I am an old man, sitting under my apple tree. Friends come to see me and get me to talk. They wheedle tales of the past out of me and press me to write them down … I capitulate and desert the apple tree for the desk to write the autobiography which will put an era on ice. But the words will not come. – Hostage to Fortune

Jeremiah Joseph O’Connor, athlete, cyclist, weight thrower, artist, inventor, farmer, publican, writer and ‘professor of everything’ during his teaching career at St Brendan’s College, Killarney, was born in Warley, Essex, on 25 September 1877, one of ten children of Sergeant-Major Daniel O’Connor of Knock Maol, Listowel, and of Her Majesty’s 10th Light Infantry, and Elizabeth Wilmot.[1]

He received his early education at a primary school in Lincoln. In 1886, after twenty-one years’ service, his father retired and the family went to live with their Wilmot relatives in Church Street, Listowel. Their leave-taking was darkened by the legal murder of an innocent Irishman ‘almost of our doorstep.’[2]

Their new Kerry home in Church Street, Listowel was situated by the high wall of Lord Listowel’s demesne of Gurtinard:

Beyond that wall lay forbidden territory. Woe betide the commoner who dared climb the stone barrier to have a peep at the Great House when the family was in residence during the off-season in London. Nothing less than a month in Tralee gaol would purge his transgression.[3]

In 1890, Daniel O’Connor secured a job on the new Lartigue Railway and the family went to live in Dingle.[4] Jeremiah studied at Dingle Christian Brothers School, and was a good student. He was one of five selected for the Intermediate Exam.[5]

In 1894, he won a prize in Classics. He came to the attention of the local Church of Ireland rector, Rev George Basil Anderson. A Sizarship in Greek and Gaelic at Trinity College was mentioned – ‘With a degree from Trinity you can go anywhere in the Empire and hold your head high.’[6] His mother, however, was enraged when she learned about the proposal, regarding it as an act of proselytization. ‘Her fierce outburst against genial, kindly Mr Anderson spurred me to my first overt resistance to her authority.’[7]

Resistance was futile. His mother decided Jeremiah was for the priesthood, and a week of consultations followed:

And so it happened that instead of setting out for Trinity College to win my passport to the higher strata of the British Empire, as Mr Anderson had planned, I took the train to Killarney on the first stage of my journey to the priesthood my mother had ordained for me.[8]

Jeremiah subsequently studied for the Concursus Examination to gain admission to Maynooth College. When his clerical clothes arrived from Tralee, his mother wanted him to flaunt them outside:

I kicked against it and stuck to my well-worn civvies … she begged me to wear the soutane and surplice about the house to assure her that her dream of having a priest in the family was no longer a dream, but an accomplished fact. No. I refused to put them on … I felt that to wear them committed me finally and definitely to the clerical life to which I had no positive leaning beyond that imposed on me.[9]

He entered the college on 8 September 1895.[10] He suffered night sweats when he learned his room was next door to the Haunted Rooms:

The dread legend over the little altar ran through my dreams for the first month, until nature asserted itself and gave me back the unbroken sleep of the healthy animal I then was. I was comforted by the fact that two of my diocesan friends, Frank Crowley and Simon Prendiville, were located in the same eerie corner.[11]

After three years in the college, with strong misgivings about his vocation, he had ‘a showdown with his conscience’ and abandoned his studies in 1898:

One night I left the privacy of my lovely room and went upstairs to Doctor Gilmartin, placed my whole case before him and told him of my desire to leave the college with a clean record … I was up with the lark in the morning, waiting for the porter … I had a last look round the room and into the desk to see that I was leaving everything shipshape, and had removed every trace or sign of my having ever been there.[12]

He taught for a while at Sullivan’s Quay Monastery School before taking up a teaching post at St Brendan’s, Killarney.[13] He began on 25 September 1898, the same year in which his father died from pneumonia.[14] In his memoir, he provides a colourful example on his nineteenth century style discipline when a student declined to carry out a task assigned to him:

Big as he was I was bigger, three years older and a trained thrower of heavy weights in open contests. I caught him by the slack of the pants and the back of the neck, swung him out of his seat and out the large open window behind him, in one mad sweep. He landed on the grass outside and stayed where he fell.[15]

In 1904, science and art were added to the curriculum, and Jeremiah was sent to study in the Metropolitan School of Art in Kildare Street, Dublin.[16] By now he was a married man, having wed Catherine Riordan in 1900.[17]

Lord Kenmare could transport you to Botany Bay or save you from the gallows with a waggle of his little finger

Jeremiah was a fluent Irish speaker, an enthusiastic promoter of the Gaelic League, and a founder member of the Killarney Branch. As well as teaching, he kept a public house at 47 High Street, Killarney for about three years over the door of which he had painted an Irish version of his name.[18]

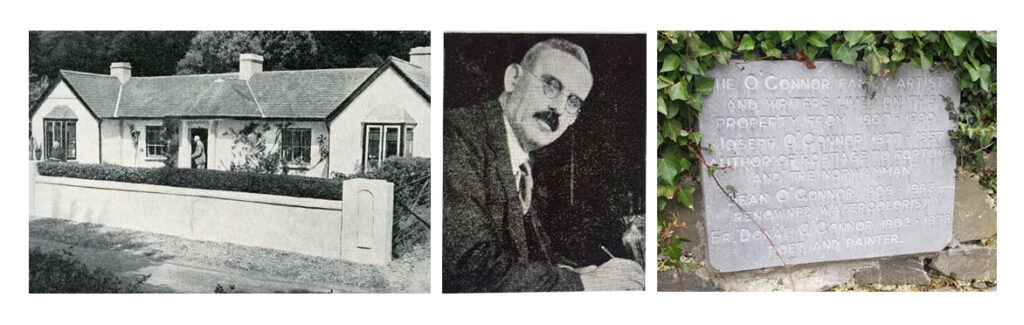

Many Gaelic speakers frequented his establishment, ‘poor in pocket but rich as Damer in poetry and pride of race. They lived so much in the past that they made a bad job of living in the present.’ They included Michael Warren who was educated in a hedge school in the heart of Slieve Luachra.[19]

A fire in a nearby premises caused the family to seek accommodation elsewhere. He found a residence in Fossa on an unused farm held by Major McGillicuddy from Lord Kenmare. The family moved into their new home in 1907.[20] Their neighbour was the infamous land agent, Samuel Murray Hussey, then living out his old age in the Headley mansion, Aghadoe House. He was ‘the despot in the big house … a dominating repellent brute.’[21]

Jeremiah had an association with the Earls of Kenmare for he taught English to the young Dermot Browne, ‘a grand kid, full of surprises and keen as mustard’ who played various pranks on him:

He was lying in wait for me at the door when I turned up at four o’clock next evening for the first lesson. He romped around me like a friendly terrier and led me to the schoolroom in an Indian dance.[22]

Jeremiah also relates a tale about Lady O’Connell of Lakeview, niece-in-law to the Liberator, and her efforts to shorten the sermon of the local parish priest, Father Shine.[23]

In 1922, the new Free State began to replace the mainly English school inspectors with Irish ones, and Jeremiah became one of the first group of inspectors recruited by the government.

I became one of The Twelve Apostles, the twelve inspectors who were selected to supervise the gradual Gaelicising of the national schools under the new dispensation. It was an inspiring assignment. The Twelve spread the light with enthusiasm and there was nary an Iscariot among them.[24]

In 1939, he visited Knocknabro School, situated in the Clydagh Valley where he met Mrs Margaret Lynch, whose own children composed most of the class.[25]

When Jeremiah reached the age of retirement, a bout of ill health caused him to start writing. He contributed to journals and periodicals, including An Claidheamh Soluis and An Lochrann, and was one of the founders of Cualact Bhreannain. He contributed material to An Gúm, including a textbook on art with 200 illustrations in line and colour.[26]

In 1949, he published a novel, The Norwayman (1949) followed by his memoir, Hostage to Fortune, in 1951.[27]

Jeremiah Joseph O’Connor died at his residence in Fossa, Killarney on 2 September 1957. He was buried in Muckross Abbey.[28]

__________________

[1] His father’s background is given on pp16-17 of Hostage to Fortune (1951). His family was evicted from Knock Maol by Lord Listowel in January 1863Siblings mentioned in the memoir are Donal, Eamon, Jack, Vincent, Maudie, Tessie, Lizzie and Addie. Some genealogical detail below. Donal O’Connor, Secretary and Organiser of the Tralee branch of the Gaelic League, selected by Coiste Gnotha under Douglas Hyde to act in the 1912 delegation of the league to the USA in company with Thomas Ashe, Fionan MacColuim, and Fr O’Flanagan. He later lived in America, at Central Park West 25, New York and died there in February 1942. Gerald O’Connor, Manager of IAWS (Irish Agricultural and Wholesale Society) Limerick, who died on 17 January 1962 at Riverside, Barrington’s Pier, Limerick, and was buried at Rath Cemetery, Tralee (his wife Margaret died at her residence, 2 Moyola Terrace, Ennis Road, Limerick on 21 May 1959 and was buried at Rath Cemetery, Tralee). Vincent L O’Connor, Schools Inspector in Chicago. Eamon O’Connor, newsagent and stationer in Ashe Street, Tralee, who died on 4 October 1952. Mrs Agnes Gilligan who died at her residence, Peter’s Cell, St Mary’s, Limerick in February 1951 was a daughter of Daniel O’Connor. [2] Hostage to Fortune (1951), pp20-21. A feud between a gang of Mayo harvesters and Lincolnshire farmhands wound up in the death of one of the locals. ‘The Mayo foreman, an old man whose name I dimly remember as Pat Flattery, was arrested and tried for the murder. Though neither he nor his gang could speak competent English, he was condemned to death and hanged in Lincoln Jail by a Lincolnshire man, Marwood … It was a black day for the small Irish colony who lived in the shadow of the great English cathedral.’ The case, known as The Lincolnshire Murder, was heard at the Lincoln Assizes on Tuesday 17 April 1883. Forty-year-old Thomas Garry, alias ‘Irish Joe,’ was charged with the murder of John Newton, a 74-year-old farmer of Great Hale Fen, Lincs, on 2 February 1883. Garry had lived with Newton for some time, and they often quarrelled. Newton was found shot with his throat cut and Garry was apprehended. He said, ‘I suppose you want me for that job. I shall have to be tried for it and I suppose Marwood will swing me.’ He was executed by William Marwood in Lincoln Prison on 7 May 1883, being attended by RC priest, Rev Canon Croft. Reporters were not admitted. A list of executions carried out in Lincoln Jail between 1883 and 1903 is given in the Lincolnshire Echo, 10 March 1903. [3] Ibid, p34. O’Connor describes (pp35-36) an occasion when his grandfather approached Brindsley Fitzgerald, Lord Listowel’s agent, about cutting down a dying tree near his house to avoid damage to the surrounding buildings. Permission was refused, and the following year the tree fell crushing his grandfather’s piggery and killing the pig. O’Connor also gives his own tale about a tree on his land at Fossa which obscured the view of Eileen Hussey, an unmarried daughter of Sam Hussey ‘more aptly spelled with a small h.’ In a discourse on landlords of 1890, O’Connor describes Lord Ventry as ‘a remote deity’ (p51) and writes, ‘There are no landlords in Ireland now – my grandfather’s dream of an Ireland free from The Incubus has come true’ (p2). [4] See Hostage to Fortune, pp40-41 for the opening of the Lartigue. Daniel O’Connor rented the old bridewell for six months followed by a coastguard’s house in Cooleen. [5] Hostage to Fortune, pp56-68. O’Connor recalls how during one of his classes there the teacher took out a gun to shoot a rook (p55). He pays tribute to his tutor, Brother O’Dowd, and also gives a long chapter to the Dingle Regatta. [6] Ibid, p93. [7] Ibid, p94. ‘The budding classicist was quickly propelled into a free place in St Brendan’s, rescued from the jaws of Protestant TCD’ (Kerryman, 26 May 2000). [8] Ibid, pp95-96. His mother’s ‘attempt to raise the family status by propelling me into the priesthood, failed for lack of the internal impulse in me towards the sacred ministry. It met with ill-luck all along the line – I was only a bare three weeks in St Brendan’s when the sewers went wrong and the manhole under the dormitory in which I slept had to be opened and cleaned. Jimmy North, who cleaned the filthy mess, and I, who slept over it, caught typhoid fever and were shifted off to the Fever Hospital. Poor Jimmy died and I survived a long fight which lasted, counting illness in hospital and convalescence at home, until the following Easter. When I returned to the Seminary I had just two months to prepare for the Senior Grade public examination and for the Concursus, as the diocesan entrance examination to the great ecclesiastical college at Maynooth was called.’ O’Connor was examined for the Concursus by Fr David O’Leary and the Archdeacon of Castleisland, nicknamed ‘Whiskers O’Leary.’ [9] Ibid, p101. [10] In Hostage to Fortune, the author describes his journey to Maynooth with Michael O’Brien, later the Bishop of Kerry, and their first experience of alcohol (pp101-105). Pages 105-139 give account of his college experiences. [11] ‘Crambe Repetita,’ Vexilla Regis (1951), pp49-57. ‘It is, of course, a pure coincidence that none of the three of us finished the arduous path to holy orders.’ The haunted room is also mentioned in Hostage to Fortune (pp105-139). [12] Ibid, pp54-55. Forty years later he returned to his room during a trip to Dublin: ‘I climbed the echoing stairs to my old room next to the Haunted Room, and said a prayer for those who had met sudden and unprovided death.’ In ‘The Last Green Bottle,’ Vexilla Regis (1954-55) pp37-41, O’Connor reflects on his friends from college days. The article carries an image of what may have been his home at Fossa. [13] His companions at that time included Maurice Griffin, one of the founders of The Kerryman. [14] Daniel O’Connor died at his residence, Strand Street, Dingle on 30 March 1898 aged 56. He was interred at St Mary’s Cemetery, Dingle. [15] Hostage to Fortune,(1951) p164. [16] Richard Henry Albert Willis (1853-1905), artist, was then head of the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin. A family mostly connected to the ascendancy families of Kerry, their first child was named Oscar Diarmuid Mac Carthaigh Mac Uileas (1903-1969). R H A Willis ARCA, one time head of the Manchester School of Art, died from heart failure during a holiday at Ballinskelligs, Co Kerry, at the home of his maternal relatives, on 15 August 1905. He was buried in Rathcormac, Co Cork. See obituary, Freeman’s Journal, 23 August 1905. He was married to sculptress Jane Twiss, daughter of George Twiss of Steelroe, Co Kerry, in 1901. For genealogy refer to http://www.odonohoearchive.com/john-twiss-of-castleisland-family-links-to-the-new-world/ Both were members of the Killarney branch of the Gaelic League. Hostage to Fortune, pp154-162, record O’Connor’s period at the School of Art. [17] The couple had four children: Domnall O’Connor, parish priest of Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs; Norah O’Connor; artist Sean O’Connor; and Annie O’Connor. A tribute to J J O’Connor, and three of his children, Donal (1902-1978), Sean (1909-1992) and Ann (1910-1994) is given in ‘The O’Connors of Fossa’ by Catriona O’Connor and Chris Nolan, Fossa & Aghadoe – Our History & Heritage (2007), pp370-377. [18] Hostage to Fortune, pages 173-179. [19] Hostage to Fortune, pp168-169. Warren worked as a gauger, farmer, shopkeeper, and builder of roads. He laid the water mains in the streets of Killarney where manholes bore his name. He lost money in all of his jobs, and ended up in a dark cabin in a back lane ‘still cherishing the manuscripts he had clung to through all his vicissitudes.’ O’Connor also writes (pp187-188) about the extinction of The O’Donoghue, The O’Mahony and The O’Sullivan More from the scenes they dominated in Kerry. [20] Ibid, p191. The property was demolished some years ago and a new property built in the vicinity. An image of Fossa Na Féile, which may have been O’Connor’s home at Fossa, appears in ‘The Last Green Bottle,’ Vexilla Regis (1954-55) pp37. It is worth noting a property styled ‘Fossa House’ on the later OS map which has been demolished. It was extant at the time of the first OS survey. A plaque has been erected on a wall near where the house once stood (next door to The Golden Nugget Bar and Restaurant) inscribed as follows: The O’Connor Family, Artists/And Writers Lived on this/Property from 1907-1990/Joseph O’Connor 1877-1957/Author of “Hostage to Fortune”/And “The Norwayman”/Sean O’Connor 1909-1992/Renowned Watercolorist/Fr Donal O’Connor 1902-1978/Poet and Painter.CDH Ref IE CDH 97. The death of Sean O’Connor occurred at his residence, Muckross Grove, Killarney on 15 July 1992. He left a widow, Eileen, daughters, Catriona and Nessa, and grandchildren. See Evening Herald, 16 July 1992. Fr Donal O’Connor returned from Longton, Stoke on Trent, to the parish of Fossa circa 1963 and died on 7 May 1978. See Kerryman, 12 May 1978. [21] Ibid, pp225-226. It seems a nose injury in his youth caused Hussey’s aspect to change from male strength to orgrish power, ‘the very sight of him subdued the boldest tenant.’ [22] Ibid, pp203-207. ‘Dermot grew up to six feet of radiant masculinity,’ recalls O’Connor, ‘joined a regiment of Guards and paid his scot of the cost of empire with his young life in the retreat from the Mons.’ [23] Hostage to Fortune, pp210-212. Patrick Shine, grandnephew of Fr Bartholomew Shine, OP, parish priest of Brosna, was born in Freemount, Co Cork and educated at Maynooth. He was ordained in 1846, and served Fossa 1857-1892. He died in Castleisland at the home of his sister, Mrs Ellen Horan, on 15 June 1893: ‘The death took place on Wednesday of the Rev Father Shine, PP, of Fossa for a period of more than thirty years. Some time ago owing to failing health the deceased rev gentleman resigned and went to live with some relatives near Castleisland. His impaired health however continued to decline and on Wednesday last he yielded up his spirit at the grand old age of eighty years. Solemn requiem High Mass for the repose of his soul was celebrated at the Parish Church, Castleisland, at ten o’clock on Friday morning after which the interment took place’ (Kerry Sentinel 17 June 1893). In his memoir, O’Connor writes, ‘When he died his relatives came forty miles to take his tired bones home and bury them among the Shines on a quiet hillside overlooking the fat lands of Castleisland. ‘Ye can’t have ‘em,’ they told the parishioners who wanted to keep the good man’s remains in Fossa. ‘Ye starved him while ye had him. We’ll give him what he was used to, before ever he laid eyes on yer hungry lakes and fells. We’ll give him the full of his two eyes of milch cows and fat bullocks, until Gabriel blows his horn.’ [24] ‘The Last Green Bottle,’ Vexilla Regis (1954-55), p39. O’Connor retired from this position in 1941. An account of his role as inspector of schools is given in chapter 29 of Hostage to Fortune (1951). He recalls the occasion when three English inspectors, ‘Rich’, Mr Small and Mr Lethbridge first attended St Brendan’s, and his reaction to Mr Lethbridge’s comment on his methodology in front of his students. ‘The newborn spirit of the Gaelic League was stirring in my breast,’ he wrote, before describing how he dealt with this ‘English imposter.’ The author describes the death of Paddy Ahern of Glencar during the Civil War in Hostage to Fortune, pp216-224. He also discusses at some length a chance meeting with Garda Superintendent Leo Dillon in 1925, who was soon after implicated in the murder of prostitute ‘Honour Bright’ (Lizzie O’Neill). [25] Hostage to Fortune (1951), chapter 30. In this chapter the author discusses the Suggestion Book, an 18 x 12 volume containing the feedback of the inspectors’ visits over the years. See also chapter 32, the penultimate chapter, which deals with ‘the special’ (individual cases brought before the inspectors for a multitude of reasons) and is, in effect, a remarkable tribute to Jane Sullivan, née Donovan, a native of Piper’s Hill, Rosscarbery, and survivor of the RMS Lusitania which was sunk by a German U-Boat off the southern coast of Ireland on 7 May 1915. Knocknabro School House was built in 1909 and closed in 1967. It has been converted into a three bedroomed cottage and was up for sale in 2022. See article by Trish Dromey in the Irish Times, 15 July 2022. [26] Hostage to Fortune (1951), p290. His submission was made in November 1942. In November 1950 An Gúm still held his manuscript ‘against all my efforts to exhume it,’ and another on the Italian Masters. [27] His book was the first publication issued by Michael F Moynihan Publishing Company, Dublin (The Kerryman issued a reprint in 1986 which was launched at Writers’ Week Listowel in that year). Tom MacReevey, Director of the National Gallery, hailed it ‘one of the great books of modern Ireland. It is the great book of modern Kerry.’ [28] He was described in an obituary as a man with ‘a prodigious memory, a great sense of humour, a gifted pen and a deep love of Ireland’ (Tipperary Star, 7 September 1957). In Memoriam – Joseph O'Connor 1877-1957 by Father Senan, OFM, Cap (1957), is a two page obituary extracted from Vexilla Regis, 1957.