suffer on that account.

The Irish had about thirty killed in the action and about as many wounded, amongst whom was their courageous commander, much lamented by his party, as he was unable to serve afterwards.

The field of battle and the strand ever since have gone by the name of the English Garden and Strand.

Bunaneer

The English government having got an account of this action, a fort was erected in the Island of Valentia in Iveralagh, and another at Nedeen, in Glanerough, which were furnished with strong English garrisons in order to suppress O’Sullivan.

Meantime the Earl of Inchiquin, as also Lord Kerry, and other true friends to O’Sullivan, used their best interest and best offices for peace and good conditions for him and thereby a cessation of arms was agreed on so that no hostilities on either side were committed for three years.

The overtures at last proved abortive as O’Sullivan had no other offers made him but some thousand acres, to which he would not agree, or for anything less than his estates and those of his adherents. Instead of which the governor of the county had strict orders to take all opportunities of invading his small district to which purpose Captain Gibbons, governor of Nedeen, furnishing himself as privately as possible with many boats, embarked with about two hundred men from his fort.

O’Sullivan being apprised of this invasion, collected his small party near Glenbeagh, and divided them into three divisions, one hundred led by himself towards Ballinaskelligs, another by an experienced officer towards Sneem, and three companies by Captain Owen O’Sullivan of Capananoss and Captain Brennan (who had been in the action at Ballinaskelligs) towards the harbour of Poulnanarragh.

Governor Gibbons landed in the night before him, and marched with nine-score men towards the river Curane. But, as most of the inhabitants had some notice of his landing, he did not meet with many of them but next morning, he drove all the cattle of the neighbourhood and took all the booty he could get carriage for to the banks of the harbour.

At which time the Irish party arrived at a hill above the fort near a church called Crocane whereupon the English shouted, and challenged for battle, and drew themselves up in three columns, one in number sixty, under the command of the governor forming the right, the same number under Lieutenant Boyne forming the left, and the remainder commanded by Ensign Bostyn formed the centre.

The Irish suited the same battle array, dividing themselves into three companies of about fifty each, commanded by Captain O’Sullivan on the right, Captain Brennan on the left and a subaltern officer of the O’Sullivan’s at the centre.

The Irish commander gave the same order that he did at Ballinaskelligs. Both parties with undaunted resolution marched in the aforesaid order until they met at a field near the Castle of Bunanire called Droumfaddy at the back of said harbour where what happened was remarkable.

As the six officers marched on with such resolution, and at some distance in front of their men, the first firing took place which did not hurt any of these officers, and then they engaged hand-to-hand when Lieutenant Boyne fell by the hand of Captain O’Sullivan, Governor Gibbons by the hand of Captain Brennan, and Ensign Bostyn by that of the subaltern officer.

This in some measure discouraged the English party yet they fought very well for some time, but as the Irish had the advantage of pikes and broad-swords, and were expert at the use of them, the English were put into such disorder as occasioned their entire destruction so that not one out of the nine score escaped being either killed or wounded, and but very few prayed for quarter.

The wounded were treated most tenderly as prisoners until an opportunity occurred for exchanging them. The Irish lost about twenty, killed in the action, and the same number wounded. This was called the fight of Bunanire, from the adjoining castle; by others it was called Droumfaddy, from the field.[10]

____________________

[1] The following description is taken from Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Letters: ‘Situated in the townland of Ballycarnaghan [Ballycarnahan, Ballycarney] in this parish [Kilcrohane] is a small portion of the ruins of a square castle situated on a rock. It measures on the outside 36.6ft from east to north and 28ft from north to south and its walls are 5ft thick built of green-stone grouted but now not more than 20ft high. The doorway was on the east side but is now entirely destroyed and the staircase which was a spiral one led to the top in the north east corner. All its windows are now destroyed. There is no tradition of the founder or occupier of this castle but there can be little doubt that it was built by O’Sullivan More.’ Donovan also notes the following in the parish of Prior: 'In an account of Kerry written about the year 1750, preserved in the library of the Royal Irish Academy in the O'Gorman Collection we find in the enumeration of the families that had estates out of O'Sullivan More's house in the county of Desmond the family of Formoyl and Ballycarna, mentioned the 8th in number of these families. The words are: '8thly the family of Formoyl and Ballycarna likewise ref'd to said records (O'Sullivan More's) what other denominations they had besides the four plowlands of said Formoyl and the four plowlands of said Ballycarna. They built the Castle of Formoyl and began the Castle of Ballycarna a little before Cromwell's time which they did not finish; they were a family of good note for generosity, manhood and education. Of the family of Formoyl was the courageous Captain Owen O'Sullivan who was wounded and disabled in the skirmish of Ballinskellig (for this skirmish see MS p93 and see Smith's History p104) of which there will be a further account given in the following discourse, speaking of Cromwell's wars, Daniel Garane O'Sullivan of the branch of Ballycarna, an officer of good note in said wars, and afterwards in France and for learning and poetry.’ ‘Of this family of Ballycarna was a young man that went abroad in the late Queen Anne’s wars to South America where he fixed himself in the town of Potosi in Peru where he acquired great riches of which he made a remittance to his friends of seven hundred pounds and at another time a remittance of fifteen hundred pounds and intended, as he wrote, to put in very considerable sums into some banks in Europe but was taken ill and died before he accomplished his intent, and it is not known to whom he left his last will, or nominated his executors; but it is expected that a worthy clergyman, the Rev Dr Mortough O’Sullivan, who lately came from said country of South America to Cadiz in Spain can give an account hereof (1755). Ref: King’s History of Kerry, ‘The O’Sullivan Family’ Vol VI. Diermod McDaniell O’Suollyvane [O’Sullivan] lived at Ffermoile, 12th October 1629. Captain Dermot O’Sullivan of Fermoyle did good service for Charles II and is specially named for favour. Theobald Magee was the son of the ‘Long Sword Captain’ by this time famous in song and story, who married the widow of Thomas Morgell and the sister of Sir Maurice Crosbie. She lived to be the Captain’s widow too. The ‘Kerry Pastoral,’ a dialogue between Murrogh O’Connor of Augnaghraun and Owen O’Sullivan of Reencarran gives the history of the wrongs inflicted on the latter by the Magees: ‘But shall this foreign Captain force from me/My house and lands, my weir and fishery;/Was it for him I these improvements made –/must his long sword turn out my labouring spade?’ queries poor Owen plaintively and to little purpose for the foreigner, as Magee was called in Kerry, prevailed and his son, Theobald the conformist of 1725 died, holding a long lease of Reencaragh, Portmagee, Aghatubrid, Doon, Rahirrane and part of Valentia which he bequeathed to his nephew, David Lander. The conformist also held lands in Cork and Ballymore and Ballyoughteragh near Dingle. In his will, dated 7th September 1745, proved in December of the same year, he bequeaths his interest in Ballymore to Eliza Hussey’s son, adding, ‘I doe recommend that he be bred a Protestante.’ His mother seems to have been like all her family (in Kerry at least) a Protestant; but in the very year he and his brother George above mentioned conformed, their father died in the city of Lisbon a devoted Romanist. In his will he directs his body shall be buried in the Irish Dominican Convent in Lisbon and leaves money for high and low masses to be said to his soul. He mentions his beloved wife, Bridget Magee, otherwise Crosbie, and directs that his children ‘shall not be altered from the Roman Catholic religion’ in which he says he had them ‘brought up.’ Neither George nor Theobald Magee left any issue and the family is long extinct in the female line (From King’s History of Kerry, ‘The O’Sullivan Family’ Vol VI). The following description of Fermoyle Castle is from Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Letters (parish of Prior): ‘In the townland of Fermoyle in this parish, are some remains of an old castle, situated at the foot of Fermoyle (Formaoil) mountain and at the south side. It was built of green stone and lime and sand mortar, the work was grouted. Length of the castle from east to west was 27 feet and from north to south 25 feet 4 inches on the inside as well as could be ascertained now by means of the foundations of the walls. Thickness of the walls was 6 feet 3 inches. The south west angle to a height of about 11 feet on the interior and 18 or 20 feet on the exterior, remains, formed by 5 feet in length of south wall, and 4 feet 3 inches in length of west wall. The foundations of north east and west walls are traceable. The south wall still retains 10 feet in height on the exterior even the lowest part. At the south east corner is an apartment with a stone roof, which is said to have been the guard room, placed at south side of the doorway which was on east wall of the castle, and on one side of which a staircase ascended to the top of the building. Height of this apartment is 9 feet 4 inches. It measures from north to south 8 feet 11 inches, and from east to west is 7 feet 10 inches.Thickness of east wall is 3 feet 8 inches, of west wall 2 feet, and of north wall 1 foot 10 inches. There is a breach on north wall at west wall north east angle is battered outside. There is a little square window on east wall battered outside … Ballycarna (baile na cearnacain) is now Ballycarney townland in the parish of Kilcrohan.’ See The McGillycuddy Papers (1867) edited by W Maziere Brady, DD, for various transcripts of early seventeenth century letters and legal documentation which includes the O’Sullivans. The Kerry Pastoral referred to by Jeremiah King above and given below is from a version in the Dublin University Magazine (1861), Vol LVIII, July to December, introduced as follows: ‘Considerable tracts in the county of Kerry were granted to Trinity College about the middle of the seventeenth century. But as the learned proprietors took more interest in the pleasant fields of literature than the rocks and heaths of that wild county, their possessions were mismanaged by middlemen, and gross instances of tyranny occurred. Things were not improved by the Jacobite wars. A nameless scholar of the early part of last century [18th] endeavoured to enlist the sympathies of the Fellows by the following imitation of the first eclogue of Virgil. It is from a copy supposed to be unique, presented by Sir William Betham to Thomas Crofton Croker, and was published by the Percy Society. The whole piece is replete with allusions to the modes of life prevalent in the kingdom of Kerry 150 years ago [c1710].’ The verse had in fact been published earlier, under title, ‘A Pastoral, In Imitation of the First Eclogue of Virgil: Inscribed to the Provost, Fellows, and Scholars, of Trinity College, Dublin by Murroghoh O Connor of Aughanagraun’ in Miscellaneous Poems, Original and Translated, by Several Hands (1724) pp308-319, introduced as follows: ‘Murroghoh O Connor and Owen Sullivan. The Argument. Murroghoh Mc Tigue, Mc Mahoon Leagh, Mc Murroghoh O Connor, of Aughanagraun, in the Barony of Iraghty Connor, and County of Kerry, was among other College Tenants turned out of his farm at Ballyline, but being recommended to the college by several gentlemen of that country is restored; in this Eclogue, therefore, he owns his obligations to the college, and the happiness of his condition. Owen Sullivan of Rhincarah [Reencaheragh], near the Island of Valentia, in the Barony of Ivrahagh (another College Under-Tenant) meeting with some misfortunes, and not having represented his case to the college, loses his farm, which is given to a Captain of that Country.’ See also ‘An Eclogue in Imitation of the first Eclogue of Virgil,’ Verse in English from Eighteenth-Century Ireland (1998) edited by Andrew Carpenter, pp83-89 with notes. Morrough O’Connor flourished 1719-40. Murroghoh To her (Trinity College) I owe the happiness you see; ’Twas she restored my farm and liberty, For which full mathers to her health we’ll drink, And to the bottom stranded hogsheads sink – Good stranded claret wrecked upon our shore, And when that’s out, we’ll go in search for more.’ Owen When all these omens met at once, I knew What sad misfortune must of course ensue. But tell me, Murrogh, what the College is: There’s nothing more I long to know than this. Murroghoh Owen, I was so foolish once, I own, To think it like our little school in town, Or like the school that’s in Tralee, you know, Where we to ‘sizes and to sessions goe, And when arrested, stand each other’s bail, And spend a cow or two in law and ale. I might compare Drumcon to Knockamore, Curragh of Ballyline to Lissamore With much more reason, but my dearest friend, The College does our schools so far transcend, Or all the schools that ever yet I saw, As Karny’s cabin is below Lixnaw. Owen But what good fortune led you to that place? Murroghoh To tell my sufferings, and explain my case, ’Tis true I lost my landlord’s favour by ‘t, But then, dear Owen, I regained my right, All my renewal fines with him were vain, Nor pray’r nor money could my farm obtain. What could I do but to the College run? And well I did, or I should be undone. There did I see a venerable board – Provost and Fellows, men that kept their word. They soon (for Justice here knows no delay), Gave this short answer, ‘Murrogh, go your way: Return, improve your farm as before; Begone, you shall not be molested more.’ Owen Thrice happy you! who, living at your ease, Have nought to do but see your cattle graze, Speak Latin to the stranger passing by, And on a shambrog bank reclining lie; Or on the grassy sod cut points to play Backgammon, and delude the livelong day. Murroghoh Sooner shall Kerry men quit cards and dice, Dogs be pursued by hares, and cats by mice, Water begin to burn, and fire to wet, Before I shall my College friends forget. Owen But I must quit my dear Ivragh, and roam The world about to find another home, To Paris go with satchel crammed with books, With empty pockets and with hungry looks; Or else to Dublin to Tim Sullivan, To be a drawer or a waiting man; Or else perhaps, some favourable chance By box and dice my fortune may advance. But shall this foreign Captain force from me My house, my land, my weirs, my fishery? Was it for him, I these improvements made? Must his long sword turn out my lab’ring spade? Adieu, my dear abode! Murroghoh But stay, dear Owen! Cosher here this night. Behold the rooks have now begun their flight; The sheep and lambkins all around us bleat; The sun’s just down; to travel is too late. Slaecan and scollops shall adorn my board, - Fit entertainment for a Kerry lord; In egg-shells then we’ll take our parting cup, Lie down on rushes – with the sun get up. [2] The following from King’s History: O’Sullivan territory was directly subject to O’Sullivan Mor of Dunkerron and Dunloe Castles, whose overlord was MacCarthy Mor of Castle Lough, Pallis and Ballycarbery. The nine branches of the O’Sullivans are: 1. MacGillicuddy 2. O’Sullivan Cumurhagh or Mac Muirrihirtigg 3. O’Sullivan of Glenbeigh 4. O’Sullivan of Caneah and Glanacrane 5. O’Sullivan of Culemagort 6. O’Sullivan of Cappanacuss 7. O’Sullivan of Capiganine 8. O’Sullivan of Fermoyle and Ballycarna 9. O’Sullivan of Ballyvicillaneulan. [3] Bunaneer/Buninire, otherwise Castle Cove, Castlecove, Cuas an Chaisleain, Caisleán Bhun Inbhir. The following description of Bunaneer Castle is taken from Donovan’s Ordnance Survey Letters: ‘At Castle Cove in the south of this parish is a part of the ruins of another castle situated on a rock and called in Irish Caislean Bona an Uidhir ie the Castle of the mouth of the River Ire or Eir. It measures on the outside 38ft 4in from north to south and 21ft from east to west and its walls are 5ft in thickness and now about 16ft in height and built of (what the country people call) green stones well grouted. A spiral staircase led to the top at the north-west corner. Five windows remain perfect and formed, as usual, of cut stone; two pointed ones on the north wall, two on the east wall, of which one is round-headed and the other rectangular and one on the south wall, round-headed. There is a square entrance on the west side to the left of which is the staircase and a semi-circular headed doorway formed of cut stone admitting from the first returns of the stairs to the second floor. This was also one of O’Sullivan More’s castles.’ The following is taken from King’s History of Kerry, published in the Kerry Evening Post, 28 September 1912. ‘Bunaneer, or Castle Cove, a square unfinished castle, close to the shore of the Kenmare River. It does not differ from the ordinary types of castles or tower houses of the sixteenth century except in having a kind of string course which is formed of thin flag stones in the shape of a reversed V, and like the weather mould of a gable on each face. Below this the walls batter, above they are vertical, consequently the string has hardly any ejection at the angles of the tower, but a considerable one at the apex of the V, or gable-like figure. In a field about a mile and a half NE of Bunaneer there are the ruins of what appears to be an old house. It is a parallelogram with a door in the centre of each of the long [?] and several windows, all of rubble rock. The doors had pointed arches. Internally the walls have [?] grooves as if for timbers. Smith says the roof came down to the ground and thus explains these grooves.’ Castlecove Castle: Record of Protected Structures, Behaghane/Behagane KE107-007. The ruin was up for sale for 150,000 euro in 2014. [4] Above account taken from ‘Tales and Traditions of the County of Desmond.,’ The Liberator, 22 June 1935, Text in full: ‘In the disturbed days of Elizabeth’s reign, the O’Sullivans of Bordoinin decided to build a castle at Ballycarna, their chief residence in the district. This was done for protection and security. They were obliged to take their part in the wars against the queen. The tanist of O’Sullivan of Ballycarna had his home at Lisstyconchubhair, the liss of Connor’s house, now known as Liss. In fact the ruins of the old house are still extant. While both were away at the wars the tanist’s wife considered herself a superior lady to the wife of the head of the house so she set about building a castle for herself, at Bunaneer, on the water’s edge and had raised the walls as they now stand, when the husband returned from the war almost totally blinded, the result of a sever attack from an enemy. When he heard of what his lady had done during his absence, he was very vexed with her, and told her it was very possible she may be unable to retain her old home in the strenuous days to come, and he was in no hurry to finish the work in spite of the importunities of the wife. One day at dinner he found himself totally blind, and had to ask his wife to place before him something he required and which he could not see. She answered very unsympathetically that even a blind man could see the things placed before him on the table. ‘Thank you madam’ he replied, ‘the completion of your castle will be when the blind can see.’ It was never completed. We may add that his prophecy about retaining her old home came true, as the lands of both chief and tanist were confiscated, the lands of Ballycarnahan and Caherdanielmore being granted to Sir Thomas Roper, the governor of Castlemaine Castle. The Bunaneer Castle and lands remained in possession of the owners till sold, as the following from the Macgillicuddy Papers shows: ‘On the 28th February 1623, Tadg MacFignin O’Sullivan gave over to Conor O’Sullivan alias MacGillicuddy, possession right etc to Bunaneer Castle and one ploughland, called Fearan na Tragha, in the town and lands of Behehane, the property of Tadg.’ They finally became confiscated by the Cromwellians. Some came to Bland and more to Carbery, who, I suppose, bought them up from the soldiers to whom they were allotted.’ [5] The ruins of two castles at Ballinskelligs are indicated on the 19th century Ordnance Survey maps, one near the abbey, and the other near Ballinskelligs Point. Names associated with their history are McCarthy, Harding, Segerson, Marshall and Petty. Donovan, in a detailed account of the Ancient Hamlet at Ballinskelligs in his Ordnance Survey Letters (parish of Prior), provides descriptions of both castles. The first, ‘to the west of the pothrach’ is named as ‘Caislean beg, little castle.’ The second ruin near Ballinskelligs Point is described as follows: ‘Situated on the extremity of a narrow ridge of land running a considerable distance north eastwards into the bay is a castle in ruins about /4 mile to the north east of the abbey. It is built of green stone and lime and sand mortar and the work is grouted. The length from east to west is 33 feet 4 inches outside and from north to south 25 feet 8 inches same side. The present height 18 feet 5 inches taken at highest part of the south wall. Thickness of the walls is 6 feet 6 inches. The doorway is placed on south wall, constructed of cut stone and pointed. Height is 4 feet 5 inches, breadth is 4 feet 2 inches. To left as one enters was the staircase which at 1st return ascended spirally on south west corner rounded inside in form of a tower, and also at the 1st return had a branch from it, running along south wall eastwards. The inside of the tower is destroyed. Its outside and a portion of the west wall at north side rise 8 feet higher than the rest of the castle to the right as one enters on the doorway, is a little apartment called Seampa an Boduig which signifies the Chamber of the Rustic. The entrance to the ground floor inside the door is square and constructed of rude stone being crossed by a stone cut top. It is very low now. It appears the castle had but two floors in it. On south wall is a square opening above doorway which is a window place, above which was a narrow window now broken. There is another opening on this wall opposite the staircase. It is also battered. There is a narrow window above it. On east wall is a square window at ground, battered outside. Above it is another, and at now top is a small one broken in upper part. There is one cut stone in the north side of the uppermost, and no cut stone in the others. The quoin stones are cut. The north east corner outside is battered below. The north wall has 2 openings, one narrow and square at the ground, the other large and square, placed in the middle of the wall. Above it was a narrow window now broken. They were all constructed of rude stone. The quoins are out of the north west angle to near top. There is one small square opening on west wall near south west angle. There was a large square opening at the now top. It is broken in the upper part. The quoins are out of south west angle more than halfway up. Smith in his History of Kerry (p103) speaks of Ballinaskeligs abbey and castle in these words. ‘At Ballinaskeligs are the ruins of an ancient abbey or friery of the order of Augustine Canons; it was formerly removed hither from the island called the Great Skelig where it was a monastery consisting of several cells dedicated to St Michael the Archangel, the time of its foundation is not known but it must have been of great antiquity, probably as early as the sixth century. The annals of the abbey of Inisfallen, in Lough Lane, in this county, say that Flan Mac Callach, abbot of Skelig, died in the year 885. At what time the monks quitted the island is uncertain, but by the large traces of ruined buildings which the sea is continually demolishing, it appears that this abbey had been formerly a very large edifice, it was granted, upon the dissolution of religious houses, with its possessions to one Richard Harding. There are some traces of a town still remaining besides a small castle, built formerly on an isthmus to defend the harbour against pirates who had done considerable mischief hereabouts.’ The ruins of a large house formerly occupied by a man named Segerson are still seen here. There are also the ruins of his tenants houses. Segerson is mentioned in Smith’s history (p104). In the Annals of Inisfallen at AD 1272 it is stated that ‘The castles of Roscommon and Sceilg together with many others were taken from the English and demolished.’ In a tribute to Dr George Sigerson (1836-1925), who is described as ‘the last male of the family,’ it is learned that the family ‘seems to have sprung into prominence in Elizabethan times, one member, Ralph Sigerson, was the honoured Mayor of Liverpool and advanced large sums for the purpose of Irish government. A branch of the family migrated to a distant promontory of Kerry and settled harmoniously among the people. The ruins of the Castle are standing today at Ballinskelligs, and the traditions and folklore of the family still linger in the neighbourhood. Another member, Roger Sigerson, married the widow of Edmond Spencer, the poet, whose maiden name was Elizabeth Boyle, cousin of the 1st Earl of Cork … Dr Sigerson has published several treatises on nervous diseases … In his student days as far back as 1860 under the nom-de-plume of Erionnach he published The Poets and Poetry of Munster’ (Saturday Herald, 1 March 1913). In a detailed note on the Segerson/Sigerson family (Last Colonel of the Irish Brigade (1892) by Mrs Morgan John O’Connell, pp206-211), their connection to Kerry is given in more detail: ‘The Kerry branch obtained their possessions in a romantic manner. Richard Harding, of a great Bristol family, had obtained large grants of land in several counties of Munster and Leinster, after the confiscation of the Earl of Desmond's estates. He made over the reversion of his manor at Ballinskelligs to Christopher Segerson in 1615. The tradition is that, having made acquaintance with the young knight in Ireland, the latter became a favourite, and was taken over to Bristol that he might marry Harding's daughter. As they were about to enter his home they met her funeral coming out of the door. Richard Harding still treated him as his son-in-law, and gave him the manor. Christopher Segerson was one of the sons of John of Wexford and Dublin City. He became lord of the manor, with rights of warren and chase, enjoyment of waifs and strays, powers to hold courts baron and leet, markets and fairs, and a ‘court of pie-powder,’ in about the year 1636, and the estate was confirmed to him by royal grant in 1637 (Charles I). The property comprised ‘the late priory and house of Fryers of Ballyneskilleg’ with ‘the townes and lands of Ballyneskilleg, Kinard, Ballintemple, Argyll,Kinnagh, Cloghanemore, Dungegan, Killurley, Coolagh, Imlaghmore, Cashell, Tuoroglassoge, and Kildonan.’ At this time Christopher Segerson held a half-moiety of Cloghran-Swords, in Dublin County. He ran risk of losing his life, having been lawlessly seized ‘as hostage’ by some of Sir W Denny’s marauders, who burned the village, but they were compelled to give him up owing to the success of O’Sullivan Mor’s forces. Less fortunate, a few years later, all his Kerry property was confiscated under the Cromwellian Government. In 1653 transplantation certificates were made out for Christopher Segerson of Valentius, and Richard Segerson of Ballinskellix. In the ‘Book of Survey and Distribution’ the details of the estate are set forth; it covered about 7500 acres of present measurement. Two castles are mentioned. The original grantee was Robert Marshall, but the property quickly passed to Sir W Petty, surveyor-general, who thus built up the fortunes of his family. By the Commission of Grace, Christopher got back some of his Dublin possessions. In 1696 Henry Petty (Earl of Shelborne) made a lease in trust to his agent, for John Mahony, of Dunloe, who immediately re-leased the estate in 1697 to Christopher’s heir, Thomas Segerson … They intermarried with the principal old families of the county, eg, Mahony, Conway, O’Connell, McCarthy, O’Sullivan, Sugrue, Spotswood, Leyne, Lalor, Blennerhassett, Hoare, FitzMaurice Burke. There are several alliances with the O’Connells. Alison, or Alice, daughter of the first lord of the manor (Christopher of Dublin) married Daniel O’Connell of Aghort and Darrynane. She was consequently great-grandmother to General Count O’Connell and great-great-grandmother to the Liberator who thus had Norse blood blended with Celtic in his veins … John Segerson, of Drumfadder and West Cove, bequeathed (1825) the Ballinskelligs property to his daughter, Lucinda Catherine, mother of the present Richard Mahony Esq, DL, Dromore Castle, Kenmare whose children are Harold Segerson Mahony and Nora Eveleen Segerson Mahony …’ In the twentieth century, the castle was purchased by Tim O’Shea of Cahersiveen. An obituary to ‘Tadhg’ O’Shea (Kerryman, 12 August 1988) states, ‘By amassing a huge collection of the genealogy of his beloved Uibh Rathach and by buying the McCarthy Castle at Baile na Sceilg for preservation (where various artefacts of consequence have already been discovered) he was assuring the community that their past would be retained for posterity.’ The following is of interest: ‘A Ballinskelligs castle offered to Kerry County Council as a gift should be hit by a scud, Councillor P J Cronin declared this week. ‘What should be landed in the middle of that castle is a scud,’ Councillor Cronin said, ‘it was built by the penny-a-day Irish.’ Councillor Mick Gleeson observed the council was full of patriots. Council Chairman John O’Donoghue had recommended that the council accept McCarthy’s Castle at Ballinskelligs as a gift of the O’Shea family. Councillor O’Donoghue said the castle was a landmark on Ballinskelligs Beach and under threat from the sea. Council Secretary John Deasy said they had no communication from the O’Shea family and proposed the family write in and that the county engineer make out a report’ (Kerryman, 15 March 1991). [6] ‘Extract from a MS. History of the County of Kerry, in the Library of the Royal Irish Academy’ published as an appendix in Sketches in Ireland: Descriptive of Interesting Portions of the Counties of Donegal, Cork and Kerry (1839) by Caesar Otway (first edition published in 1827 from Otway’s excursion of 1822; second edition published 1839), co-founder of The Christian Examiner and Church of Ireland Magazine and Dublin Penny Journal. The ‘MS History of the County of Kerry’ is attributed to Friar O’Sullivan OFS of Dunkerron. It was edited by Father Jarlath Prendergast of Killarney Friary, author of Muckross Abbey A History, and published under title ‘Ancient History of the Kingdom of Kerry by Friar O’Sullivan of Muckross Abbey’ in the Journal of the Cork Archaeological Society. It appeared in series form from 1898-1900. The preface to the first part (Vol 4 No 38 (1898) pp115-131) contains Fr Prendergast’s discourse on the identity of Friar O’Sullivan, though Fr Prendergast ultimately concludes, from the style of the language, that the document may be sixteenth rather than eighteenth century and ‘it must have been written by a lay member of the community, like O’Clery, the chief compiler of The Four Masters, and not by a priest.’ The following is taken from Muckross Abbey A History (2018) pp133-134. ‘Cromwellians under Captain Vauclier, sent by Denny from Tralee, led three companies and was opposed by Captain Owen O’Sullivan of Formoyle. The attack was led by Captain Owen, who was wounded in the thigh and the leadership fell to Owen O’Sullivan, head of the Cappanacoss family. The next in command, seeing his leader fall, he paused to give aid but the latter called on him to go on, as only his braces had given way, thus preventing any check being given to the onset of his own party. The English were annihilated; Captain Vauclier saved himself by swimming to the boats, though he had a pike sticking in his back. Irish loss – 30 killed and more than that number wounded. Captain Gibbons with 200 men left Neddeen fort and landed at Paulnanarah [Poulnanarragh]. At Crocain Church they were both attacked by the Irish 150 strong. Both sides were divided into three columns and the leaders outstripped their followers in the onset and then engaged in single combat, viz, Captain Owen O’Sullivan of Cappanacoss, Irish leader, against Governor Gibbons, the English leader, and Subultern Officer Sullivan, against Ensign Bostion. In each case the English officers fell and not one of the English party escaped death or serious wounds except a few to whom quarter was given. Irish loss – 20 killed and about the same number wounded. This is called the action of Buninire, or Droumfadda.’ [7] ‘In which he argues the equality of his hero with Owen Roe O’Neil whose fame was exalted by a Northern poet. In this poetic contest the northern rhymer says that O’Neil was the hand and thumb of Ireland. The Kerry poet asserts that the hand should be divided between the two champions, so equal was their merit.’ [8] ‘A circumstance that happened the night before the engagement is not altogether pertinent to the purpose of this story yet I shall set it forth. The Earl of Inchiquin, who was general of Cromwell’s army, hearing of a wizard or man inspired by prophecy being in the neighbourhood, sent for him and desired to have his opinion as to who would gain the victory on the following day. On this occasion the gifted man was much daunted which the earl observing, desired his freely to express his thoughts, and that whatever he should declare, he should not be in the least molested. On which the man pronounced that the Irish would maintain the field with credit but that the English would be totally defeated. Whereupon the earl answered that he was right for that he was an Irishman, an O’Brien, and therefore a Milesian; but that Count Taafe, the commander of the Irish, was an Englishman by extraction. The event was as the earl had interpreted; for Taafe, with his army, after a desperate struggle, was totally defeated.’ [9] The following note appears in Miscellanea Genealgica et Heraldica (1881) Vol III: ‘Lucius Denny died unmarried. His godmother, Mrs Vauclier, was the wife of a Captain Edward Vauclier, an officer of Huguenot descent, serving in the English army in Ireland, who had settled in Kerry. His deposition, detailing his sufferings and losses in 1611-2 at the hands of "Walter Hussey of Castle Gregory, O'Sullivan More of Dunkerron, Florence MacCarthy, Esquires, Daniel MacMoriarty, Garret Fitz James Gerald, Christopher Hickson of Knockglass, gentlemen," and other " Papists and rebels " (as he styles them), is in Trinity College Library, Dublin.’ The following is taken from the ‘Deposition of Edward Vauclier’ (MS 828 fols 284r-285v) dated 21 March 1643 held in Trinity College Library, Dublin: ‘Also he sayth that Arthur Barham of Clougher Brine gentleman Robert Brooks of Carriginyfeily gentleman Robert Lentall of Treley gentleman Tho: Arnold of the same gentleman John Cade of the same gentleman Griffin ffloyde of kilarney gentleman William Wilson of the same Dyer Donnell O Conner of kilarney maulster Robert Warrham of Treley gentleman John Godolphin of Treley shoomaker Hugh Roe of the same Barber Beniamin Weedin of the same Hosyer Honry knight Taylor Richard Hore of the Newmannor husbandman, & diuers others protestants to the number of fourty were all treacherously killd & murdred by O Sulliuane More of Dunkerrin aforesaid Esquire & his followers to the number of six or seuin hundred rebells, the deponent hauing the comand of the said protestants there being two more that escapt: & the deponent sau’d his life by Leaping off a rock into the sea being enforct to swime at Least a mile & so gott away hauing first receiued fourteene wounds with swords & Skeins & one shott in the right shoulder & one doope wound in the back with a pike, this was don about midsommer Last 1642, nere Ballynoskellicks in said com (https://1641.tcd.ie/index.php/deposition/?depID=828284r362). [10] The extract concludes as follows: ‘The account of it exasperated the government so much that a proclamation was issued that all persons met without a protection at the south side of the river Lane, or westward of the Finhih near Nedeen fort, were to expect death without mercy and all goods taken at the outside of said line to be forfeited without redemption which daunted the poor inhabitants so far that a great many families out of Ivrah, Bordonine and Glencarn met at Glencarn with an intent to go over the river Lane for their safety; who had the hard fate of meeting with a strong party sent out by Brigadier Neilson, governor of the county, as well as of Ross Castle, at a mountain called Reana-larane, said party being commanded by Captain Barrington, a blood-thirsty man, who on this occasion spared neither man, woman or child. Some few young men by their great activity were making their escape until Barrington set on a bloodhound he had with him, of a large size and swiftness, who overtook and tore many of them. Soon after, several poor families of Bordonine, Ballybeg &c &c employed a friend who was under the protection of the governor of Nedeen to procure a pass for them from him; this pass was promised should be given them on a certain day if they repaired at that time to the river Sneem, to which place they went with their cattle &c &c and then not meeting with the said pass, in was their dire fate to meet with Captain Barrington at a large mountain in Ballybeg that to this day goes by the name of Slieve na Vorihih – the Mountain of Slaughter. Neither man, woman or child were there spared and those who endeavoured to make their escape were torn by his bloodhound, one young man excepted who, by his great activity in running, made his way towards a hill called Sanavame a good distance from the mountain. Barrington’s men pursued him and unable to come up with him, set the bloodhound on him which the youth perceiving prepared himself by slipping off his waistcoat, and wrapping it round his left arm and wrist, he then drew his broad-sword and, as the brute was rushing on him with great fury, its first attempt at tearing him, he parried with his left hand, and with the right he gave it such a manly stroke that he cut off the two fore feet. His name (as near as I could learn) was Brennan; whoever he was he had great thanks, praise, and prayers for destroying the merciless beast which never is forgot in the country; some to this day, when they meet with cruel dealings or bad neighbours, are apt to say, they would as soon trust Barrington’s bloodhound as them. A short time after said slaughter, some poor inhabitants of Ballybeg were obliged to withdraw to Iveragh, Bordonine &c &c and, as they left some sowings behind them in Ballybeg, they, next harvest, attempted to come and cut, and bring away the sowings, and to that intent removed their families along with them, and had out sentinels by day but by night went to shelter themselves in the adjoining woods. This being discovered by the garrison at Nedeen, a party was sent out in boats by night, the most of them being of Captain Purefoy’s company, who surprised said colonies in a wood called Easgah in Derequin. None were spared except a few women and children and some of them were most inhumanely dealt with. Next day, as a sucking babe would have been thrown out of a boat on the waves, and when the mother at that sight did grieve, she had her breast cut off with a hanger. But notwithstanding this surprise, as provisions were so extremely wanting to the rest of the poor inhabitants, a number of active young men attempted to carry off these sowings but not being fully prepared, were obliged towards night to lodge in the woods and coppices of Dunquinally, and in Ballybeg, where they were likewise surprised by said party, especially some young, unmarried men who went by themselves to the coppices of a small Inch, in said place, where they were all killed. This Inch is ever since called Inchnanaoganagh signifying the Inch where the young men were slain. About this time the governors of Ross, Nedeen and Killorglen &c &c &c used all efforts to make incursions into O’Sullivan’s country upon which he was obliged to divide his small army into different parties to secure the different passes of Drung, Knocnagaintih, Ballaghbawn, &c &c a party whereof under the command of Captain Owen O’Sullivan and Brennan were stationed from the hill of Knocnagaintih to the harbour of Poulnarnarragh and the river Curane, and they gradually came to the camp at night in the centre of said station. But as the aforesaid garrison always employed numerous spies by whose means they were informed of the strength and position of the Irish army; therefore, a powerful party marched in the beginning of a night from Killorglen, who met with some of these spies by the way who informed them that the Irish party came to camp late that evening at a place called Glenmore to which the English were guided, who before daybreak surprised the Irish asleep in their huts and killed a good many before they could form a body or recover their arms, and such as escaped their fury took refuge in an adjacent wood; whereof was Captain Owen O’Sullivan, who having rode far that evening, before coming to the camp, lay in his boots and clothes all night; he directing his course towards a large mountain, was soon overtaken by a small party of about four or five men. The first that came up to him was a county Kerry Irishman who spoke to him and desired him to accept of quarter and deliver up his sword and purse which he promised to secure for him, and deliver him up safe to Captain Hassett, the commander of the English party. O’Sullivan replied he was glad to meet with a friend, making him so kind an offer, and to know that Captain Hassett was the officer commanding; he accordingly delivered up his sword and purse which the other men immediately challenged to be distributed as common booty; this the Irishman refused, thereupon the others fell on and cut Captain O’Sullivan to pieces to the great concern of Captain Hassett, as he was acquainted with him on occasion of the former treaties and meetings for peace, and was thankful to him for his tenderness to some English prisoners. Many besides Captain O’Sullivan, who carried arms, lost their lives on that day; amongst others was an ancient, decrepid gentleman, Mr Owen O’Sullivan of the family of Ballycarna, who was met with in his devotions in a den or hut in one of the neighbouring mountains. All the cattle of the neighbourhood were driven to Killorglen; this very much terrified the rest of the inhabitants of Iveragh and Bordonine so that they took all opportunity of procuring passes and protections, and by getting away by night, to come to the aforesaid lines of the Lane and Finihih. By this the districts of Iveragh and Bordonine were much straitened for provision and food was wanting for O’Sullivan’s little army in which situation he thought it necessary to force some cattle from under the protection of Nedeen Castle, and to that intent he marched by night through Ballybeg and the parish of Templenoe and arrived next morning at the river Finihih very near said garrison. On passing said river, the powder which was intended to be distributed amongst his men on arrival at the other side was put in the care of a man on horseback who dropt it into the water to the great surprise and disappointment of O’Sullivan who, farther, on directing that all carrying fire-locks should examine their charges and priming, found them to be damp and this gave room, when coupled with the dropping of the powder into the river, to suspect treachery. But there was not sufficient leisure to examine farther into the matter for a party of horse and foot marched out of Nedeen Castle; the horse engaged first, and reserved their fire until they came within pistol-shot of the Irish as if dreading no fire from them, and then discharging both their carabines and pistols at once and which, while making great execution, could not be returned by the Irish, who attempted to engage with pike and sword but the English gave way for the foot to engage, who discharged their fire-arms by platoons, retiring, after firing, behind their companions. O’Sullivan now concluded that his best plan was to repass the river which his troops did in tolerable order, but still attacked in the rear, until they came to a field called Gortnadrishanig above Dunkerrin Castle where they were so vigorously attacked by the English horse who still gave them disappointments by filing off as formerly when the Irish attempted to attack with pikes and swords so that, at last, they were put to entire disorder, retreating in small parties, by different ways, which the English suited by also dividing into small parties. A person was observed retreating, who wore a scarlet waistcoat, attended by two young men. This person the English took to be the O’Sullivan More and they were not mistaken, for it was he, along with two subaltern officers, brothers to Captain Brennan and Owen O’Sullivan. They were now closely pursued by three troopers who shot one of the young officers in the leg who, when attempting to rise again, had his head cloven in two. O’Sullivan now faced about, but he had no weapon but a small sword. The troopers now fired and the other young officer was shot and fell. Two troopers here dismounted to rifle him but one William Maher pursued O’Sullivan, fired at him, and missed; he then attempted to cut him down with his broad-sword but O’Sullivan being very active and expert parried his strokes and taking advantage of some bad steps in the rough ground, he kept the fellow in play for some time; but the desperate and unequal struggle was about closing when God’s providence put it into O’Sullivan’s head to throw off his waistcoat and cry out, ‘All I have is in the pockets, and there’s enough to make you rich all your life.’ Maher, tempted by the booty, and seeing the other two troopers coming up, and craving to have all, alighted to seize the waistcoat and gave O’Sullivan time to escape by getting into a bog. This was the last battle or skirmish that took place in Cromwell’s wars. Some time after this O’Sullivan More was obliged to submit, having no conditions but a protection for the families in Dunkerrin, who remained subject to him, and a pass for such of his family who were willing to go to France.’ See notes on O’Sullivan at this link: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/O'Sullivan-2445